![]()

Chapter 1

_______

Theaters of Hospitality: The Forms and Uses of Private Landscapes and Public Gardens

JOHN DIXON HUNT

One of the central issues of eighteenth-century English garden history is how we might situate within our habitual narratives the phenomenon of Vauxhall Gardens (and indeed other so-called public pleasure grounds in London and the provinces). A cluster of more specific issues emerges in the process of answering the general questions: how did the idea of what Horace Walpole called “gardenhood” undergo changes when private designs were transferred into the public sphere? Did its sceneries and other representations—of “countryside,” for example—require modifications as a result not only of changing taste but also of the different contexts in which they were exhibited? Did some of the assumptions and expectations of private-garden experience and reception transfer readily to public places like Vauxhall, and how did its distinctive theatrical character affect them? And, perhaps most interesting, how may we best register Vauxhall’s particular identity as a British site, not least when late eighteenth-century landscape fashions were being touted as essentially new, modern, and above all “English”?

Gardens as Theater and Sites of Hospitality

Sir Henry Wotton, in his 1624 book, The Elements of Architecture, wrote that a gentleman’s house and garden constituted a “Theater of his Hospitality, the Seate of Self-fruition, the Comfortablest part of his own life . . . an epitome of the whole World.”1 We may construe the phrase “theater of . . . hospitality” as indicating how a country estate both offered a collection or compendium (a “theater”) of hospitable features and itself conspicuously performed hospitality, providing a stage where giving and receiving of hospitality were visible and, if well done, applauded.2 Wotton expresses largely traditional assumptions about the responsibilities and opportunities of the landed classes but ones that assumed special significance in the English sociopolitical context; he assumed that such obligations, well performed, guaranteed not only personal satisfaction and fulfillment but also civic and patriotic virtue.

When certain elements of country estates were borrowed for consumption in public pleasure grounds, the theatrical possibilities still existed—visitors at Vauxhall and Ranelagh both acting in and spectating a range of entertainments.3 But the performance of hospitality would be different, not least because it was played out against somewhat exotic and self-conscious scenery but also because the roles of both host and guest are radically challenged, along with the modes of their “self-fruition.” The host was now variously the garden proprietors or their agents (who nonetheless collected entrance fees and money for refreshments provided), sometimes owners of the land (Vauxhall was royal property, so the attendance of the Prince of Wales may well have provided some visitors with the wholly gratifying sense of enjoying royal hospitality), or the very crowds themselves, many of whom had no estates of their own in which to play host. As early as the 1710s, Joseph Addison had glanced at these new possibilities in landscape experience when he mused upon the “greater satisfaction” that somebody might take in “the prospect of fields and meadows” than he or she might in the actual possession of such land itself.4

There were 1,500 people at Vauxhall in June 1736 when Horace Walpole visited; on another occasion he estimated “above five-and-twenty hundred people,” and he assumed (wrongly, of course) that its “vogue” would not last long.5 That these crowds saw themselves as both hosts and guests interchangeably (as well as actors and spectators) is clear from Walpole’s own enthusiastic reports of frequenting in the 1740s the “immense amphitheatre with balconies full of little ale-houses” at Ranelagh or, as his enthusiasm for Ranelagh waned, in joining a “party of pleasure” bound for Vauxhall, hosted by Lady Caroline Petersham in June 1750.6 He described this excursion as some military exercise—after “drumming up the whole town” and assembling a company, they paraded “for some time” up the river and disembarked at the gardens. The vivacity of their party was much increased by a quarrel or fracas that erupted after their arrival—not the first or last to disturb the peace there. The metaphor changes once the group has settled into their booth, preparing their own minced chicken and cherries and strawberries; now the group’s performance is admired by other visitors: “The whole air of our party was sufficient . . . to take up the whole attention of the garden.”

The “Country” as Setting for Hospitality

But that was in 1750. Much earlier the New Spring Gardens, before Jonathan Tyers took over the lease in 1728, was valued for its country atmosphere, an effect that over the years had to be more and more vigorously contrived, with the result that the place would come to please less those who really knew and had opportunities to visit the countryside and enthral those who did not or who wanted something rather different than rural bromides.7 We might apply here what I call the “nightingale” test: Jonathan Swift went to the gardens because of the nightingales’ song; Addison’s Sir Roger de Coverly wished there had been more nightingales and fewer strumpets, but otherwise it “put him in mind of a little coppice by his house in the country, which his Chaplain used to call an Aviary of Nightingales”; by mid-century the management positioned men in the dense shrubberies to imitate nightingales, presumably because that’s what clients wanted to hear and the birds themselves had fled the “motley crowds”;8 by 1769 Horace Walpole advised his foreign guests that this fabled birdsong could be heard only at his Strawberry Hill and not when they arrived at Vauxhall.9 On yet another occasion he told Mme. du Deffand that if she wished to hear nightingales she’d have to travel far from town and not hear remarks about either Wilkes or Vauxhall.10

We have, unfortunately, no visual documents of the New Spring Gardens. But John Evelyn, no mean commentator on gardens, described it as a “pretty contriv’d plantation,” which implies a pleasantly organized ground of shrubs and trees, perhaps subdivided into different planting areas, a layout that is confirmed by the Frenchman Balthazar Monconys in 1663, who found there “a large number of squares, 20 or 30 paces across, enclosed with gooseberry bushes; and all these square plots are planted with raspberries, rose bushes . . . and with vegetables like peas, beans, asparagus, strawberries etc.”; on 23 April 1688 Samuel Pepys watched “citizens” eating the cherries off the trees.

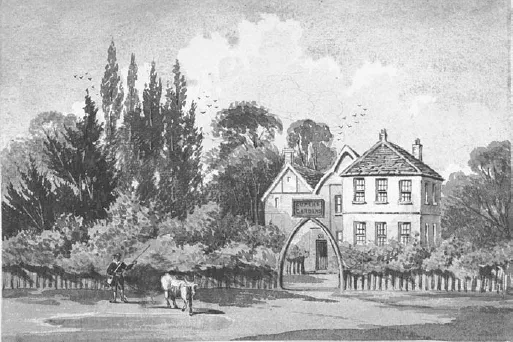

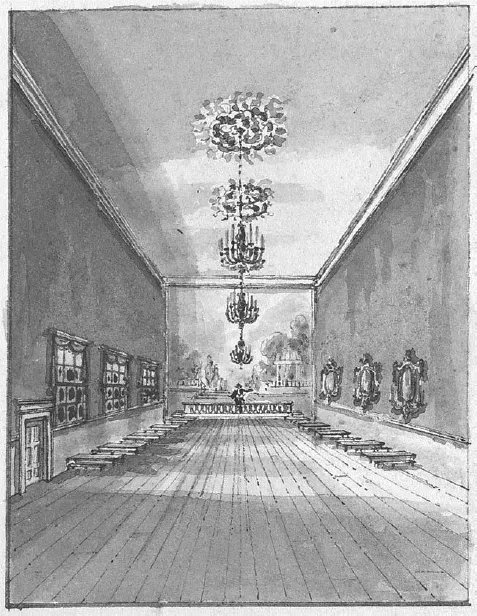

That all suggests how these Spring Gardens in Lambeth initially enjoyed the appearance of a prosperous and productive rural property, already no doubt somewhat factitious but thriving on the complicit acceptance by city visitors of its being the genuine, or real, thing. Restoration comedies confirm this sense of a constructed but highly appreciated country-ness in resorts like Vauxhall; if people wanted to play at being in the country, this was a plausible stage on which to do so.11 Especially after Tyers finally purchased the property in the 1750s, its “rurality” and “gardenness” depended increasingly on a careful match of its much developed physical conditions with the expectations its visitors brought to it. Some, indeed, did not find it country-like at all: “’Tis not the country, you must own; / ’Tis only London out of town.”12 But others sang of “groves,” “glades,” “green-wood,” an Eden without snakes lurking in the grass, an Arcadia, and an example of “rural art.”13 Yet it was not so much that Vauxhall would lose its rural appeal as that it responded to more and more sophisticated ideas of what city folks would expect of a country retreat: its music adopted a distinctly pastoral message; its paintings, too, increasingly promoted an imagery of imagined but somewhat rosy country pleasures like Hayman’s Blind Man’s Buff, artlessly imagining rural pursuits and pastimes. Other public resorts in and around London maintained their distinctive rural air longer than Vauxhall (Figure 1.1), partly because they were smaller; partly because they were less capable of expensive refurbishments; and (one suspects) partly because, in the face of Vauxhall’s relentless show-business, to maintain a rural ambience was strategic and shrewd. Especially the tea gardens in and around London, to which Vauxhall was compared before Tyers took it over, were created around gardens, orchards, and other open-air amenities, like the Pancras Wells, Bagnigge Wells adjacent to Hyde Park, or the London Spa.14 Yet even some of these, without any extensive exterior facilities, sought to project a country air even as late as the 1790s—the Apollo music room, even called a “Petit Vauxhall,” boasted a painted country scene (Figure 1.2) behind which the orchestra of seventy musicians was concealed.

Scenery in the London Pleasure Grounds

By the time we have visual records of Vauxhall in the late 1730s and early 1740s, Evelyn’s and Monconys’s descriptions of a rural and somewhat utilitarian country garden no longer seem so apt. The “large number of squares” is still there, at least in the further reaches and sides of the site, but the emphasis—in both graphic and verbal reports—is now upon the walks, both straight and meandering, some of which are graveled, others grassed. (As I shall suggest later, these could be construed as either perfectly familiar features of English gardens or the accustomed layout of urban promenades, an already well-established European phenomenon.) There were also groves of trees, lawns, a scattering of sculptures and pavilions or fabriques, other insertions like triumphal arches, a Gothic obelisk, a cascade, and “vistas” into the surrounding countryside. The surroundings of Vauxhall were indeed still rural and indicated as such in the post-1751 engraving by J. S. Muller after Samuel Wale (see Figure 1.4). The northernmost edge of the site was a representation of “Rural Downs,” with turf interspersed with fir trees, cypresses and cedars, and a statue by Roubiliac of John Milton on a hillock. But other admired views were contrived by paintings on large canvases, and later fabriques like the Hermitage and Smuggler’s cave were no more than stage scenery constructed of lathe and painted canvas. Some of these insertions were changed over the years, perhaps in an effort to meet either the expectations of “nature” in a garden or a fashion for the exotic: by 1762, for example, a new one showed a “view in a Chinese garden,” which perhaps addressed both. But one thing remained stable: The theatricality of these public grounds, as of private ones, resided in more than the fact of their scenery; as in actual theaters, so here, there needed to be a complicity between the creators/performers and the audience/visitors to use their imaginations to make surroundings that are palpably inadequate into something with the power of the real.15 Not everybody had such imagination; some who disliked the whole business of theater wouldn’t suspend their disbelief, but many Vauxhall-goers did.

Figure 1.1. Entrance to Cuper’s Gardens, Lambeth (c. 1820), pen and ink with watercolor over pencil. Guildhall Library, City of London.

Figure 1.2. Orchestra Room of the Apollo Gardens (c. 1820), brush and ink with watercolor. Guildhall Museum, City of London.

Now all of that design repertoire would have been perfectly familiar to those with some experience of gardens elsewhere in the years before 1750. It may not match our habitual history of English landscapes becoming more and more natural, but in fact it almost certainly approximated the expectations of a “garden” for the majority of visitors. The much commented on walks at Vauxhall, for instance, have their parallels elsewhere: the larger ones, well illuminated, were contrasted with the dark walks in which couples could lose themselves (in more ways than one); as early as 1700 we hear that the “windings and turnings” at New Spring Gardens are “so intricate” that they provided fruitful scope for escapades, a use also confirmed by Restoration comedies.16 By 1718 the incorporation in landscape designs of what Stephen Switzer called “private and natural turns” within more regular garden spaces was commonplace; in Wray Wood at Castle Howard Switzer admired the “intricate Mazes” of Nature’s “much more Natural and ...