![]()

PART I

An Emerging Evangelical Left

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Carl Henry and Neo-Evangelical

Social Engagement

There is no room here for a gospel that is indifferent to the needs of the total man nor of the global man.

—Carl Henry in The Uneasy Conscience of

Modern Fundamentalism

Evangelicals reemerged in the mainstream political consciousness in the year of the nation’s bicentennial. With the 1976 election of Jimmy Carter, himself a born-again Christian, evangelicals had captured the White House. At the time, more than 50 million Americans claimed to be born again. Major news magazines ran cover stories on the recent surge in evangelical political and cultural power. Newsweek even dubbed 1976 the “year of the evangelical.” Evangelist Dave Breese told the national gathering of the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), “It no longer fits to picture us as redneck preachers pounding the pulpit. Evangelical Christianity has become the greatest show on earth. Twenty to forty years ago it was on the edge of things. Now it has moved to the center.” Future presidential candidate John B. Anderson told NAE delegates that “evangelicals had replaced theological liberals as the ‘in’ group among Washington leaders.” Within a few years, the Moral Majority emerged and was instrumental in the election of Ronald Reagan, capping a conservative evangelical ascendancy.1

This image of a forceful evangelical politics stood in stark contrast to its public perception half a century earlier. Not even the most optimistic fundamentalist evangelical in the 1920s would have predicted that the movement would again stand as a significant factor in American life. Indeed, for many decades after the disastrous 1920s, when theological modernists took over mainline denominational structures, fundamentalist evangelical politics was profoundly incoherent. On the populist left, plainfolk evangelicals in southern California supported New Deal policies. Pentecostal laborers, joining the interracial Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, harnessed the democratic potential of evangelicalism against commodity agriculture. On the right, many evangelicals opposed the anti-Prohibition, Catholic presidential candidate Al Smith in 1928 and supported Barry Goldwater’s run for the White House in 1964. On the far right, a handful of conspiratorialist fundamentalists such as Fred Schwartz, Carl McIntire, and Billy James Hargis mobilized in support of a rabid anti-communist agenda. In the middle of the political spectrum, Billy Graham cautiously promoted racial integration in the South as the civil rights movement gained momentum. Featuring a range of political agendas at mid-century, evangelical politics was characterized by uncertainty.2

Evangelical apoliticism, often overshadowed by a much louder (though marginal) far-right fundamentalism, compounded this uncertainty. The Fundamentals, a twelve-volume set of articles published from 1910 to 1915 that repudiated the Protestant modernist movement, warned against getting too caught up in politics, and most fundamentalists generally limited their haphazard political interests to votes for Prohibition and nonactivist sentiments against evolution and communism. Political activism during the 1930s “went into eclipse,” according to historian Mark Noll. From the 1930s to the 1960s, fundamentalist evangelicals devoted much more time to congregational life, holy living, and missionary work than to partisan politics. Those who came to associate with Billy Graham crusades in the 1950s (usually called “new” or “neo” evangelicals to distinguish them from their fundamentalist evangelical cousins) also largely retreated to a quietist stance. They either eschewed social engagement altogether or manifested social conservatism in ways that precluded overt politics. During this period the overwhelming majority of articles in the magazine of the college ministry InterVarsity Christian Fellowship were devoted to topics such as evangelism, hard work and discipline, devotional and inspirational literature, holiness, prayer, Bible-reading, and sexual purity. With significant exceptions, fundamentalist evangelicals did not mobilize on behalf of political candidates nor tie their faith closely to their politics. As late as the 1960s, according to political scientist Lyman A. Kellstedt, data showed that evangelicals were “less likely to be interested in politics, less likely to vote in presidential elections, and less likely to be involved in campaign activities than other religious groups.” Concern for theological orthodoxy and piety subordinated politics, which would emerge finally in the 1970s as a more salient characteristic of evangelicals nationwide.3

No figure embodied the vital shift to political engagement more than Carl Henry, a theologian, editor, and architect of neo-evangelicalism. A leader in many key evangelical institutions—Wheaton College, Fuller Theological Seminary, the National Association of Evangelicals, and Christianity Today—Henry helped drive evangelicalism from its marginal position in the 1930s to the cover of Newsweek magazine in 1976. Significantly, Henry pursued this mission with significant help from the era’s best-known public evangelist, revival preacher Billy Graham. By the 1970s a revitalized evangelical movement, carried along by Henry and Graham, took its place as one of the most important interest groups in postwar America. It was out of this newly engaged movement that the evangelical left would emerge.

I

Carl Ferdinand Howard Henry, born in 1913 as the first of eight children, grew up on Long Island, New York. His nonreligious German immigrant parents, who owned no Bibles and said no prayers before meals, nurtured very little of the evangelical piety their son would practice as an adult. Young Carl played outside on Sunday afternoons, went to vaudeville shows, and served as a sentry for the illicit enterprises of his father, who stole apples from a nearby orchard and sold alcohol from the family farm during Prohibition. The son, however, showed considerably more promise. Taking a job as a reporter for the Islip News, Henry, at age nineteen, became the youngest weekly newspaper editor in the state of New York. Sporting a healthy ambition, a religious skepticism, and an appetite for women and horse racing, Henry was an authentic creation of the roaring twenties.4

An itinerant evangelist dramatically redirected the trajectory of Henry’s life. Following his conversion to evangelical Christianity in 1933, Henry sensed God calling him to a vocation of Christian service. He enrolled at Wheaton College, a school in suburban Chicago that stood at the center of organized neo-evangelicalism. Henry was attracted to the school’s emphasis on thoughtful faith even as he chuckled at its “no-movie, no-dancing, no-card-playing” regulations. Despite the restrictive cultural codes, Wheaton quickly drew the recent convert into the neo-evangelical orbit, filling Henry’s schedule on the energetic and growing campus with study, athletics, chapel, prayer meetings, and theological discussions.5

Henry’s experiences at Wheaton reflected the economic, cultural, and theological ambitions of neo-evangelicalism. Rising prosperity at mid-century sparked a new willingness on the part of apolitical evangelicals to engage broader social spheres. Unable in the 1930s to rely on “old money” as wealthier mainline denominations could, Wheaton’s administrators and its lower-middle-class students like Henry scraped their way through the Great Depression. But in the mid-1940s the college, one of the fastest growing institutions in the nation, embarked on a building binge. It also enjoyed a rapid rise in enrollment as thousands of students and World War II veterans armed with G.I. Bill benefits streamed to the outskirts of Chicago.6

Wheaton’s use of the federal funds points to the critical—and ironic (given many evangelicals’ conservative animus against big government)—role government largesse played in the upward social and economic mobility of neo-evangelicals. Students participated in the Federal Relief Administration work-study program, part of the New Deal legislation of the 1930s. In the 1940s and beyond, G.I. Bill funds paid for tuition, fees, textbooks, and supplies. Others received low-interest loans through the National Defense Education Act. The institution itself received grants from the Atomic Energy Commission and the National Science Foundation. Most important, a favorable tax climate nearly eliminated estate taxes on donations to nonprofit organizations, exempted private colleges from nearly all taxes, and offered lower postal rates.7

By the 1960s the boon of government largesse, a growing national economy, and a concomitant rise in its students’ socioeconomic status tripled the size of Wheaton’s student body to nearly 2,000. Other schools—such as Gordon College near Boston; Calvin College in Grand Rapids; Seattle Pacific University in Seattle; Asbury College in Wilmore, Kentucky; Westmont College in Santa Barbara; and dozens of others—also benefited from growing prosperity. The proportion of evangelicals who had been to college tripled between 1960 and 1972. While the level was still below the national average, it was an impressive leap and an indicator of evangelicalism’s rising social status.8

Henry’s Wheaton also reflected neo-evangelicalism’s pursuit of a more ambitious academic program. Under the leadership of James Buswell, Wheaton’s president, and Gordon H. Clark, an influential philosophy professor with a doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania, the college in the 1940s earned regional accreditation, sought and realized more impressive faculty and student credentials, and contemplated a bold cultural agenda. Clark beckoned his students to contemplate a vision in which Christians would “save and rebuild the West” by transforming culture. Stirred by this far more ambitious vision than the sectarian faith of their parents, dozens of Wheaton students pursued degrees from prestigious graduate schools at a rate comparable to the most elite liberal arts schools in the nation. Many of these students, including Henry, who earned a Ph.D. from Boston University just two years before Martin Luther King, Jr., became leaders of a rising neo-evangelicalism.9

Wheaton during Henry’s tenure was translating this growing intellectual rigor into engagement with the wider culture. Henry himself remained connected to the non-evangelical world as a stringer for the Chicago Tribune. By the 1950s his Wheaton classmates participated in the National Student Association and the Model United Nations. Sports teams competed in intercollegiate athletics with state schools. Meanwhile, American society increasingly glimpsed evangelicalism’s new image. In 1949 Billy Graham, the college’s most recognized alumnus, held an eight-week crusade in Los Angeles, during which syndicated newspapers across the nation printed positive coverage. The dynamic young evangelist, the nation soon saw, was not a wild-eyed preacher of dogmatism; he wore a stylish suit and could speak the language of youth culture. Such public attention helped bring evangelicals out of the exile to which they had retreated during the Scopes era. Increasingly, this well-educated, upwardly mobile variety of evangelical aspired to represent all the nation’s many varieties of evangelical Protestants, including quietist holiness adherents, big-tent Pentecostals, Anabaptist pacifists, ethnic confessionalists, and strident fundamentalists.10

Transformations in neo-evangelical theology mirrored—and shaped—this cultural engagement. Specifically, Henry and others began to reject the dispensational premillennial eschatology of their heritage. The end times theory of dispensationalism, a nineteenth-century innovation of British evangelist John Darby, divided history into discrete time periods and argued that Christians would be “raptured,” that is, removed from the earth prior to Jesus Christ’s return and millennial reign. Fundamentalist evangelicals considered the rapture to be imminent. Such a framework emphasized getting the world ready for the rapture, for fear that many might be “left behind.” While at no time did fundamentalists uniformly hold to dispensationalism, many did, and the implications for their social and political action were profound. An all-encompassing concern for saving souls eventually subsumed nineteenth-century evangelical activism on issues such as abolition and women’s suffrage. Dispensationalist eschatology inhibited social action among many fundamentalists.11

But by the 1940s the hold of dispensationalism was beginning to slip in some quarters. At Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California, Henry’s next stop on the expanding neo-evangelical circuit, professors were quietly putting aside premillennial dispensationalism. Henry, for example, always attached the word “broadly” when speaking of his premillennial eschatology. Other inaugural Fuller faculty—including celebrity pastor Harold Ockenga, bibliophile Wilbur Smith, Old Testament scholar Everett Harrison, New Testament scholar George Eldon Ladd, and all-around factotum Harold Lindsell—showed considerable coolness to dispensationalism in the pages of Fuller’s scholarly journal Theology News & Notes. Within decades, antipathy toward dispensationalism had nearly become a litmus test for neo-evangelical orthodoxy. Prospective Fuller faculty had to defend themselves against sympathies for dispensationalism. Though the dismissal of dispensationalism may not have been as unambiguous in other evangelical quarters (in part for fear of offending conservative constituents), there seemed to be a clear correlation between theological change and neo-evangelicals with designs on social engagement. Rejecting the “kingdom later” view of the dispensationalists, some felt compelled to offer whatever measure of temporal justice and mercy they could in a hurting world. Neo-evangelicals were refashioning their image from fundamentalist refugees in a crumbling Babylon to custodial heirs of a Reformation legacy dedicated to ushering in a new Jerusalem in America.12

“Fundamentalism” had become a bad word for many neo-evangelicals. In United Evangelical Action, the magazine of the National Association for Evangelicals, an organization he had helped launch in the early 1940s, Henry wrote that “fundamentalism is considered a summary term for theological pugnaciousness, ecumenic disruptiveness, cultural unprogressiveness, scientific obliviousness, and/or anti-intellectual inexcusableness . . . extreme dispensationalism, pulpit sensationalism, excessive emotionalism, social withdrawal and bawdy church music.” Students at Henry’s alma mater, who recognized this movement away from fundamentalism, were glad to abandon the cultural idiosyncrasies of their tradition. An editorial in the student newspaper Wheaton Record entitled “Farewell to Fundamentalism” read, “I hereby resign [fundamentalists] to their slow, convulsive death in both peace and isolation.” By the 1950s a coterie of neo-evangelical leaders, most of them associated in some way with Wheaton or Fuller, had risen to lead the way from cultural separatism to social engagement. They articulated a more comprehensive evangelical agenda for the twentieth century that proposed increased political, scholarly, and social activity. Henry himself emerged as the preeminent prophet and theologian of the emerging neo-evangelical movement.13

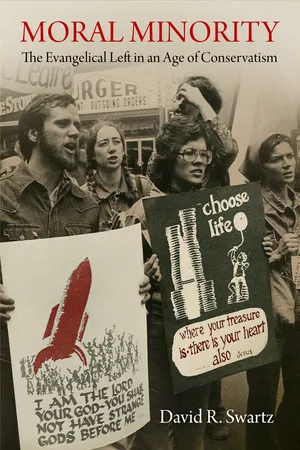

Figure 1. Carl Henry, pictured here in the early 1950s as a faculty member at Fuller Theological Seminary, sought to recover evangelical social engagement. Henry would become the founding editor of the neo-evangelical standard Christianity Today. Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, Wheaton College, Wheaton, Illinois.

II

Still a young scholar at the just-established Fuller Theological Seminary, Henry in 1947 released a movement-defining manifesto that carved out space between the social gospelism of Protestant liberalism and the separatist, socially pessimistic tendencies of fundamentalism. The Uneasy Conscience of Modern Fundamentalism, Henry’s 88-page tract, sharply indicted the “evaporation of fundamentalist humanitarianism.” Its call for social involvement, according to historian Robert Linder, “exploded in the field of evangelical thought . . . like a bombshell.” Modernity, Henry began, was replete with social evils, among them “aggressive warfare, racial hatred and intolerance, liquor traffic, and exploitation of labor or management, whichever it may be.” But fundamentalism, motivated by an animus against religious modernism, had given up on worthy humanitarian efforts. According to Henry, this lack of social passion was a damnable offense. Instead of acknowledging the world-changing potential of the gospel, fundamentalists had narrowed it to a few world-resisting doctrinal and ascetic concerns such as “intoxicating beverages, movies, dancing, card-playing, and smoking.” The redemptive message of Christ, Henry wrote, had implications for all of life, not just the personal.14

Henry also targeted religious liberals with a sharp critique. The liberal social gospel, he argue...