- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

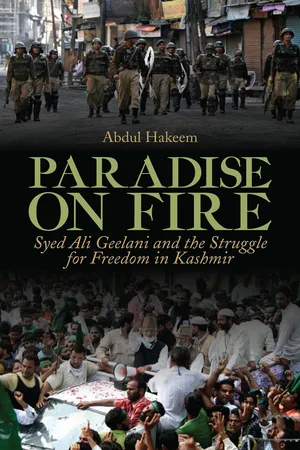

Paradise on Fire is the story of the struggle for national liberation of the people of Jammu and Kashmir, spearheaded by Syed Ali Shah Geelani. This political biography of Kashmir’s leading freedom fighter reveals the true horror of the Kashmir dispute, the dynamics of this historical struggle for self-determination, and Geelani’s huge contribution in leading this search for liberation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Paradise on Fire by Abdul Hakeem in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Indian & South Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE DISPUTE

TARUN VIJAY is a Rashtriya Swyamsevak Sangh (RSS) ideologue and an MP representing the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP). A former editor of India’s leading English daily The Times of India, he pronounced in his editorial of 31 May 2008 that ‘people who remember their past have a future.’ Led by Geelani, Kashmiris have proven beyond doubt that they remember their past.

1.1 Map of Jammu and Kashmir

Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) occupies some 222,870 square kilometres in the strategic, extreme northwest of the Subcontinent next to Afghanistan (northwest), the Sinkiang-Uighur region of China (north), Tibet (east), the Indian states of Himachal and Punjab (south), and the Pakistani provinces of Frontier and Punjab (west). No census has been carried out in J&K since 1981; its population is estimated at 12.54 million, with Muslims the largest group. The Kashmir valley itself is not very long – about 170 kilometres from Banihal in the south to Kupwara in the north, and about 80 kilometres from Gulmarg in the west to Kangan in the east. The Jhelum river flows through the valley, first northward, then bending south-west before crossing through the Uri gap into Pakistan-administered Kashmir (PaK). The Jhelum makes the Valley extremely fertile; the main urban centres are situated on its banks.

The Valley is densely populated, with semi-urban clusters of mostly wooden houses. It is not completely flat – there are a series of outcrops called karaves, the largest being the one on which Srinagar airport is built. The karaves are cut by gullies, in parts uncultivable and thickly wooded – terrain perfectly suited for guerrilla warfare. This topographical advantage was highlighted by Syed Salahuddin – Supreme Commander of Hizbul Mujahideen (HM), the largest Kashmiri armed group fighting Indian occupation forces – when I asked him how long militants could stand up to the Indian military.

Rinchan, a Buddhist ruler of Kashmir embraced Islam in 1320 at the hand of Syed Bulbul Shah. Persian scholar and missionary, Sayyid Ali Hamadani also played a pivotal role in spreading Islamic values. Islam consolidated its hold during Shah Mir’s reign (1339–44). Independent Sultans ruled till 1586 followed by Mughals (1586–1753); and Afghans (1753–1819).

The era of Afghan rule was harsh and oppressive, with burdensome taxation and frequent Shia–Sunni riots. Thereafter, Kashmir became one of the roughly 584 princely states in India under the direct or indirect control of the British Empire. Gulab Singh was the ruler of an erstwhile Sikh kingdom. The British rewarded his neutrality during the first Anglo–Sikh war, by literally selling him the Kashmir Valley for Rs. 7.5 million. Thus, the Dogra dynasty was established on the betrayal of India’s freedom movement against British occupation. Salahuddin explained this further in an interview to an Indian news portal:2

In 1819 Maharaja Ranjit Singh conquered Kashmir, but his disorganized empire fell to the British in 1846 when they took control of Punjab. Kashmir was then sold to the self-titled Maharaja Ghulab Singh of Jammu for Rs 7.5 million under the Treaty of Amritsar.

Ghulab Singh also brought Ladakh, Zanskar, Gilgit and Baltistan under his control. A succession of [Hindu] Maharajas followed, marked by several uprisings by the Kashmiri people, of whom a large percentage was now Muslim. In 1889 Maharaja Pratap Singh lost administrative authority [over] Kashmir due to the worsening management of the frontier region. The British restored full powers to Dogra rule only in 1921.

Tavleen Singh, an honest and courageous Indian journalist, observed in her landmark book Kashmir: A Tragedy of Errors (1995), p.xiv:

Dogra rule was hated because Muslims, who constituted the majority of the population, were discriminated against in every way. […] Kashmiri Muslims with extremely low literacy levels were mainly landless peasants and craftsmen with almost no hope of bettering their lives.

Formal annulment of the Ottoman caliphate in 1924 led to popular agitations across the Islamic world. In India while the Hindu-dominated Indian National Congress (for its political reasons) supported the Khilafah movement, the ‘J&K government banned it.’3 Sir Albion Bannerji, appointed in 1929 to a senior post in the Council of the State of J&K, quit before his two years were up, commenting: ‘There is no touch between the government and the [largely Muslim] people, no suitable opportunity for representing grievances and the administrative machinery itself requires over-hauling from top to bottom…. It has at present no sympathy with the people’s wants and grievances.’4

The brutal Dogra autocracy triggered a revolt in 1931, which was ruthlessly crushed with 22 Muslims killed. Another eruption in 1946 against the Hindu ruler Maharaja Hari Singh led to the formation of a Muslim government-in-exile in August 1947. At an annual session of the National Conference in Sopore, India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was invited as a guest speaker. Addressing Kashmiri Muslims he conceded: ‘[the] Dogra government forced you to lead a subhuman existence.’5

Until Partition in 1947, Kashmir retained its historic links with Central Asia: the mail passed through normally; Russian Muslims came down through Gilgit to go on the pilgrimage to Makkah. Weakened after 1947, these ancient links are now ‘extinct’ (Frontline, 23 March 2012). Gandhi, speaking at Wah on 5 August 1947, affirmed that the will of the Kashmiri people was the supreme law in J&K, and that this was acknowledged by the Maharaja and Maharani themselves. He had read the so-called ‘Treaty of Amritsar,’ which was in reality a deed of sale; he fully expected it to be defunct in August 1947. Gandhi believed that sheer common sense made it obvious that the will of the Kashmiris should decide the fate of J&K, and the sooner it was done, the better. (cited in The Indian Express, 23 August 2000)

Under the terms of Partition, all princely states under British rule had to accede to India or Pakistan, except that to do the latter (a) the majority population of the territory had to be Muslim and (b) its borders contiguous with the territory that would become Pakistan. It happens that (as noted in prominent Indian magazine, The Outlook (9 July 1997)): ‘Most people of Jammu and Kashmir were Muslims, the ruler was Hindu. Its transport links were mainly with the areas that would become Pakistan, the rivers which transported its timber flowed in the same direction […] the case to include it in Pakistan was hard to rebut.’ For all that, the Indian governments argue that the 1947 Indian Independence Act did not envisage the division of princely states on the basis of majority subjects’ religion.

The wishes of the majority Muslim Kashmiris were ignored by the Hindu ruler of J&K who hit back hard at protests. According to Geelani,6 ‘In just a few weeks, in late 1947, Dogra forces and Hindu chauvinists in Jammu killed some five lakh Muslims.’ Muslims in the Poonch district rose up against the Hindu rulers. In his book Kashmir: The Unwritten History, Christopher Snedden, an Australian author and academic specializing in South Asian studies, ‘dismisses India’s claim that Pakhtoon tribesmen [from the Frontier province] stoked the Kashmir conflict in October 1947.’ He adds that ‘there is the secret correspondence between Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel making it clear that they were aware of what was going on [i.e. it was a local uprising].’7

When Muslims from the Frontier region came to help Kashmiri Muslims, the Maharaja fled his capital, Srinagar, and called in Indian government troops, accepting the condition that he sign the instrument of accession to India. Aware that such a decision made under duress would be of questionable legal weight, the Indian government clearly agreed that the accession was provisional and subject to ‘reference to the people’.

Captain Dewan Singh was the Assistant of Maharaja Hari Singh. In a 2 June 1994 report in the Indian daily, The Telegraph, Captain Singh described the momentous event on the eve of 26 October 1947. The seventy-five-year-old Assistant of the then ruler said the atmosphere was choked with tension as he waited in Jammu palace outside the room where the Maharaja signed the instruments of accession with India. He recalled: the last viceroy of British India Louis Mountbatten had advised Maharaja Hari Singh to join Pakistan in the tense days leading to Indian independence. Being a Muslim majority region, Lord Mountbatten reasoned, it made sense for Hari Singh to opt for Pakistan. But Kashmir’s ruler was staunchly pro-India. He was to meet Lord Mountbatten the following day for further consultations. But he cried off, pleading ill health, says Dewan Singh. And the meeting, which would definitely have changed the Subcontinent’s history, never took place.

The accession of Kashmir to India is analogous to the annexation of Texas by the USA. When Mexico separated from the Spanish Empire and became an independent republic, Texas was an integral part of it. Later, Texas rebelled, declared independence from Mexico and had its new status recognized by the USA and the major powers of Europe. Threatened by incursions from Mexico, the Texas governement asked the US to annex it in 1844, a ‘request’ approved by the US Congress in March 1845 and followed by the deployment of American troops to the boundary of Texas. The government of Mexico at the time protested strongly and suspended diplomatic relations. This history (along with other factors discussed later in this book) makes continued US support for Indian occupation of J&K more likely.

Since Muslims from the Frontier had taken a part of the J&K state (the part now known as PaK), India brought the issue to the United Nations (UN) in January 1948. India accused Pakistan of sending ‘armed raiders’ and urged the UN to compel Pakistan to withdraw. According to Salahuddin: ‘The British government at that time [of Partition] played a very bad role. Kashmir is the unfinished agenda of 1947. Even today there is no legal succession document and that is why India lost its case in the United Nations.’8

After UN intervention, armed hostilities halted at the Ceasefire Line or Line of Control (LoC). India assured the UN that, following the withdrawal of ‘raiders’, it would hold a plebiscite. Pakistan challenged Kashmir’s accession, accusing India of using ‘fraud and violence’ in this process, and offered a plebiscite under UN supervision to settle the dispute.

On 21 April 1948, the UN Security Council (UNSC) passed a resolution ordering (a) ceasefire, (b) withdrawal of outside forces from J&K and (c) a plebiscite under the control of an administrator nominated by the UN Secretary-General. A UN Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) was formed to work out the mechanism for plebiscite. After a (never explained) delay of 76 days, UNCIP members arrived in the Subcontinent on 7 July 1948 despite the UNSC instruction ‘to proceed at once’ and enter into intensive negotitions with both governments at the highest level towards formulating an agreement to a ceasefire and synchronise withdrawal of all regular Pakistani forces and the bulk of Indian forces (constituting a truce between the two sides) and reaffirmation that ‘future status of the State shall be determined in accordance with the will of the people’. Thereafter:

On 13 August UNCIP adopted a Resolution, which is a draft agreement committing the Pakistan and India governments that the ‘future status of the State of Jammu and Kashmir shall be determined in accordance with the will of the people.’9

On 20 August, Prime Minister Nehru wrote to UNCIP Chairman stating that his government ‘have decided to accept the Resolution.’ On the basis of India’s understanding (stated in the letter) of several key terms of the Resolution, Pakistani Foreign Minister Zafrullah Khan sought ‘elucidations’ from UNCIP regarding its proposals and the explanat...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Images

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1. The Dispute

- 2. A Lifeline of Resistance

- 3. Neighbouring Lands and Peoples

- 4. Imprisonment and Writings

- 5. Kashmir’s Pandits and Its Integrity

- 6. Human Wrongs

- 7. Terrorists or Freedom Fighters?

- 8. Insurgency and Counter-insurgency

- 9. Elections and the Peace Process

- 10. The Kargil Fiasco

- 11. Ceasefire

- 12. The Hurriyat Split and Efforts towards Unity

- 13. Ailing but not Caving In

- 14. A Bilateral or International Issue?

- 15. The Bottom Line

- 16. Not the End

- Appendix

- Endnotes

- References

- Image Credits

- Index