![]()

Chapter 1

Earthwork as Framework

or How Topography Exceeds Itself

Do the geometries and dimensions of landform prescribe those of building-form? Are constructions that lie below the surface of the land and those that stand upon it one—not two—kinds of work? Does (should?) substructure prestructure superstructure? If this seems acceptable in landscape architecture, if it can be granted that types of terrain give rise to plantings of various kinds, it is surely less obvious that other surface articulations, buildings, are similarly preformed by the levels, geometry, and materials of their location. The single question to be addressed in this investigation is whether or not the design and construction of buildings, the sorts of “frameworks” usually called architecture, can be understood as “outgrowths” of site preparation.

A number of important recent projects suggest that architecture can, indeed, be understood as a “flowering” of cultivated and constructed sites—of landscape. One of these, the Neurosciences Institute in La Jolla, California, designed by Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, exemplifies this stance clearly. The building rewards study for many reasons, but as a “garden in stone” it is particularly apposite to the question concerning the relationship between landform and building form. Before considering that building in detail, however, it will be useful to recall briefly three historical antecedents for the approach it represents, to distinguish the real challenge of its intentions. Each of the three—a path, house, and “primitive hut” from the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries—illustrates the dependence of a spatial enclosure on its underlying and substrative part.

A GARDEN PATH

Landscape theorists in the past have suggested that buildings do, indeed, depend upon and elaborate the characteristics of the terrain in which they are located. C. C. L. Hirschfeld, whose Theory of Garden Art (1779–85) provides an impressively thorough account of the modern—which is to say postbaroque—tradition in garden design, treated garden buildings (pavilions, summerhouses, ruins, temples, etc.) as extensions, developments, or elaborations of garden terrain, especially of paths.1 Just as decks can be formed by widening walks, so porches or verandas can be made by covering them. If garden paths accommodate movement by conforming to and accentuating the contours of underlying terrain, well-sited buildings do much the same. The most common of earthworks, retaining walls, support and sustain open-air and enclosed circulation routes, whether lined by hedges and trees or roomed in. Hilltop plateaus and prospects from them also suggest the dependence of super- on substrata. Landform is the outlook’s first premise because without a raised level neither that sort of view nor its framework would be possible. When both paths and pavilions are seen as ornaments of the land, as they are in the concluding statement of Hirschfeld’s first paragraph on buildings, their similarity is assured: “Both architecture and sculpture also strive to contribute to garden decoration.” Here decoration does not mean something accessory or adjunctive, but something that improves, accentuates, or crystallizes the terrain’s characteristics.

If this seems overdetermining or constraining for architecture, there is an alternative understanding of the relationship between earthwork and framework. Modern architecture presents a great number of buildings that seem to have been placed “on the land,” as if they were designed without regard to the particulars of their place. Indeed, a number of famous buildings were designed for one location and then built on another, without changes to the design. James Stirling’s History Faculty at Cambridge University is a case in point. Already in the middle years of the twentieth century Frank Lloyd Wright implied that the deployment of place-free plan patterns had become a common practice, even if, on his account, it was wrongheaded. His arguments for building “with” not “upon” the land in The Living City proposed the opposite: a coupling of landform and building-form.2

A TERRACED HOUSE

Many not so famous examples also suggest the portability of design concepts. Cities and suburbs are full of constructions that have unaltered counterparts elsewhere. Repetition is not the exception, but the norm in traditional domestic architecture. An obvious example is terraced housing, as it developed in London and other British cities and was exported to other countries. Despite its ubiquity, the name of the type implies that a particular site condition was essential to the building’s form. Before the building’s upper framework was constructed, half basements were cut into the ground. The excavated soil was not carted away but mounded up to form a level street in front of the row of houses. This level was the terrace. Its edges were formed by retaining walls that resisted lateral pressure on one side, enclosed an undercroft on the other, and supported the sidewalk above. To see the height that a typical London terrace was raised above the original ground level one must only descend to the “area” between the sidewalk and house, or stand at the level of the “mews” behind the house and see the slope of the ramped street that rises to the level of the side or front street. Once this lower part was established, the building’s upper parts were constructed. Although the sub- and superstructure were compatible, the framework did not “elaborate” the earthwork. Excavation and terrace building cleared a level into which walls were cut. The building was not an outgrowth of the land but an insertion into it. Its upper parts were not worked out of lower ones but dug into them. Thus it is a different kind of base than that of a garden pavilion: not a substructure but a substratum, not an underground vertical but a ground-level horizontal, into the cleared surface of which the building’s walls were set.

A PRIMITIVE HUT

Recently the joint necessity of the building’s lower and upper parts has been argued by Kenneth Frampton in his condensation of Gottfried Semper’s four elements of architecture into this pair: earthwork, the building’s topographical footing, is seen to comprise both the base platform and the hearth (or any of its similarly social modern equivalents), while framework, the building’s orthogonal system of enclosure and compartition, is thought to include both vertical structure (including roofing) and walling.3 Semper’s division of the four elements was not, however, into two pair; instead, he grouped three of the four together—the mound, roof, and enclosure—and all of them separate from the hearth because they surround it. They also follow it, chronologically and ontologically. To understand this one must distinguish a building’s system of support from its (social) starting point, although both can be described as its basis. The origin of the art of building coincides with the beginnings of society, the gathering of people for religious or social practices. The communal situation (around a fire) was so significant to ancient peoples, Semper argued, that earthwork and framework were always subordinate to this initial and fundamental situation (and its constructed correlate). Their cooperation in providing support for the social events suggested a mutuality of land and building-form. Their relationship is one of collaboration in service of the communal events at their center. The results of mounding and framing reciprocated one another as props of practical affairs.

The relationship between a building and its site can be understood, then, in any one of three ways: the building as an elaboration of the terrain, an insertion into it, or something that works (toward social ends) in collaboration with it. Many other examples could be introduced to exemplify these approaches, but the three just described should be sufficient to provide a context for more recent interpretations of the earthwork-framework relationship.

TOPOGRAPHY EXCEEDING ITSELF

A number of important recent projects suggest a different and more challenging proposition for the interconnection between building and site, that the building is not substantial on its own terms, nor self-sufficient, but contingent, dependent, or adjective to its milieu. While still managing its own affairs, site construction (landscape architecture’s most basic pretext) is now used also to determine the building’s overall massing and discrete settings, as if it were structure, not only binding the two together, but making the second—the building—an attribute of the first. The idea of adjectival architecture extends a commonplace of contemporary criticism, that the site should “structure” the project.

Under this new dispensation, site—or, more broadly, ambient landscape—is not what surrounds and supplements the building, but what enters into, continues through, emanates from, and enlivens it—rather like fire taking hold of a piece of wood. In other words, landscape, or simply land (environment, climate, region), has reclaimed all that was once taken from it: materials, spatial extent, lighting effects, “atmosphere,” and so on. Topics that have always been essential to landscape description (natural processes, materials, etc.) now also dominate discourse about buildings. This explains why certain themes and techniques have come to be emphasized so strongly in contemporary criticism and practice: sustainability, temporality, and “registration” in the first case, surveying, mapping, and phasing in the second. All of them are basic to working with land.

The reasons for this spread and sharing of terms and techniques are no doubt complex, but beneath the surface of the many arguments for architecture’s reengagement with its milieu are signs of guilty conscience concerning past buildings that neglected (and often disturbed) the places in which they were located. More specifically, the redefinition of architecture as (part of) landscape attempts to answer a number of questions that have been nagging theory and practice for too long: how can the design of a building acknowledge the particularity of place when construction practices utilize elements and technologies that obey no territorial obligations? Can building materials that are found in the project’s vicinity still play a role in determining architectural form when newer alternatives are known to be less expensive and more serviceable? How can the technical and aesthetic operations of a building acknowledge the natural or ecological processes that characterize its location? And, finally, how can the very personal aesthetic preferences of designers be mediated by conditions that are necessary to the project?

The Neurosciences Institute by Williams and Tsien demonstrates more clearly than many designs the promise of seeing the relationship between building and landscape as a matter of dependency or descendancy—the first on or from the second. A simple question about the making of discrete settings within the landscape can be used to begin the interpretation: what is basic to the definition of a place within an extended and articulated terrain?

2. Neurosciences Institute, La Jolla, California, Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, 1992–95, façade from North Torrey Pines Road (photograph: Anna Catherine Vortmann).

The creation of a shadow, suggests Sverre Fehn, is the origin of architecture, or, more modestly, of a place. Darkness so created must exist for clarity to be apparent by contrast, whether it is the clarity of a setting, a thought, or scientific research. Land, no doubt, offers a surface on which this shadow can appear; can its forms also construct the shadow’s projection? When asked by Peter Zumthor to identify a beautiful place, Billie Tsien recalled a setting within the Neurosciences Institute, “the circular, outdoor space where you can sit and look at the fountain, which gives you a long view.” It was one, she said, that made her completely happy.4 Earlier in the interview she responded to a question about “interior landscapes” by describing a certain kind of “excavation”: a room, she observed, “is more than a mark in the land. There’s the rootedness which happens from cutting away, making a hole in the land, and then there is the extension that has to do with the sky and that sense of infinite escape.”5 The pairing of these two spatial motifs, excavation and extension, exists in many analogous forms in this project. Each was built out of the folds of the terrain as a site of contrast and complementarity between darkness (of the land) and clarity (of the prospect). A first answer to the question about place making is that settings are defined when land is “cut away.” More technically, the builder’s act, like the designer’s view, is essentially a slice: the primary tools of the architectural trade are analogues of the knife—the pencil and the spade.

TOPOGRAPHY OPENING ONTO ITSELF

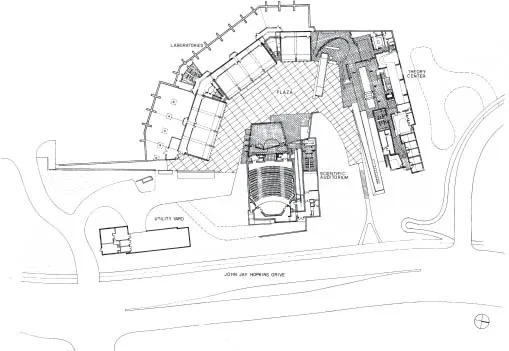

The “circular outdoor space” to which Tsien referred serves as an eccentric meeting point of a number of pathways through the project: one from the southward bays of the laboratories for experimental research toward the dining room, another toward the offices for administration and theoretical research, still another (but above and through a tunnel) to the rest of the campus westward, and a fourth toward the distant landscape beyond the gap between the ramp to the theory building and the façade of the auditorium to the east. The confluence accomplished by this nexus of routes integrates more than paths through the building, however; concentrated there also are salient characteristics of the extended landscape.

3. Neurosciences Institute, La Jolla, California, Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, 1992–95, view from circular court (photograph: Anna Catherine Vortmann).

4. Neurosciences Institute, La Jolla, California, Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, 1992–95, plan.

Beyond the building’s immediate vicinity, down the slope and into the distance, the land’s surface shows only slight modulation. Although now a patchwork of trees clutters much of the terrain, when the building was just finished the “long view” Tsien intended was uninterrupted. Then the prospect’s depth of field did not result from layering, from foreground figures occluding aspects of those that stand in the middle and background (as it does now), because all of the figures were rather indistinct in profile and undistinguishable in species: mostly a tangle of underbrush spread across terrain that was otherwise barren. Much of this remains, despite the recent arrival of some buildings nearby and a tree screen that has risen to filter the prospect. Such slight inflectio...