![]()

Chapter 1

Almshouse Bodies

During the 1780s and 1790s Joseph Marsh, Jr., compiled a series of hefty ledgers. Today Marsh’s dusty and crumbling Daily Occurrence Dockets of the Philadelphia Almshouse lie in the Philadelphia City Archives, and they constitute a detailed inventory of the bodies of distressed and suffering Philadelphians who—whether by choice or not—found themselves passing through this “asylum of beneficience.”1 The almshouse was a vital part of Philadelphia’s limited system of poor relief, a place containing “all that misery and disease can assemble,” wherein the bodies of the poor were incarcerated, cared for, and reformed.2

On occasion, Marsh’s language suggests that he was moved by the condition of those who entered the almshouse. John Smith was admitted “lame naked helpless & Distressed for every Necessary,”3 and Isabella Wallington came in “almost naked & every way wretched & abandoned.”4 Ambrose Robinson was “a decent looking old Man” whose work with arsenic in dyeing fabrics had occasioned a stroke and rendered him “much Debilitated,” while an old black man named Thomas White was so “much emaciated with disease and swarming with Vermin” that staff were forced to strip and clean him and burn “all the Cloaths he had on—which were indeed only Rags & not worth any trouble to clean them if it were even practicable.”5

For every one of Marsh’s humanitarian sentiments, however, there were many more expressions of strikingly caustic and negative judgments, symptomatic of a larger social tendency to regard all the poor, regardless of the cause of their poverty, as morally and physically responsible for their situation and condition. For every kind word Marsh penned many more cruel ones, and some of the poorest and most distressed of Philadelphians were dismissed as “a very worthless old Woman,” “a sullen Idle fellow,” or even “lame and worthless.”6 Marsh accurately reflected the values of middling and elite Americans who believed that they could differentiate between the deserving and undeserving poor: the former were those who through no fault of their own were unable to keep themselves and their dependants, while the latter were fit, healthy, and able to work, but sought to take advantage of poor relief. In the fast expanding city, Marsh and his ilk were inclined to treat an ever-increasing proportion of the poor who passed into the almshouse as undeserving. The almshouse records—indeed, the institution itself—illustrate how close many lower sort Americans were to dire poverty and dependence of a sort that the elite could hardly imagine, but which they were quick to judge.7

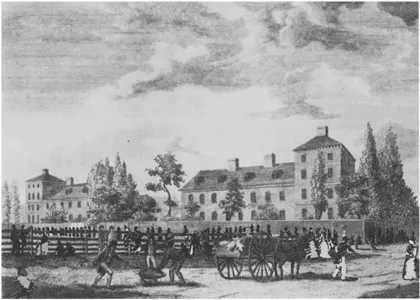

The Daily Occurrence Dockets show the bodies of the poor being evaluated and held accountable by the Overseers of the Poor and the city they represented.8 Better food and kinder treatment were regularly withheld from those judged undeserving. The almshouse authorities required them to work, in part to help defray the expense of their upkeep and in part to prepare them for work outside the almshouse, so that these troublesome indigents might be released back into the city as better and more productive citizens. But although the differentiation between deserving and undeserving poor persisted, almshouse residents were increasingly judged, incarcerated, and conditioned as a single group of dangerously poor and undesirable bodies.9 As the city and population of Philadelphia mushroomed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, with an accompanying rise in urban poverty, the almshouse played a crucial role in controlling and remolding the bodies of the ever-increasing mass of impoverished urban residents. Such treatment and control were, however, contested by many residents, and early national Philadelphia’s almshouse was the site of many struggles for self-determination by thousands of poor, ill, homeless, and socially undesirable bodies. To the elite and middling Philadelphians who constructed, organized, and ran the almshouse, the bodies of the poor were improvement projects, to be undertaken and accomplished. To impoverished Philadelphians in the almshouse, however, their bodies were often virtually all that they owned and thus the primary means whereby they might achieve some measure of control over their own lives. Just as seafarers like Augustus Reading celebrated their membership in a working group of low social status with distinctive dress, tattoos, and language, or black slaves and servants like Dick sought some measure of personal integrity through distinctive dress, hair styles, and bodily adornment, many of those in the city’s very lowest ranks used their bodies to carve out some small degree of independence.10 Embattled bodies populated the almshouse, defining a contest between the authorities who saw residents’ bodies as objects to be controlled and residents who defended their bodies as the loci of individual agency and power (Figure 7).11

The status and indeed the very nature of the impoverished lower sorts who passed through the almshouse were recorded in explicitly moral terms based upon observation of their bodies. Bodily appearance and actions were both crucial here, and such factors as demeanor, stature, clothing, and intemperance all contributed to the ways residents were judged. The Daily Occurrence Dockets are filled with bluntly formulaic assessments, “embodied characterisations”12 of the deserving poor, like Hugh Stewart, “an orderly useful old man,” or the undeserving, like Mary Chubb, “a very worthless body often here.”13

Figure 7. William Birch, Alms House in Spruce Street, Philadelphia, 1799. Based on the original at the Library Company of Philadelphia, with additions by Anthony King. While the almshouse lay on the outer reaches of the settled area of 1790s Philadelphia, it was only four blocks west of the Walnut Street Jail and was hardly the pastoral paradise presented by Birch. Farmers passed by as they brought their produce to market, but this was a building of the urban and transient lower sort, men, women, and children who were incarcerated and made to work within its walls. The fence made escape from the none-too-tender care of the almshouse keepers difficult but far from impossible, and especially during the warmer months many decamped from the “bettering house,” only to be incarcerated again, whether by choice or not, during the colder winter months. As the largest residential structure in the city, it was a place defined by the people who lived within, and by those who sought to control and “better” them.

To Marsh and those who administered the almshouse, it was all too clear that they were dealing with bodies as objects to be controlled and shaped, rather than as subjective entities to be respected, with the result that the Dockets often dismissively refer to people as no more than bodies. In some cases the tone was one of approval, as in the case of Clara McCord, “an orderly quiet old Body [who] Spins industriously,” or Elizabeth White, “a very orderly willing Industrious old Body Knits &c.”14 More often, however, bodies were described and dismissed in more negative terms. The only words used to describe Ann Newgent were “a very so, so, body,” while Elizabeth McClinch, “this vile little drab,” was dismissed as “a very worthless Idle body.”15 Bodies were objects, even property, as in the case of Sarah Summers, “Lately imported from England,” or the former servant Sarah Overturf, “who was unsound (blind) when imported.”16 However, while the poor condition of male bodies was often noted in the records, it was only women who were dismissively referred to as “bodies” by Marsh; given that women of this era were far more likely than men to be referred to as “nosybodies,” “busybodies,” and the like, it may be that it seemed appropriate and even natural to reduce impoverished women to the status of unworthy and unsound bodies in the almshouse records.

The rapidly growing number of impoverished bodies populating Philadelphia appeared problematic and even dangerous, threatening to run out of control, break down social order, attract and spread disease, and generally contaminate the carefully ordered urban society of the new republic.17 Admitted time and time again was Robert Aitken, “the worthless, drunken Laughing Barber,” “as Lousey filthy & dirty as ever.” The prostitute Sarah Simpson was recorded as “a woman & one of the Softer, or tender Sex—for she is very soft and tender, as to be nearly or quite Rotten with the Venereal Disease,” while Ann Johnson was brought from her usual spot near the Coffee House, “a drunken derainged old Woman, brot on a dray very drunk almost naked & near Pewking.”18 People such as these were undesirable, ill fitting the model republic desired by the men and women of means and property and imagined by Birch. To keep society and indeed the republic safe, these troublesome bodies had to be incarcerated and then refashioned: once cleansed, reclothed, and trained to work, these bodies could return to the community as members of the respectable and deserving poor, who would employ their bodies in subservient work and present themselves in an appropriately deferential fashion.

The Daily Occurrence Dockets, then, tell us something of the ways social control was exercised over distressed and impoverished bodies. But these were lived bodies as much as they were objective bodies, and how these men, women, and children experienced hunger, nakedness, cold, filth, disease, and drunkenness, and the ways they chose to employ and resist the almshouse and its system of poor relief, can tell us much about life and culture among the very lowest of the lower sort.19

For centuries, European and then colonial American civil authorities had attempted to differentiate between the deserving poor, whose distressed situation was no fault of their own and who merited charitable assistance, and the undeserving poor, who were responsible for their condition and required discipline and subordination. According to the sixteenth-century English commentator William Harrison, for example, the former group of poor “by impotency” or “by casualty” included “the fatherlesse child,” “the aged, blind, and lame,” “the diseased person that is judged to be incurable,” “the wounded soldier,” “the decaied housee-holder,” and “the sicke persone visited with grievous … diseases.” In contrast, the “thriftless” poor included “the riotour that hath consumed all,” “the vagabound that will abide no where,” and “the rog[u]e and strumpet.”20 These categories were more than familiar to early national Philadelphia authorities, and they were employed by Joseph Marsh as he made entries in the Daily Occurrence Dockets.

Philadelphia’s almshouse was intended to function as both a refuge and a prison.21 For the deserving poor the almshouse provided shelter and even a rudimentary hospital, a place of last resort where the ill and wounded might recover or die peaceably, where those without support might live and work, and from which some might be bound out to serve others. Alternatively, city officials or night watchmen often interned the bodies of the undeserving poor for whom the almshouse was a place of correction, even a prison, and a growing proportion of those entering had been arrested in this manner. Located on Spruce Street, the almshouse’s imposing buildings lay on the outskirts of the densely populated urban core. Apart from the streets and public places, the almshouse and its workhouse were intended to force such people who appeared fit and able into socially acceptable and productive lifestyles. This dichotomy between sanctuary and prison was reflected in the policies of the Guardians of the Poor, the city officials with responsibility for poor relief and the almshouse, who sought to “take great care to make proper distinctions between the different Classes in separating with Regard to their several Characters & Conduct.” Such differentiation was all too real for the men and women who passed through this system: while the deserving poor might enjoy tea, for example, undeserving prostitutes suffering from venereal disease faced a diet of bread and water.22

J. P. Brissot de Warville fully appreciated the dual purpose of the almshouse, entitling his description “Visit to a Bettering-House, or House of Correction.” He described the almshouse as being “constructed of bricks, and composed of two large buildings; one for men, and the other for women.” Included among its residents were “the poor, the sick, orphans, women in travail, and persons attacked with venereal diseases … vagabonds, disorderly persons, and girls of scandalous lives.” The two wings were subdivided into various rooms and wards “appropriated to each class of poor, and to each species of sickness.” While impressed by the almshouse, an experienced European like de Warville was nonetheless horrified by the interior scenes of “misery and disease.”23

The brief yet illuminating descriptions contained in the Daily Occurrence Dockets illustrate that there were residents who met the Overseers’ criteria for deserving poor, people whose bodies were too sick, diseased, injured, or aged to enable their owners to support themselves. James Berry, for example, had continued to work hard despite a sore leg, possibly the result of a painful case of gout. He was admitted in the spring of 1791 as “a poor man, who hath long labour’d under the affliction of a very bad sore leg; & which same leg was again unfortunately caught & severely mash’d between two Hogsheads or Casks last Monday.” Full of sympathy for an honest working man who could no longer work, the clerk maintained that Berry “is therefore of real Necessity sent in here.”24 Daniel McCalley and his five-year-old son were admitted because he was “an old man & lately much hurt, at his work, at a mast yard.”25 Similarly, Murdock Morris was admitted as “an old Higlander formerly a laborious man now rhumatic,” just as James Smith, “a Ship Carpenter, looks as if he hath been a laborious working-man—now ill with rheumatism &c.,” while the old soldier William Payne was “mostly full of ulcers and sores, yet he works duly...