![]()

Chapter 1

Cohabitation

Celtic populations in northern Britain had received Christian conversion by the fifth century, when they began to participate in the conversion of Ireland. During the sixth and seventh centuries, religious traffic across the Irish Sea shifted strongly in the direction of Britain as Irish missionaries came into Scotland and Northumbria. On the island of Iona, 80 miles off the Irish coast and one mile off the Scottish Isle of Mull, Columba (Colum-cille) founded a monastery in 563 that soon became the leading religious foundation of the Irish world. Proselytizing among the Picts and then in the seventh century among the Anglo-Saxons of Northumbria, monks of Iona founded Lindisfarne and Melrose, where Cuthbert was educated beginning in about 651. The influence of Irish tradition persisted in Britain through the later seventh century, alongside the influence of Roman traditions dating from the sixth-century mission sent into England by Pope Gregory the Great.1

Written down between the seventh and ninth centuries, my earliest set of works reflects the contiguity of Irish and northern British monastic life and thought. These works value ascetic simplicity, prayer and study, ecumenical work, and productive interactions with animals. This latter aspect of Irish monasticism is pointed out by scholars but is seldom a subject of analysis.2 Animal relationships in monastic writing are not as favored in scholarship as monastic relationships with secular rulers, the Roman church, and the works of the early church fathers. The Irish and northern British monasteries, however, were deeply enmeshed in nature, reflecting their founders’ ambitions to seek out deserted places and to create new settlements where none had been before. The typical monastic foundation of the earlier centuries was little more than a collection of wattled huts for monastic solitude near a larger structure for communal meals and an oratory or church.3 Wild nature challenged monastic settlements and domesticated nature facilitated their work. An Old Irish lyric about a monastic scholar and his cat and a handful of early Irish saints’ lives will demonstrate how rich medieval thought about animals could be in these ascetic foundations.

The Irish lyric “Pangur Bán” meditates on the symbiosis of a scholar's efforts and a housecat's hunting, to discover within their analogous work a precisely observed equivalence between their minds. In the second half of this chapter, the scene of cohabitation moves from the small space of a scholar's monastic hut to the seas, pasturelands, and wilderness of seventh and eighth-century hagiography. Poised at the leading edge of humanity, saints of the Irish tradition establish their sanctity by entering into relationships with wild and domestic animals, shaping all creation into a more hospitable place for Christian settlements.

Living with animals in the Middle Ages, so intensive and pervasive in contrast to our century's curtailed living contacts, could not yet be conceived in terms of “domestication,” that is, a long process of genetic adaptations toward cross-species tolerance and exploitation. Instead, medieval sources often imagine cohabitation with animals as a heuristic arrangement in the here and now of a particular creature and a particular human. Yet the etymological root of “domestication,” in medieval Latin domesticare, “to dwell in a house” and by metaphoric extension “to accustom, to become familiar with,” connects the contemporary term back to the medieval view that a particular relationship of two beings could exemplify how entire species have come into interdependence with humans.4 Indeed, the Irish texts of this chapter treat the immediate present of a cross-species encounter as paradigmatic for cross-species relationships more generally, contributing a certain universality and explanatory force to the scenes of contact.

Pangur Bán

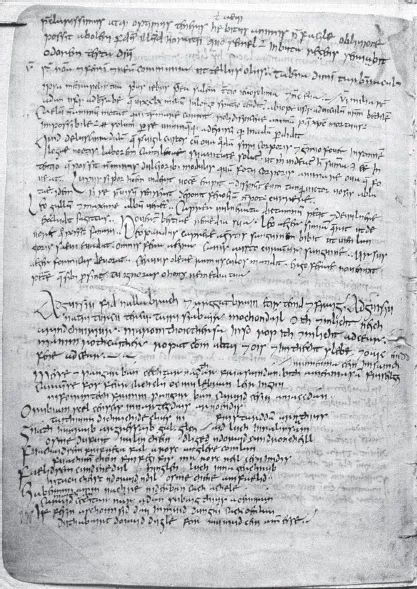

The Old Irish lyric called “Pangur Bán” (“White Fuller”), “The Scholar and His Cat,” or “The Monk and His Cat” has been widely translated, printed, and appreciated over the last century. The lyric survives in a single ninth- century manuscript that was probably produced in Ireland; the lyric's composition may be contemporaneous with its manuscript or somewhat earlier.5 The manuscript's association with the eighth-century abbey at Reichenau in southern Germany testifies to the peregrinations of Irish monks across Britain and Europe. “Pangur Bán” appears in this manuscript, not marginally as is sometimes said, but across the bottom third of folio 1 verso. Seamus Heaney offers the finest poetic rendering of “Pangur Bán”:

Figure 1. “Pangur Bán” in the Reichenau Primer. Carinthia, Austria, Archiv St. Paul 86 b/1, folios iv—2r. By permission of Stift St. Paul. Digital image by Dr. Konrad J. Tristram.

Pangur Bán and I at work,

Adepts, equals, cat and clerk:

His whole instinct is to hunt,

Mine to free the meaning pent.

More than loud acclaim, I love

Books, silence, thought, my alcove.

Happy for me, Pangur Bán

Child-plays round some mouse's den.

Truth to tell, just being here,

Housed alone, housed together,

Adds up to its own reward:

Concentration, stealthy art.

Next thing an unwary mouse

Bares his flank: Pangur pounces.

Next thing lines that held and held

Meaning back begin to yield.

All the while, his round bright eye

Fixes on the wall, while I

Focus my less piercing gaze

On the challenge of the page.

With his unsheathed, perfect nails

Pangur springs, exults and kills.

When the longed-for, difficult

Answers come, I too exult.

So it goes. To each his own.

No vying. No vexation.

Taking pleasure, taking pains

Kindred spirits, veterans.

Day and night, soft purr, soft pad,

Pangur Bán has learned his trade.

Day and night, my own hard work

Solves the cruxes, makes a mark.6

This beautiful poetic translation has certain marks of modernity that appear when we set it next to a rigorously literal translation from Whitley Stokes and John Strachan's anthology of Old Irish poetry:

I and Pangur Bán, each of us two at his special art:

his mind is at hunting (mice), my own mind is in my special craft.

I love to rest—better than any fame—at my booklet with diligent science:

Not envious of me is Pangur Bán: he himself loves his childish art.

When we are—tale without tedium—in our house, we two alone,

we have—unlimited (is) feat-sport—something to which to apply our acuteness.

It is customary at times by feats of valour, that a mouse sticks in his net,

and for me there falls into my net a difficult dictum with hard meaning.

His eye, this glancing full one, he points against the wall-fence:

I myself against the keenness of science point my clear eye, though it is very feeble.

He is joyous with speedy going where a mouse sticks in his sharp claw:

I too am joyous, where I understand a difficult dear question.

Though we are thus always, neither hinders the other:

each of us two likes his art, amuses himself alone.

He himself is master of the work which he does every day:

while I am at my own work, (which is) to bring difficulty to clearness.7

Juxtaposing Heaney's lyric translation with a close paraphrase reveals two revisionary tendencies shared by many recent translators and readers: the ninth-century lyric's vivid depiction of similarity between scholar and cat morphs toward parity and acquires an emotional charge. Heaney's scholar and cat are “equals,” “kindred spirits.” Pangur purrs softly; he is “happy for” the scholar. None of these renderings is accurate to the Irish text, but all seem plausible translations in the context of our era's pet-keeping. “Equals” and “kindred spirits” are interpretive extensions of the lyric's parallel phrasing: in Stokes and Strachan, “his mind … my own mind,” “I love … he himself loves.” Heaney's “soft purr, soft pad” is an outright addition, and his “happy for me” alters the original's “not envious of me,” a fascinating expression that altogether reserves judgment on the cat's orientation to the scholar: does the cat's absence of envy express tolerance or simply obliviousness—relationship or nonrelationship? Heaney's shifts toward fellowship and sentiment are in fine company: W. H. Auden similarly nudges the Irish text to read “how happy we are / Alone together.”8 From the scholarly corner, Jeffrey Jerome Cohen invokes “Pangur Bán” to argue that, like contemporary pet owners, “medieval people loved these same animals with an ardor equal to that which today has encouraged the development of gourmet dog biscuits and Tiffany cat collars.”9

Love does suffuse this lyric with glowing joy, but scholar and cat are depicted loving their separate endeavors, not loving each other. The scholar's relation to the cat is more meditative than affective: Pangur exemplifies for the scholar a deep commitment to “his special art,” “the work which he does every day.” Yet the scholar also values a carefully delineated connection between Pangur and himself. This connection comes into view when we set aside the contemporary assumption that sharing affection is the best of all relationships with other creatures.10 The Irish lyric depicts instead a relationship nearer the medieval ideal of cohabitation, in which each animal in domestic space has a specialized task to perform. Only within the sharply observed specifics of their separate tasks does the scholar assert a small, precisely observed equivalence between them: both are capable of focusing so intently at their work as to produce a kind of elation, a “joyous” state of concentration that they share.

“Unlimited is feat-sport”

To be sure, the “childish art” of hunting mice stands in contrast to the textual labor of the scholar, expressing the fundamental difference between irrational and rational creatures that medieval exegetical tradition grounded in the text of Genesis. As “Adam called all the beasts by their names and all the fowls of the air and all the cattle of the field” (Genesis 2:20), patristic commentary finds a foundational distinction between the rational, speaking first man and all other living creatures. This exegetical tradition, a topic of Chapter 3 on the bestiaries, is no doubt latent in “Pangur Bán.” The difference between catching mice and solving textual cruxes makes “our house” a microcosm of creation's rightful hierarchy.

Anthropomorphic tactics for depicting the cat, however, put certain pressures on the lyric's hierarchical differentiation between scholar and cat. The cat's name, “Pangur Bán,” means “white fuller,” a man who works with fuller's earth and comes to be covered in its pale dust.11 Given the high value of work and craft in the lyric, one might hazard that “white fuller” evokes both the cat's pale fur and his workmanlike behavior. The cat is next anthropomorphized as a net-wielding gladiator or perhaps a huntsman equipped with a net (his extended claws) as he performs “feats of valor.”12 Cat as workman and cat as valiant gladiator have mock-heroic potential that could reflect doubly on the cat, humorously inflating his worth in order to discredit it and distance him from the scholar. In a counterstrategy, however, the scholar shares mock-heroic status with the cat as “there falls into my net a difficult dictum with hard meaning.” Both of them are attempting “feats of valor” that could look small from the net-wielding, death-defying gladiator's perspective. Anthropomorphism can cut in many directions, but in “Pangur Bán” the consistent strategy is to strike analogies that reinforce the scholar's bemused admiration for Pangur with his self-deprecating account of his own efforts to work well. The bodily organ through which both of them work is the eye, crucial for each task. The scholar's “very weak” eye may suffer from presbyopia but is surely metaphoric for his intellectual struggles. Here again the scholar's self-deprecation sets Pangur's workmanship ahead of his own.

The scholar's characterization of Pangur's “special art” interprets a peculiar trait of domestic cats: they do not kill only when they are hungry, in order to eat. Probably as a result of artificial selection for good mousers over centuries of cohabitation with humans, domestic cats (Felis catus) may kill many times a day without eating their prey, as if they were hunting just for the sake of hunting.13 Crooks and Soule call them “recreational hunters.”14 In the moment of Pangur's and the scholar's cohabitation, it appears that a white cat who hunts all day in disconnection from hunger “amuses himself” and “likes his art” in analogy to the scholar's long hours of fascination with textual analysis. Both of them are specialists.

Medieval sources call the domestic cat catus less often than musio, murilegus, sorilegus, and muriceps (mouse catcher, rodent catcher), indicating the quality for which cats were most valued. During the Roman Empire cats were taken northward from the Mediterranean; some of the tiles excavated at the Roman town of Silchester in Britain bear the footprints of cats.15 The Welsh legal code of Hwyel Dda specifies the worth of a cat as follows: “The price of a cat is four pence. Her qualities are to see, to hear, to kill mice, to have her claws whole, to nurse and not devour her kittens. If she be deficient in any one of these qualities, one third of her price must be returned.”16 The noun “Pangur” is not Irish but Welsh, so that Pangur's presence in an Irish lyric, perhaps also in an Irish monastic house, suggests the best mousers may have been worth taking from place to place and even buying and selling. But a monk need not purchase cats; their upkeep amounts to nothing and they reproduce freely even in a feral state. Thus they were characteristic denizens of the poorest households, including those of monks and hermits, where manuscripts as well as food supplies needed protection from rodents.17

As one of so few possessions, the scholar's cat poses a risk to spirituality: one might be tempted to take frivolous pleasure in a cat. John the Deacon's ninth-century Life of St. Gregory tells of a hermit who possessed “nothing in the world except for a cat.” He was so fond of her that “he caressed her often and warmed her in his bosom as his housemate.”18 His virtuous asceticism brought him a dream foretelling that in heaven he would be placed next to Pope Gregory. The hermit questioned whether this place was a just reward for his ascetic life, so different from the Pope's life of luxury. God replies to him in a second dream that he is more wealthy with the cat he cherishes so deeply than was Gregory with all his riches, which he did not love but rather deplored. The anecdote celebrates Gregory's transcendence of worldly ties but also...