![]()

Chapter 1

How to Read

Cædmon’s miraculous gift of song is one of the best-known anecdotes from Anglo-Saxon England. We usually understand the episode that Bede relates in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People as a story of origins, celebrating the beginning of religious poetry in the vernacular language shared by Cædmon and Bede. Scholars have also taken it as another kind of originary text because of what it reveals about the oral composition of Old English poetry.1 What has received far less attention are the roles played by secondary actors in the drama. Cædmon, who was a peasant laborer attached to the monastery at Whitby, “had lived in the secular habit until he was well advanced in years and had never learned any songs. Hence sometimes at a feast, when for the sake of providing entertainment, it had been decided that they should all sing in turn, when he saw the harp approaching him, he would rise up in the middle of the feasting, go out, and return home.”2 Many things remain obscure about this feast on the fringes of the monastery and the characters on the margins of the story. What kinds of songs or poems were the farmhands singing? Did they include women and men? Did everyone play the harp? Were the songs long or short? Old or new? Did they draw from Germanic legend? How many might each person know? Were all the songs memorized, or were any singers talented enough to improvise?3 Even if time has erased any hope of answering these questions, our glimpse of these singing farmhands in seventh-century Northumbria is revealing in two respects. First, although the farmhands supply necessary background information for the narrative, Bede can afford to allude to them briefly because, it seems, their ability to entertain themselves was so commonplace that it passes almost without comment. With one notable exception all of them (omnes) know how to sing. Yet that widespread skill deserves no more attention than the ability of Abbess Hild’s scholars at Whitby, at a later moment in the story, to paraphrase biblical stories. Of course they could. What Bede singles out as noteworthy is the fact that Cædmon could live so long “without ever learning anything about poetry” (nil carminum aliquando didicerat). “I do not know how to sing,” he explains twice in his dream (nescio cantare and cantare non poteram), as if expecting the incredulous answer, “How could that be? How could anyone not know how to sing?” Second, if we extend this vignette of festive singing to the larger population of Anglo-Saxon England, it provides a crucial context for the reception of the poetry after it was written down. From a lifetime of hearing, recalling, and reciting alliterative verse, Anglo-Saxons who read the poems in manuscript, as well as the audience hearing those poems read aloud, came to the task with an intimate knowledge of that verse form’s conventions. It was a skill that extended up and down the ranks of society, both religious and lay. People like the pre-miracle Cædmon were the exception and not the rule. Yet even Cædmon, as ungifted as he was, spent years listening to such songs, if we accept the details of Bede’s narrative, because he would remain seated at the feast until the harp came around to him. Only then did he get up to leave.

Another character marginal to Bede’s story but central to this book’s topic is the reeve, whom Cædmon told about the gift he received. “The reeve,” Bede gives as a matter-of-fact detail, “took him before the abbess.”4 Are we to understand that the reeve recognized that something extraordinary had taken place? Very likely, according to the logic of the narrative, because why else would he bother the abbess Hild with a farmhand reporting a dream in a cowshed? Bede does not say whether Cædmon recited his nine-line poem to the reeve, who functions as a nameless intermediary, in some respects little more than a plot device to move Cædmon from one setting to another, but without his intervention Cædmon’s career as a religious poet would have been stillborn. If we take the narrative at face value, the reeve is an anonymous hero of the story, because he recognized that what happened to this peasant was extraordinary enough to merit an audience with the abbess. Hild was no ordinary abbess, either, because she was connected by birth to the East Anglian and Northumbrian royal houses and was the head of a double monastery (monks and nuns living in separate communities within the same foundation) famous for its scholarship and piety. In the larger structure of The Ecclesiastical History, the story of Cædmon is placed within a section that celebrates the virtues of the abbess Hild. More immediately it shows that competence in poetry was shared from peasants to royalty.

Finally, my survey of the background characters of Bede’s story of Cædmon moves to Hild’s scholars (doctores), who test the validity of Cædmon’s account by telling him a pious story and ask him to turn it into poetry.5 He returns the next day with “excellent verses” that vindicate the miracle. After entering the monastery he learns more stories from scripture from the scholars, which he turns into such excellent poetry that he “turned his instructors into auditors” (doctores suos uicissim auditores sui faciebat). The Old English translation of Bede’s Latin goes further and says that these instructors (lareowas) did not merely listen but “wrote down what he uttered” (æt his muðe wreoton).6 This small detail, inserted in the translation over 150 years after Bede and 200 years after Cædmon, is likely the invention of a well-intentioned translator or scribe, but there is a logic to it that would have appealed to a later audience. They might surmise that at some point, perhaps as early as the time of Cædmon, some scribes began writing down the vernacular poetry using the alphabet normally reserved for Latin. The brief mention of wreoton makes it sound straightforward, but it conceals a tangle of questions, most importantly: How did early scribes trained in Latin adjust their conventions to meet the task? Transcribing the sounds of Old English using letters from the Latin alphabet would require some innovation for the vernacular sounds not found in Latin, such as the first and last sounds of the English word “with,” but it was a manageable task. Early glosses like the Épinal manuscript, dated to the last decades of Bede’s life, already show a consistency in representing the sounds of Old English that suggests “a settled spelling system.”7 For poetry a more complicated question facing the scribes would be how to format the verse: Should they employ the conventions of lineation developed for Latin poetry? Invent an alternate system? What punctuation to use? The earliest transcriptions of Cædmon’s Hymn appear in continuous lines with almost none of what we could today consider verse formatting or punctuation.8 Cædmon’s nine lines would not pose much of a challenge for an Anglo-Saxon reader’s comprehension, but what about longer narratives and complex syntax?9 The surviving corpus suggests that the conventions for transcribing Latin and Old English poems evolved in different directions. By the second half of the tenth century even the scripts used for the two languages diverged, “one for Latin derived from caroline minuscule and one for the vernacular derived from Anglo-Saxon minuscule.”10 Equally relevant for this study, at this same time other visible cues for reading diverged: the use of capitals, punctuation, lineation, and various uses of space on the folio.

It was not inevitable that the conventions should move in different directions for the vernacular and Latin. It would have been a simple task for Anglo-Saxon scribes to carry over some of the conventions from Latin verse—such as the use of space, capitalization, and punctuation—to aid the reader. They were not lacking a precedent: Anglo-Saxons had already borrowed Latin words into the Old English lexicon and had loaned Germanic runes to the Latin alphabet. With such commerce already established, the apparent indifference to an available fund of visible cues is even more intriguing.

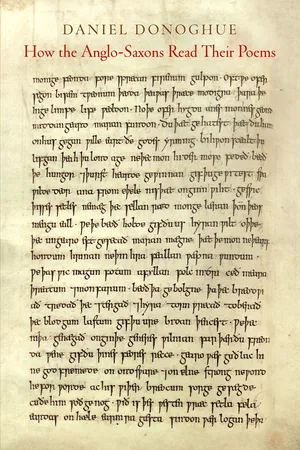

Almost all extant Old English poetry that has come down to us is written out across the sheet of vellum, from margin to margin, as if (it is often said) it were prose. There is an unintended irony, however, in invoking prose as a comparison to this way of writing, because the conventions of poetry are older, formulated centuries before the poems were ever committed to writing. Old English prose could emerge only after the introduction of writing, which means that very few Anglo-Saxons before the middle of the ninth century would know what their vernacular prose looked like.11 The prose of any language is not merely a transcription of ordinary spoken discourse, although it bears a resemblance to it. Poetry, on the other hand, especially when it derives from an oral tradition such as that of Old English, can be written æt muðe because its conventions can survive what our age of word processors might call an unformatted transcription. Nevertheless, in the surviving manuscripts the margin-to-margin writing of verse does bear a superficial resemblance to the prose of many periods and languages, simply because it lacks the now-familiar conventional lineation, in which each line of verse is written out separately, leaving a ragged right-hand margin. In manuscript the poems do not look at all like printed verse we are accustomed to reading, whether that is one of the recent editions of Beowulf or the hundreds of poems from many centuries published in classroom anthologies. Electronic reproductions and photographic facsimiles in our Old English editions and textbooks have made the presentation on the folio familiar: the script running from margin to margin with no distinct spacing at the end of sentences or verse lines; the sparse punctuation; some words separated into morphemes; phrases run together as a single “word”; few capitals, few paragraph breaks, no question marks, no quotation marks. The editorial challenge posed by the apparently unsystematic conventions is exacerbated by scribal errors and damaged manuscripts.

One school of thought concerning the sparseness of visual cues in manuscripts of Old English poems, most of which were transcribed within decades of the year 1000, is that it is not quite systematic yet not quite random. In speaking of the punctuation for the Exeter Book riddles, for example, Craig Williamson concludes, “Thus, points are used for a number of things in the Riddles; they may carry metrical, rhetorical, syntactic, or paleographical significance. Normally they are significant in at least two categories. The punctuation is certainly not systematic nor is it random. Where a point might be indicated by more than one category of significance, there the scribe has the strongest tendency to point.”12 The scribes’ practice is regular enough to tantalize, in other words, but sporadic enough to frustrate anyone looking for a consistent pattern. Its inscrutability has made it easy to neglect; some editions of Old English poems itemize the manuscripts’ capitals and accent marks but dismiss the punctuation with passing generalizations.13

For most medievalists the manuscripts are not our first or dominant experience of Old English poetry, as the Introduction mentions. We first encounter it in meticulously prepared editions that transform the words and fragments into pairs of half-lines organized into sentences and paragraphs that adopt modern conventions of punctuation and capitalization.14 An indisputable result of these changes has been to make the poetry look familiar, even if, as beginners, we might not make sense of the words without effort. At some point (usually early along) we learn about the manuscripts, but by that time our sensibilities about the visible presentation of Old English poems have already been shaped by the printed editions, reinforced by the layout of published poems in general. The extent of editorial in...