![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Ethos of Moderation

What then is the spirit of liberty? I cannot define it. . . . The spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure that it is right; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which seeks to understand the minds of those men and women; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which weighs their interest alongside its own without bias.

—Judge Learned Hand

When Things Fall Apart . . .

Yeats’s hauntingly beautiful verses from The Second Coming offer one of the best introductions to a book on political moderation in the twentieth century.1 Here is the Irish poet lamenting the unraveling of the center and the coming of anarchy:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity. (1962: 99–100)

“Surely, some revelation is at hand,” the poet added. And what a revelation it was!

The “rough beast” whose hour came “round at last” and which slouched “toward Bethlehem to be born” was the herald of a bloody century whose balance sheet speaks for itself. Things did fall apart (and not only once) and the center failed to hold precisely when it was most needed. The “worst” proved to be extremely active and full of “passionate intensity.” They started, among other things, two devastating world wars, embraced ruthless ideologies that justified the murder of almost a hundred million innocent people in the name of deceiving or criminal ideals, used extensive propaganda techniques and brainwashing methods, and were instrumental in creating mass-scale terror, forced labor, and extermination camps. As the distinguished Spanish essayist and diplomat Salvador de Madariaga once put it (1954: 5), “reason and liberty are precisely the two martyrs of our age.” Many words such as equality and liberty had to change their ordinary meanings and were given new ones that sought to distort the reality on the ground. Reckless overconfidence came to be regarded as manly courage, while prudent hesitation and careful consideration of facts were deemed to be forms of treason or cowardice. Moderation was held to be a cloak for pusillanimity, and the ability to see and take into account all sides of a problem was denounced as incapacity to act on any. Fervent advocates of extreme measures were often deemed to be trustworthy partners, while their opponents were regarded with suspicion and dismay.2 Albert Camus was right then to begin his account of revolutionary ideologies in The Rebel with a dark conclusion. In his view, “slave camps under the flag of freedom, massacres justified by philanthropy or the taste for the superhuman” (1956: 4) represented the dark side of the past century that nobody could excuse or ignore any longer.

The seeds of destruction, however, had been planted long before under our own eyes. In the wake of the Paris Commune whose bloodiest episodes brought back the memory of the revolutionary Terror, Rimbaud had proclaimed, “Voici le temps des assassins!” How prescient the poet was! If the nineteenth century was a century of hope, the one that followed, the most political century in history, turned out to be extremely violent and cruel. With the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914, Europe entered a long “age of anxiety” after a century of relative calm and prosperity. The drumbeat of barbarism sounded in the very heart of the civilized world before setting the entire world aflame. The Bolsheviks drew direct inspiration from the Terror of 1793–94 and invented a new style of politics that showed in plain daylight how fragile and unstable the hold of civilization is. For all the great and undeniable achievements of the past century—the rise of the average human life expectancy, the eradication of many illnesses, the conquest of the space, the outlawing of various forms of discrimination—the two totalitarianisms that originated in Europe (fascism and communism) constituted new forms of barbarism with a modern face that cast a long shadow over the entire world. Whether we like it or not, we are heirs to an epoch that produced Hitler, Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot, larger-than-life tyrants whose hubris far surpassed the lust for power of their predecessors. Confronted with these distressing facts and numbers, even Voltaire’s Candide would have paused for a moment to question the idea of progress and might have been inclined to abandon his proverbial sunny optimism.

Today, the decades from the 1920s to the 1960s may seem a part of another world reinforcing the belief that the past is a foreign country. But as we look at the world around us, we realize that this is a costly illusion. Simone Weil was probably right to argue that “modern life is given over to immoderation. Immoderation invades everything: actions and thought, public and private. . . . There is no more balance anywhere” (1997: 211). Our undeniable technological advances have not been matched by corresponding progress in the realm of morality. As Norberto Bobbio remarked (2002: 191), “we may be technologically literate but many of us are still morally illiterate. . . . Our moral sense develops, always supposing it does develop, much more slowly than economic power, political power, and technological power.” That is why, as we enter our own (postmodern) age of anxiety fraught with new dangers and challenges, it might be timely and necessary to examine how twentieth-century European intellectuals responded to their challenges and sought to preserve the values of civilization threatened by the rise of totalitarian ideologies and secular religions such as Nazism and communism.

I am a child of that century, having been born during a postwar period known in the West as les trentes glorieuses; alas, the Eastern part of the old continent where I grew up was not that lucky. After the Iron Curtain fell over Europe, the entire world became divided into two separate worlds that waged a long and costly Cold War. Life under communism had many shortcomings, to use a euphemism, but it taught me at least two important lessons. The first one was that, after all, there is no fundamental distinction between the “brilliant” future envisaged by the founders of Marxism and the real communism that was offered to us as a gateway to a perfect tomorrow. What I saw with my own eyes was not a perversion of the ideals of Marx or Lenin; it was actually, for the most part, the realization or consequences of their own principles. The real communism that existed in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union implied not only the triumph of the proletariat, but also the monopoly of a vanguard elite showered with obscene privileges denied to the majority of citizens, the persistence of severe economic shortages for the masses, the strict punishment of dissenters, the conscious promotion of incompetence over competence, unrelenting official propaganda, and the omnipresence of the secret police that relied on constant spying and denunciation. The second lesson that life under a totalitarian regime taught me was about the fragility of freedom and the importance of political moderation as an antidote to zealotry and fanaticism.

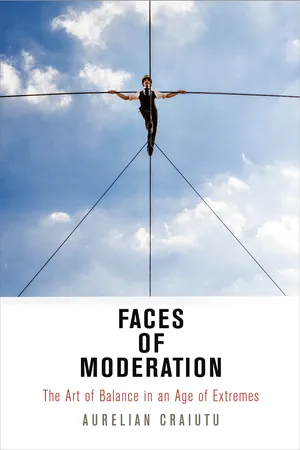

Moderation, the subject of this book, is therefore, at least for some of us, a legitimate reaction to the violent age of extremes in which we have lived. It is one of those key virtues without which, as John Adams once said (1954: 92), “every man in power becomes a ravenous beast of prey.” But I have also come to regard it as something much more than a circumstantial (contextual) virtue or a mere character trait. The argument offered in this book is that moderation, in its many faces, is a fighting and bold creed grounded in a complex and eclectic conception of the world. A great advantage of the latter is that can be shared by diverse actors on all sides of the political spectrum (not only in the center!) in their efforts to promote necessary social and political reforms, defend liberty, and keep the ship of the state on an even keel. Because it rejects ideological thinking, moderation implies a good dose of courage, non-conformism, flexibility, and discernment, as suggested by the image chosen as the cover of this book. Finally, as a tolerant and civil virtue related to temperance and opposed to violence, moderation respects the spontaneity of life and the pluralism of the world and can protect us against pride, one-sidedness, intolerance, and fanaticism in our moral and political commitments.

A Challenging Virtue

To be sure, this is not how moderation is usually perceived today when it seems particularly difficult to articulate a convincing and effective philosophy of this elusive virtue. At first sight, few ideas might seem more quixotic than moderation in modern politics. Why did so many intellectuals eschew it and fall under the sway of grand schemes of social and political improvement that led to mass poverty and terror? Following Plato’s example, they searched for their own “Syracuse”—be that Moscow, Berlin, Havana, Beijing, or Tehran—or visited “Syracuse” in their own restless imaginations. Many of them willingly offered their services to tyrants, defended the indefensible—that is, cruel regimes that displayed no regard for human dignity and liberty—and defiantly ignored the lessons of history, often choosing authenticity and adventure over humility, decency, and moderation.3 Others felt increasingly alienated in modern society and spoke as prophets of extremity, in search for radical cures to the ills of modernity. Some of them (Heidegger) took to task the legacy of the Enlightenment, while others (Foucault, Sartre, Derrida) spoke in the name of the ideas of the Enlightenment and used them in order to diagnose and criticize the malaise in our political and social institutions. Finally, a select few gave up politics altogether and retreated into their own mythical “Castalias” or withdrew into their hermitages of pure thought, often on the top of a “magic mountain,” far away from the sound and fury of the world, preparing themselves for the appearance of the last gods.

Whatever the reasons for their political and existential choices might have been, one thing is obvious: these thinkers did not have much interest in moderation, which they regarded as a weak and insignificant virtue, incapable of quenching their thirst for absolute, authenticity, and adventure. This should come as no surprise as many are usually enthralled by allegedly strong virtues—courage, prowess, fearlessness, and so forth—which are seen as incompatible with moderation. These are the virtues of the powerful, those who lead and govern, the state builders, the “lions” of this world. For them, there is no limit to what they may do with the lives of others; everything seems permissible to them, even violence. Allegedly weak virtues are those practiced by ordinary, inconspicuous individuals, the “lambs” of the world, the poor and the humiliated ones. They do not make history; instead, the latter is made without them or, better said, above them.4

How are we to explain the general skepticism toward moderation? It may be useful to start with a commonplace. Moderation seems to be the touchstone of many contemporary democratic political regimes, since no regime can properly function without compromise, bargaining, and moderation, and the proper functioning of our representative system and institutions depends to a great extent on political moderation. And yet, among major concepts in political theory and history (justice, liberty, equality, natural right, or general will), moderation is unique in being understudied. As a virtue, political moderation finds itself in an awkward situation. On the one hand, it has rarely been examined as a self-standing concept, even if we have been familiar with the works of famous thinkers considered to be moderates such as Aristotle, Montesquieu, Burke, or Tocqueville; their ideas have rarely been seen as belonging to a larger tradition of political moderation broadly construed. On the other hand, moderation is one of those concepts that may suffer from semantic bleaching. Sometimes, it is used in a very loose or narrow sense that fails to adequately capture its political, moral, and institutional complexity. This happens, for example, when moderation is conceived only as a relative concept defining itself according to whatever forms of extremism it opposes or whatever the poles might be between which it seeks to carve a middle path. A similar situation arises when moderation is equated with a defensive posture or a philosophy for weak souls, une philosophie pour les âmes tendres, as Sartre once put it. Finally, moderation has sometimes been represented as an allegedly aggressive and coercive means of social control in the history early modern Europe.5

The conventional image of this concept accounts to a certain extent for this curious and confusing situation. Moderation often appears as an ambiguous virtue whose genealogy and history are too vague to be properly defined or analyzed.6 Not surprisingly, we tend to misrepresent or distort the true meaning(s) of moderation, often regarded as the virtue of tepid, middling, shy, timorous, indecisive, and lukewarm individuals, incapable of generating heroic acts or great stories. Sometimes, moderation is desired not as a good in itself but mostly for its consequences, including the control of one’s desires, self-mastery, and harmony of the soul. In the first book of The Republic, for example, Plato showed the limitations of this narrow view of moderation embodied by an old and respectable character, Cephalus.7 His moderation in old age, a time of freedom from the domination of appetites, was a weak virtue that relied only upon the “release from a bunch of insane masters” (329d), suppression of desires, and faithful obedience to custom and tradition. This type of moderation appears as an obstacle to the pursuit of a free and happy life rather than a means to it. To make things more complicated, sometimes we may even need to abandon moderation for a while. There are, in fact, goods and values that are more valuable, at least for a certain time, than moderation, and we may have to act sometimes with immoderation in order to achieve necessary reforms, even if such courses of action might be criticized as radical or uncivil. As such, moderation challenges our imagination and appears as a fuzzy concept that defies universal claims and moral absolutes and is very difficult to theorize in the abstract (unlike, for example, justice or rights).

Lately, there has been a slight revival of interest in moderation that should not go unnoticed. Harry Clor (2008) analyzed moderation as a political, personal, and philosophic virtue, while Peter Berkowitz (2013) and Paul Carrese (2016) made a strong case for linking conservatism and political moderation viewed as a constitutional imperative. Ethan Shagan (2011) argued that the ideal of moderation (used to describe a wide variety of positions from that of the Church of England to the Conformists and Puritans) functioned as an ideology of control and as a tool of social, religious, and political power in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England. William Egginton (2011) discussed various aspects of religious moderation, while Julien Boudon (2011) traced briefly the history of the idea of moderation and ended with a few comments on the relevance of this virtue for contemporary French politics. Finally, in the pages of the New York Times, David Brooks has courageously defended political moderation as an indispensable virtue that might help us effectively tackle some of the most pressing issues we are facing today in an age of increasing ideological intransigence. To all this, one can add the passionate defense of Centrism put forward by John Avlon (2004 and 2014), whose work complements the detailed analysis offered by Geoffrey Kabaservice (2012) who documented the trend toward immoderation within the GOP in the last five decades. Finally, a special issue of the Sociological Review (2013) was devoted to the “sociologies of moderation” and brought together scholars from different fields who explored difference aspects of moderation. This issue was ably edited by Alexander Smith who has been studying the activism of grassroots moderates in Kansas, a state often seen as incompatible with political moderation.8

A Fighting and Civil Virtue

What is then the mentality of those who put moderation first? Moderates share a steady preoccupation with political evil and seek to avoid the extremes of cruelty, suffering, anarchy, and civil war. They tend to keep the lines of dialogue open and reach out to their political opponents in order to preserve the fundamental values of their communities. They do not see the world in Manichaean terms that divide it into forces of good (or light) and agents of evil (or darkness). They refuse the posture of prophets, champion sobriety in political thinking and action, and endorse an ethics of responsibility as opposed to an ethics of absolute ends. Sometimes, this involves significant personal risks and costs, including serving time in prison. If we are to look for a single word to characterize many (though not all) political moderates, then they might be described as trimmers who seek to adjust the cargo and trim the sails of the ship of the state in order to keep it on an even keel. Although their adjustments may be small and unheroic at times, they are often enough to save the state from ruin. In many respects, moderates are similar to the courageous tightrope walkers who must always be extremely careful to maintain their balance and sense of direction.

As a fighting creed, moderation is a combination of prudence, commitment, and courage far from the image of a lukewarm and indecisive mean between extremes with which it is often equated.9 The intellectual trajectories of the thinkers discussed in this book confirm this point. Theirs was a bold form of moderation that proves that Nietzsche was wrong when dism...