![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: Rebordering Europe

We are like travelers navigating an unknown terrain with the help of old maps, drawn at a different time and in response to different needs.

—Seyla Benhabib

The expansion of the European Union on May 1, 2004, to incorporate eight new member states in postsocialist Eastern Europe, and its second act of including an additional two in 2007, have been the latest in the centuries-long sequence of border shifts in Europe.1 Contours of European maps have usually changed in the aftermath of wars. This time, however, the shift was peaceful, and the territorial outlines of the countries involved remained untouched. Instead, their borders were refitted for a new purpose. Where the new members bordered on each other, or on old EU member states, frontiers became the open “internal EU borders,” as, for example, between Poland and the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary, Hungary and Austria. Where they touched countries that so far have not received the invitation to join the European Union, the boundaries became “external EU borders” and thus subject to a whole new order of regulation and policing (for example, Poland-Ukraine, Poland-Belarus, Slovakia-Ukraine, Estonia-Russia). Between 2003 and 2008 I returned to Poland and Ukraine regularly to study the human consequences and political implications of this peculiar shift.

It affected the daily routines of state practice—border control and policing, traffic, and immigration bureaucracy—as well as the larger issues of geopolitics and foreign policy. The changes insinuated themselves also into the lives of many people—Poles, Ukrainians, and other non-EU citizens, in the borderland and beyond. Among such people were Anna Sadchuk and her family and friends.2 Anna was an itinerant Ukrainian worker in Warsaw. She was twenty-nine years old when I first met her in 2005, through a chain of encounters with other itinerant workers. Anna went to a vocational school to become a hair stylist, but in Poland she worked as a cleaning lady. She was a petite brunette with freckles and spoke in a soft voice that made her initially seem shy. That impression, however, dissipated halfway through our first conversation, at a café in her neighborhood one spring afternoon. She was a cheerful person with a penchant for telling stories, many of them having to do with the hazards and tricks of negotiating the border between Ukraine and Poland, the EU-imposed visa requirements, and the day-to-day perils of being an illegal migrant worker. “People here need us,” she told me,

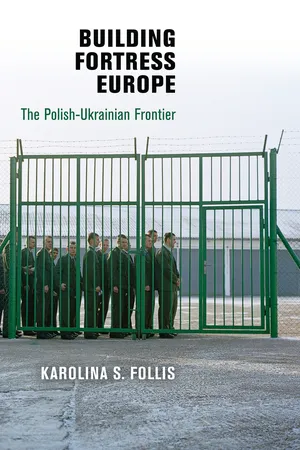

Figure 1. Map of the enlarged European Union. © European Union, 2011.

everyone in Warsaw has their Ukrainka, to do the work they don’t want to do. Polish women work in nice offices, wear nice clothes, they don’t have time to clean and cook. And so what are these visas for? Everybody knows that we’re going to come anyway. If we have to pay [bribes] we pay. If we have to lie [to the officials], we lie. . . . They [border guards] are not so stupid to think that we are coming on vacation. They know why we are here. They must check the visa, we must show the visa. And what? It changes nothing.

Anna, her brother, his wife, and her sister all come from a small town in the Lviv oblast’ (district) in western Ukraine. Together with two more female friends, they share a couple of boarding rooms in the attic of a neglected building in a centrally located neighborhood in Warsaw. Every morning they commute to their multiple, ever-changing, and unauthorized jobs all over the city. Anna was the youngest; her brother Dima was the oldest at forty. She has lived and worked in Poland intermittently since 1998, when she came for the first time with her brother to look for a job. Dima, like most male Ukrainian workers, has held mostly short-term jobs in construction. She started out picking and canning fruit and with time moved to better-paid urban house-cleaning jobs, where she was able to earn up to six hundred U.S. dollars per month (in 2006).3

Anna and her roommates, like thousands of other Ukrainians from their region and beyond, could not make ends meet back home. This has been due to persistent high unemployment that has marred the region since the collapse of Soviet-era industry and collective agriculture (official figures in 2008 were 8.3 percent for Lviv oblast’, but it is thought to be higher).4 The partial attempts at economic reform undertaken since 2005 have failed to address an overall scarcity of economic opportunity, felt acutely particularly in the rural areas of western Ukraine. Therefore, thousands of Ukrainians, primarily from the west, have been relying on the Polish szara strefa (gray zone, i.e., shadow economy) for employment. They come, because, as Elżbieta Matynia wrote in 2003, “even within ‘the East’ there is some place more west . . . enjoying relative economic success, proximity to the European Union, higher density of international transit on major highways, or greater strength of the local currency in relationship to the Euro” (Matynia 2003: 501).

The precise number of such migrants is subject to some dispute, but informed estimates range from 300,000 to 500,000.5 Poland’s young capitalism generates demand for cheap labor, especially in agriculture, construction, and private households.6 Because of its proximity, coming to Poland does not require the personal investment, risk, and expense that migrating farther west would entail.7 Yet Anna and others still negotiate a border regime which has thickened on EU’s eastward expansion, and which is built on the assumption that every non-EU traveler is a potential undesirable migrant.

But Ukrainian workers continue to cross the border.8 They adjust to the increasing constraints imposed by border regulations, but they also subvert and resist them. They exploit the economic opportunities enhanced by EU’s closeness, simultaneously connecting the Polish and Ukrainian societies through a web of relationships that are asymmetrical, but vital to both sides. At the same time they develop new ways of living away from their families, yet in permanent connection to a home where they cannot be physically present. “Every time I come here, I hope it’s the last time,” Anna told me one Saturday night when I visited her and her three roommates, Halyna (her sister-in-law), Nadia, and Ola. Permanently settling in Poland is neither their desire nor a real possibility. Ultimately, the objective is to go back to Ukraine, for Anna, her friends, and the vast majority of other itinerant workers. As we drank inexpensive Moldovan wine and ate Ukrainian cookies, the women told stories of their repeated border crossings and the scary, unpleasant, and funny things that happened in the course of their journeys. They recalled hustlers who hang out at border crossings and bus terminals and sign up women for “prestigious” jobs at nightclubs and escort services; all four women dismissed the possibility of ever doing such work, but they claimed to have had acquaintances who did. They talked about the bribes they needed to pay to customs agents when their hard-earned cash was found on them during return trips home. They explained how one can circumvent the border regulations and overstay the visa without running into trouble by altering the passport stamp, having the passport illegally stamped without leaving the country, or purchasing forged documents.

Some time after my encounter with Anna, and after having already completed several months of fieldwork and many trips across Poland’s eastern border, I attended a meeting of Polish and Ukrainian border professionals (which I discuss in detail Chapter 5). At that meeting, one of the Polish speakers, an NGO expert, started his presentation on combating illegal immigration across the new external border of the European Union with the following statement: “Let me tell you a secret: Poland does not have an immigration policy.” I wondered at the time why should that be a secret—after spending time among Ukrainian migrants, and learning about their lives beyond the official gaze, I was well aware that there was no policy to speak of that would lend any predictability or order to their arrivals and their work. Was the expert’s declaration just rhetoric to spark interest, or did it signal recognition of a serious problem? The remainder of the presentation covered in great detail the current ways of policing Poland’s eastern border and preventing illegal migration, but the speaker did not revisit the issue of the lack of an immigration policy. As this study progressed, however, I began to understand that the answer was implicit in his presentation, and was confirmed by the activities of multiple agencies, such as the Border Guard and the Aliens Bureau, involved in border issues. Poland indeed did not have an immigration policy, or, for that matter, one pertaining to the broader realities of postsocialist mobility; the “secret” was that the new border regime, developed in the context of joining EU and the Schengen territory without internal frontiers, was a surrogate for one. This elision of vital matters of human mobility, legality, and territoriality within the new border regime has become the central theme of this ethnography.

This book is about the rebordering of Europe on the Polish-Ukrainian frontier between 2003 and 2008. I connect experiences such as Anna’s to the complexities and intrigues of the new border regime, as I have reconstructed them from my encounters with border guards, officials, and experts involved in its formation. This research supports my contribution to the larger scholarly conversation addressing the question of what borders are today, in a time when European states are engaged in a project of supranational integration and traditional sovereignty is being redefined; when capital, goods, and people move transnationally in staggering numbers and at an unparalleled speed; and when populations and individuals are subjected to the workings of the variable modes of post-9/11 securitization. The dismantling of the Iron Curtain in 1989 had a massive impact on the social and political geography of the continent, human mobility, and ways of thinking about territory and populations. With the post-2004 reconfiguration of borders in Europe, these adjustments and rearrangements call for reassessment.

Borders as Objects of Social Inquiry

This project began with the observation that in the post-Cold War world, few other political artifacts have been at the core of quite as many pressures and hopes as that of an international border. The state’s exclusive control over its territorial boundaries has been one of the key markers of state sovereignty (Anderson 1996; Andreas and Snyder 2000; Balibar 2002, 2004; Benhabib 2004; Chalfin 2003; Donnan and Wilson 1999; Dudziak and Volpp 2006; Giddens 1985; Hobsbawm 1990; Krasner 1999; Sassen 1996, 1999; Torpey 2000; Walters 2002, 2006). However, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, a complex of social, economic, and political transformations complicated the terms in which modern sovereignty has been understood. Has globalization, thought of loosely as the rise of transnational flows, combined with increasing flexibility of capital and growing power of corporations and other non-state entities, undermined sovereignty? Or rather, has it forced the state to reassert its power in new ways by different means? (Appadurai 1996, 2001; Chalfin 2003, 2004; Anderson 1992; Kearney 1995; Sanders and West 2003; Sassen 1996; Trouillot 2000). Notwithstanding the importance of this debate, I bracket, for the time being, the question of sovereignty’s contemporary modalities, the status of the nation-state, and its possible future. Instead, I want to focus on the fact that in this context international borders are fundamentally changing their character. They are being reinvented as sites of mobility and enclosure (Cunningham and Heyman 2004), broadening the scope of transnational possibilities but also indicating their limits.

Scholars across disciplines have asked whether international borders are opening up or closing. Are they becoming more or less permeable, more or less important, for whom, when, and why? This wide-ranging research has yielded a set of partial certainties. Globalization, technological progress, and contemporary “fast-capitalism” (Holmes 2000) do spur transnational flows and a circulation of people, objects, and ideas to which international borders are no obstacle (Appadurai 1996; Castells 1996). The ability to experience the world as borderless is, however, a privilege whose distribution hinges on the variables of class or economic status, nationality and citizenship, gender, ethnicity, race, religion, politics, and geopolitics. (Anderson 2000; Ehrenreich and Hochschild 2004; Balibar 2002; Blank 2004; Bornstein 2002; Cunningham 2004) First World democracies have been erecting walls around themselves since long before the planes hit the Twin Towers (Andreas 2000b; Andreas and Snyder 2000). Afterward, a new “governmentality of unease” (Bigo 2002) has crept into international border controls and fears of terrorism, meshed with older anxieties about excessive immigration and the ostensibly rampant “abuse of asylum” (Lavenex 1999; Bohmer and Schuman 2007). We have thus seen a progressive securitization of borders (Rumford 2006; De Genova and Peutz 2010). This in turn entails a rapid advancing of biometric technologies to control human mobility as well as an erosion of freedom of movement, and of human rights guarantees to vulnerable groups and individuals in transit. In this context, some scholars have presented compelling Foucaultian and Agambenian analyses of the specific biopolitics involved in deploying borders as enclosures, and of the zones and states of exception emerging at the limits of the normal legal order (Foucault 1990; Agamben 1998; De Genova 2010; Fassin 2005; Giorgi and Pinkus 2006; Landau 2006; Minca 2006). Refugee camps, detention centers for illegal migrants, and other holding spaces for the unwanted and the deportable have been placed on a historical continuum with other states of exception, where the “suspension of the usual social norms is accepted . . . because it is implemented for ‘undesirable’ subjects” (Fassin 2005: 379). The historically and contextually specific constructions of “undesirability” have also been studied and critiqued, often with respect to their legal production (Coutin 2003, 2005; De Genova 2002; Kelly 2006; Silverstein 2005).

These works differ in critical emphasis, but by and large they highlight antidemocratic, ethically dubious, and socially unjust elements of state and policing practice, often relating them to the historical trend of contemporary states to withdraw from responsibility for human welfare, broadly associated with the ideology of neoliberalism. My project is indebted to this scholarship, but it attempts to chart its own path. I draw on empirical data collected in Poland and Ukraine to ask how borders, as both gateways and enclosures or exceptions, fit into the larger process of the expansion and evolution of the European Union as a novel type of a supranational, ostensibly democratic political community. Which forms of agency, belonging, and habitation do they enable or disallow? Which social and spatial imaginaries do they support and which support them?

I pose these questions because borders and border zones are not merely margins of polities, but play a central role in their constitution. Given that the European Union appears to be an entity in a perpetual state of emergence, I shall focus on how it is actualizing itself through the complex efforts of establishing its own eastern external border. I will look at the frictions these efforts produced in a particular place, at the particular moment of expansion. Some of these frictions—for example, between national and EU authorities; local community and national government; economic and security interests; human rights commitments and exclusionary tendencies—are emblematic of the larger tensions and contradictions in the construction and consolidation of the enlarged European Union.

Addressing these questions requires a dynamic concept of the border, one that would account for both its inherent connection to territory, as a frontier or a borderland, and the fact that today this connection is being (partially) severed. Beyond the material, such a concept must capture also the symbolic and discursive life of borders, that is, their relationship to boundaries understood, in the classic Barthian vein, as the separation of self from other which lends meaning to identity (Barth 1969, 2000; Cohen 1986, 2000; Stolcke 1995).

In 1995 Robert Alvarez noted à propos the literature on the U.S.-Mexico border that “some scholars feel that to take a metaphorical approach to borderlands distracts us from social and economic problems on the borders between the nation-states and shifts the attention away from the communities and people who are the subject of our inquiry” (Alvarez 1995: 449). He pointed out that “literalists” focused on what they saw as “the actual” problems of the border, such as migration, policy, environment, identity, labor, and health. ‘A-literalists’ in turn account for social boundaries on the geopolitical border and for the contradictions, conflict, and shifting of identity characteristic of borderlands (Alvarez 1995: 449, see also Cunningham and Heyman 2004). In recent years the dichotomy of literalist and a-literalist approaches has blurred (Donnan and Wilson 1999; Berdahl 1999; Inda 2006; Pelkmans 2006), and new conceptualizations of borders are at their richest when they draw on both of these distinct genealogies.

Hastings Donnan and Thomas Wilson suggested a definition that names and systematizes the domains wherein borders operate:

Borders are signs of the eminent domain of the state, and are markers of the secure relations it has with its neighbors, or are reminders of hostility that exists between states. Borders are the political membranes through which people, goods, wealth and information must pass in order to be deemed acceptable or unacceptable by the state. Thus [they] are the agents of a state’s security and sovereignty. . . . Borders have three elements: the legal borderline which simultaneously separates and joins states; the physical structures of the state which exist to demarcate and protect the borderline, composed of people and institutions which often penetrate deeply into the territory of the state; and frontiers, territorial zones of varying width, within which people negotiate a variety of behaviors and mean...