![]()

Chapter 1

“Nature Never Intended Me for Obscurity” The Celebrity

After their Christmas Eve wedding, Elizabeth and Jerome embarked in early 1804 on a honeymoon tour, spending a few weeks in the capital. Seemingly everyone who was anyone in the city wanted to meet the couple whose romance provided material not just for gossips but even for newspapers. Margaret Bayard Smith, the wife of the editor of the powerful National Intelligencer and one of Washington's social leaders, quickly recognized that Elizabeth's husband and, even more significant, her style of dress would make this young woman from Baltimore a celebrity. Bayard Smith even contributed to Elizabeth's growing fame by writing about her daring fashions to friends and family, especially after the sensation Elizabeth created at a winter ball given in her honor and attended by “an elegant and select party” of the Washington elite.1

Elizabeth arrived at the house of her uncle, Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith, wearing a sleeveless, backless, white crepe dress of Parisian design that was, as Rosalie Stier Calvert described it, “so transparent that you could see the color and shape of her thighs, and even more!”2 Elizabeth's thin dress left “uncover'd” “her back, her bosom, part of her waist and her arms.” With no shift or chemise underneath, “the rest of her form” was “visible.” Not surprisingly, her appearance drew public attention, and a “mob of boys” swarmed around her as she entered the house. Once inside, according to Bayard Smith, Elizabeth's “appearance was such that it threw all the company into confusion, and no one dar'd to look at her but by stealth.” Outside, crowds gathered to peer through the unshuttered windows at the “extremely beautiful” and “almost naked woman.”3 Highly offended by Elizabeth's scandalous clothing, “several ladies made a point of leaving the room” and later reprimanded her for the spectacle she had generated, explaining that “if she did not change her manner of dressing, she would never be asked anywhere again.”4 Elizabeth was supposed to attend another soiree the next evening, but her aunt and “several other ladies sent her word, if she wished to meet them there, she must promise to have more clothes on.” The rebuke made Bayard Smith “highly pleased with this becoming spirit in our ladies.”5

But the spectacle Elizabeth created at her uncle's ball also inspired Thomas Law, the wealthy English merchant who had married Martha Washington's granddaughter, to write a few lines of poetry that soon circulated in the elite circles of the capital and its environs. Law's poem—another form of rebuke—was much harsher (and bawdier) than anything a lady could have said with propriety. Interestingly, it condemned not only Elizabeth's clothing and morals but also her lack of republicanism:

I was at Mrs. Smith's last night

And highly gratified my self

Well! What of Madame Bonaparte

Why she's a little whore at heart

Her lustful looks[,] her wanton air

Her limbs revealed[,] her bosom bare

Show her ill suitted for the life

Of a Columbians modest wife

Wisely she's chosen her proper line

She's formed for Jerom's concubine.6

Law, known as “a great poet” in the capital area, gave the lines to Rosalie Stier Calvert while staying at her nearby plantation, Riversdale. His poem circulated locally for a few days after the Smith ball before Aaron Burr “wickedly told” Elizabeth that “someone had written some very pretty verses about her beauty.” Elizabeth naturally “insisted on seeing them.”7 Law hurriedly scribbled a second part to soften what he had first written that ultimately flattered her:

Napoleon full of trouble

Conquers for an empty bubble

Jerom's conquest full of pleasure

Gains him a substantial treasure

The former triumphs to destroy

The latter triumphs to enjoy

The former's prise were little worth

If e'en he vanquished all the earth

The latter Heaven itself has won

For the ador'd Miss Paterson.8

When Calvert sent the poem to her French-speaking family in Belgium, it became an early contribution to Elizabeth's celebrity in Europe. Since the lines were written in English, Calvert directed her mother to “get my brother to read them to you” so that she could “understand all of the humor.”9

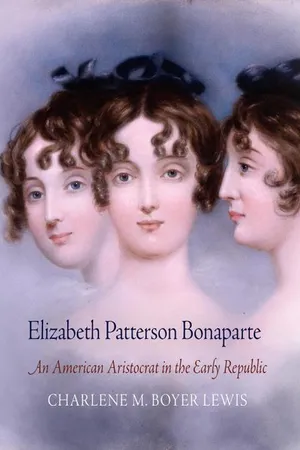

Not all of the public commentary about Elizabeth at this early stage of her celebrity was negative. Thomas Law circulated other odes to her that were much more complimentary in tone than that inspired by Smith's ball. Around the same time as the ball, Jerome and Elizabeth arranged to have the already famous Gilbert Stuart paint a portrait of her to send to France, probably in hopes that Napoleon would accept her after seeing her beauty. Elizabeth's growing celebrity made her portrait a topic of conversation and interest; many made a special trip to Stuart's studio to look at it. Elizabeth's new friend, Sally McKean Yrujo, the Philadelphia wife of the Spanish minister to the United States, viewed the portrait. Many viewers were certainly disappointed that the portrait consisted of three different views of her head—“a full face, two thirds face & a profile”—rather than her full figure. Struck by her beauty, gossips predicted that “upon the portrait's arrival at Paris, the Venus de Medici would be thrown in the Seine.” After gazing at Elizabeth's three visages, Law wrote another poem that Yrujo sent to Elizabeth. Though still sarcastic, this one probably atoned for any hurt feelings the other might have caused.

The painter won't oerwhelm the Sculptor's art

For Venus' Statue we no longer fear,

The matchless form of Mde. Bonaparte

Will not by Stewart at full length appear.

But ah! The picture with three heads in one

With so much fervor idolized will be

I tremble, lest our faith should be undone

By this new captivating Trinity.10

Figure 2. Gilbert Stuart's three-part study of Elizabeth captivated admirers and added to her celebrity. Copy of original, George d'Almaine, 1856. Image #XX.5.78, courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society.

After these few weeks in Washington in 1804, Elizabeth's celebrity status, both nationally and even internationally, was assured. Through letters and gossip, descriptions of Elizabeth's clothes and way of wearing them fanned out across the countryside and even across the Atlantic. To many, her style of dress was unsuitable for the United States. But the sensation Elizabeth created with her marriage, her fashions, and her portrait captivated Americans and made her one of the most famous women in the early republic.

Many Americans, including military leaders and presidents, were famous in the first fifty years of the country's existence, but few were celebrities. In the early national era, fame and celebrity were not synonymous terms, as they have essentially become in our own time. Both fame and celebrity in this era rested on being widely known and publicly praised. But, unlike celebrity, fame in the early national period came through particularly notable public service that highlighted a person's honor and virtue.11 Celebrity implied neither public-mindedness nor virtue. A person gained celebrity through acts that often had nothing to do with public service but everything to do with drawing attention to him-or herself, in other words, with becoming popular. Special talents or an especially attractive appearance could make one a celebrity. Dramatic episodes in one's personal life that became public could transform one into a celebrity; so too could the act of marrying someone famous or, better yet, celebrated. Writing for the public, especially travel accounts and novels, and acting on the stage could make one a celebrity as well. Both fame and celebrity required an admiring audience, but those who sought fame had an eye on posterity, on their historical legacy. Celebrity was more temporary, the cultivation of renown during one's lifetime. But both fame and celebrity could translate into power, though fame's influence often came more in politics and celebrity's in the social and cultural arenas.

Another crucial difference separates the two terms: fame, as defined in the early republic, was almost exclusively open only to men; women found it almost impossible to win fame. Just a few women, such as Martha Washington and Dolley Madison, became famous through glorious deeds of public service. Not coincidentally, they were First Ladies and served as models of female patriotism in war time.12 Fame, and its concern with a future reputation, was primarily a male goal. George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison, for example, all had learned that pursuing fame not only provided an acceptable means for pursuing individual acclaim because of its emphasis on public service but also ensured a historical legacy.13 Women who, despite society's expectations of ladies, also desired influence and acclaim had to seek something other than fame. While the pursuit of fame may have been mostly closed to them, celebrity was left wide open. Ambitious women seized this path to public recognition and social power. Though celebrity was apparently gender-neutral, it may have been especially female in the early nineteenth century.

Men and women gained celebrity in different ways. For men to achieve celebrity, at least before the 1820s, they first needed fame.14 Famous soldiers, politicians, merchants, bankers, and ministers could then achieve celebrity if they had an attractive appearance and a charming personality to match their feats of public service. For example, Commodore Stephen Decatur, a hero of the War of 1812, earned his celebrity status because of his military exploits as well as his dashing good looks and manners. Conversely, while James Madison was certainly famous as a statesman and president, few would have considered him a celebrity. Indeed, Sarah Gales Seaton claimed that the president, “being so low of stature,” was regularly “in imminent danger of being confounded with the plebeian crowd.”15 With professional, political, and martial spheres closed to them, ambitious women found other ways to gain public acclaim by using their beauty, clothes, writings, marriages, or even children, though many of these factors remained linked to men. Decatur's wife, Susan Wheeler, had been celebrated as a belle around Norfolk, Virginia, for her beauty, manners, and conversation while single, but she became a real celebrity only as the wife of a war hero and a widow after her husband's dramatic death in a famous duel.16 In contrast, what ever celebrity James Madison attained came from his wife, whose appearance and behavior, according to Seaton, “distinctly pointed out her station wherever she moved.”17 Because of her stylish ways and vivacious personality, Dolley Madison surpassed renown and achieved national celebrity—a celebrity, however, that ultimately depended on her marriage to James.18

Female celebrity took various forms in this era: great beauty, fashionable clothing, special talents, or bold manners could make a woman a celebrity. It was common in this period, for instance, to speak of “celebrated belles.” In 1807, John Quincy Adams informed his wife, Louisa, that a Miss Keene was renowned in Washington, D.C., for her performance “on the Tambourine, with all the confidence and all the graces of a gypsy”; “her dress,” he continued, “is as much admired as her person and manners.”19 Yet all of female celebrity began at the same point—with a spotless reputation. In America, unlike in Europe, immoral behavior formed an insurmountable barrier to celebrity for women. The gender standards of the time made private virtue, unlike the public virtue expected for fame in men, a precondition of celebrity in women. Immoral behavior gained women infamy and disdain, not approval and acclaim. Since women were not expected to be widely known, those seeking celebrity had to walk a delicate line between behaving in ways that would gain them attention—that could create spectacle—and in ways that would immerse them in scandal. Female celebrities needed to preserve a reputation for upright behavior to stay in the public's favor. The Englishwomen Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Wilkes Hayley (the sister of the radical John Wilkes) both suffered rapid declines in their American celebrity status when “immoral” choices they had made in their personal lives were revealed.20 Women who were celebrated as socialites, writers, or artists were also daughters, wives, or mothers, and were expected to meet the normal expectations for those roles. The stresses of being a celebrity, however, were enormous since such status relied on a whimsical public and a demanding, constant self-presentation. For some, though, the stresses seem to have been justified by the “psychological and social rewards” an exceptional performance could draw.21 Women had few ways to gain confidence, influence, and power. Being a celebrity was just one more role a woman could play, but one with potentially more rewards than any other for an ambitious woman.

Any woman or man who led a public life in the early republic faced the challenge of negotiating between the private and public self or, more accurately, of presenting a public self that was also the natural self. In the small world of the early United States, anyone who cultivated a public persona, whether political or social, did soon a small stage under close scrutiny. This intense gaze made public personalities constantly aware of how they presented themselves, always careful about the performance of their social and political identity. They had to pay constant attention to which particular self they presented at which particular time since their audiences were not always the same. The theatricality of these public performances of identity, however, was to remain unacknowledged; they should appear natural. Late eighteenth-and early nineteenth-century elites expected the public self also to be the sincere and authentic private self.22 But this sincere self was to be a genial and affable one; negative emotions, such as anger or sadness, were to remain hidden. In spite of the strictures on permitted emotions, enlightened men and women expected the performance of one's public identity to be a true one, revealing the natural self, not a disguised self. This expectation that the presented self was the true or natural self created many unhappy men and women who discovered just how false these “authentic” identities could really be.

Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte, one of the nation's first female celebrities, also became one of the best of her day.23 She achieved and cultivated her celebrity with consummate skill and great éclat (and in ways modern Americans would recognize). She embraced a cosmopolitan identity that transformed her into a celebrity. Her beauty, fashions, and manners, as well as her marriage, family connections, and potentially royal son, all ensured her status as one of the leading American celebrities—a role that gained her popular acclaim in the United States as well as in Europe. Like later celebrities, however, Elizabeth's popularity waxed and waned as she garnered both adoration and condemnation. Her resounding success reveals as well that Americans have long been captivated by celebrities. It is not a new phenomenon or even one that required mass media and a mass culture, though the increase in literacy and in the number of newspapers in the early 1800s surely helped. The engravings, poems, articles, and announcements about Elizabeth that appeared in print increased her popularity. At this time, Americans sought cultural leaders just as they did political ones, and they celebrated them and gave them importance. Perhaps not surprisingly, Washington, D.C., provided one of the best arenas for the cultivation of celebrity, and Elizabeth visited regularly. The public identity that Elizabeth cultivated for herself also served a greater social—and national—purpose as she helped set the tone for fashionable culture. Her role as the nation's cosmopolitan celebrity helped define what kind of culture Americans wanted for their republic and, indeed, helped create the American love of celebrities.

Growing up in the 1790s, Elizabeth could have read about young women who sought a place in the public eye, who desired celebrity and were not necessarily condemned for it. In her 1796 play, The Traveller Returned, Judith Sargent Murray allowed her heroine, Harriot Montague, to dream of becoming a “distinguished” woman. Chastising her cousin Emily who wanted to “slide through life … without observation,” Harriot wished she could “be paragraphed in the newspaper” so that her name would be handed “to thousands, who w...