- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Dr. Seddon has contributed an important and fascinating chapter to the modern history of Britain."—David Waines, emeritus professor of Islamic Studies, Lancaster University, UK

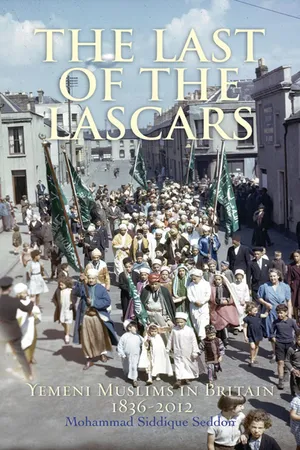

Originally arriving as imperial oriental sailors and later as postcolonial labor migrants, Yemeni Muslims have lived in British ports and industrial cities from the mid-nineteenth century. They married local British wives, established a network of "Arab-only" boarding houses and cafes, and built Britain's first mosques and religious communities.

Mohammed Siddique Seddon is lecturer in religious and Islamic studies at the department of theology and religious studies, University of Chester, England.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Last of the Lascars by Mohammed Siddique Seddon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

YEMEN: A BRIEF HISTORY OF ARABIA FELIX

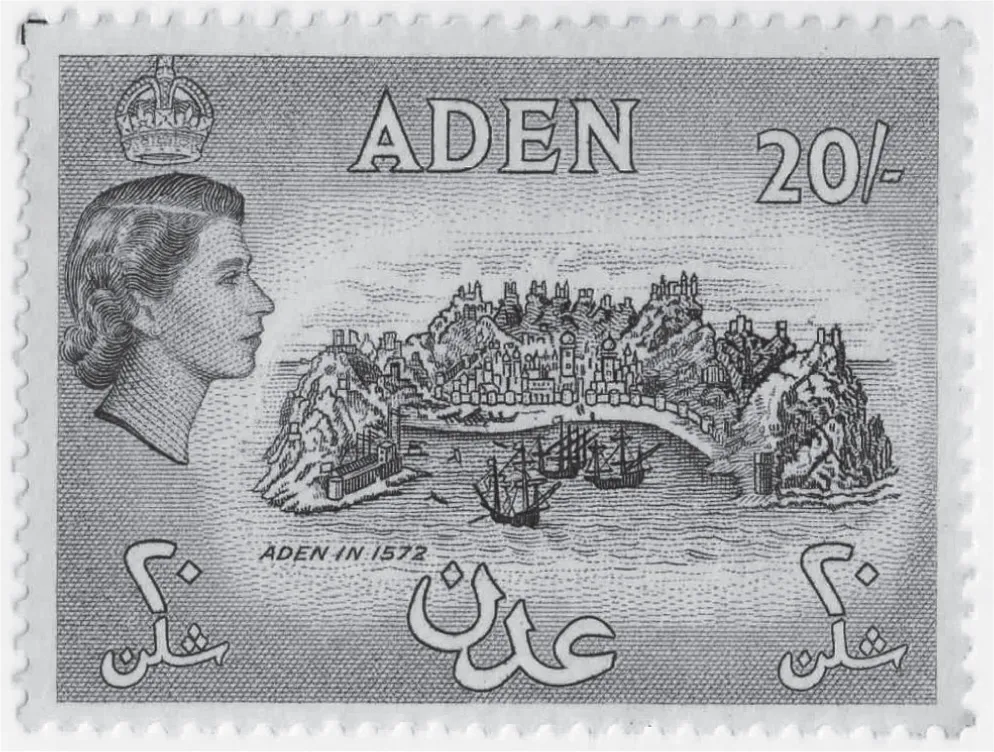

THE PORT OF ADEN at the tip of southern Yemen has been historically described as the ‘gateway to China’ largely because ancient Arab mariners used the port as a midway point in the maritime trading routes between the eastern coast of Africa, the Mediterranean, via the desert caravan routes, and India, China and Malay.1 The oceanic ‘super highways’ created by Yemeni and Omani merchant seamen ensured that Arab colonies were well established in East Africa and India long before the advent of Islam in the seventh century CE. In the Yemeni context, these important trade routes were traditionally dominated by the two ruling tribes of the Kathīrī and Qu˓aytī emanating from the fringes of Ḥaḍramawt in al-Ruba˓ al-Khālī (‘The Empty Quarter’) desert of the southern Arab Peninsula. Ancient histories of Middle Eastern civilizations make very little reference to Yemen, focusing instead on the wonders of Babylon and Pharoanic Egypt. The general absence of any narrative of ancient Yemen, however, cannot deny its unique importance in the economic development of the region from around 2000BCE until 700CE. In this period, Yemen was a flourishing area ruled by a number of important kingdoms who advanced the region’s prosperity and technological development. The pre-Islamic civilizations of Awsān, Ḥaḍramawt, Ḥimyar, Ma˓īn, Qatabān and Saba’ were ancient kingdoms whose histories shaped the very nature of what we know today as Yemen.2 It is only their remoteness in relation to modern population centres that have made the abandoned desert ruins of these previous civilizations the subject of myth and legend.

In more recent times, Yemen’s virtual encapsulation, as a result of almost a thousand years of Zaydī Imāmate-rule, cut the region off from the rest of the world, resulting in a further ignorance of the country’s rich and epic history. It is only in the last 200 years that Western explorers, often at great personal risk, have been able to penetrate Yemen’s unforgiving landscapes of remote and rugged mountains and vast barren deserts to reveal many of its important archaeological sites and lost ancient settlements. Modern excavations of these now isolated sites have revealed not only their former glory as centres of advanced civilization, but also their key role in the extremely lucrative trade in rare spices and expensive incenses. The abandoned ancient trading entrepôts were vital to the commodities and rites of the ancient world. In Pharoanic Egypt and ancient Babylon, the use of frankincense and myrrh in the religious rituals of mummification and the employment of aromatic gums as precious commodities used in medicines, cosmetics and foods was acknowledged across the ancient world. Egyptian demand for these rare goods established permanent trade routes to the incenseproducing areas of Ḥaḍramawt and Ẓufār in Southern Arabia. This lucrative trade was then further extended to later Greek and Roman civilizations to the north of Arabia via the vast camel caravans of the incense routes. This international trade enabled the regional kingdoms and their capitals to flourish that saw the establishment of a number of important seaports including Qānā in the south of Arabia and Gaza in the north.3 Economic cooperation was vital to all the kingdoms of the region and, despite often on-going hostilities between various regional sovereignties, protection for trade caravans was ensured through a system of ‘commissions’ or taxes from the merchants in return for safe passage through tribal territories across the deserts and highlands. However, protected travel could only be assured where traders adhered strictly to a prescribed and widely recognized route and any breaches could often result in the penalty of death.

1.1 – A British stamp from the Aden Protectorate published in the 1960s displaying an early etching of the port.

Whilst relatively little is known regarding the administration and organization of the various ancient kingdoms of the region, archaeological evidence and research suggests that the majority were polytheist, with a number of ancient temples and places of worship dedicated to astrological deities such as the sun, the moon and other celestial entities.4 Further, the excavation of burial sites also indicates a belief in an afterlife by the presence of a number of personal possessions included in many graves. Archaeologists also interpret the gradual development of simple stylized sculptural forms into intricate three-dimensional figures, complete with individual features, as suggestive of the wealth and influence generated through the highly profitable incense trade that exposed these relatively isolated societies to more advanced civilizations. The distinctive and fairly rapid shift from simple geometric designs to greater developed floral shapes and patterns indicate clear Hellenistic influences. Architecturally, the design of the original temples, constructed of rectangular buildings flanked with square shaped columns, is contrasted with the later buildings which appear to replicate the hallmarks of Greek and Roman architectural motifs.

ANCIENT RULERS AND KINGDOMS

Although historians generally refer to the overarching ancient civilization of the region as Sabean, the kingdoms of southern Arabia were largely contemporaneous and did not succeed each other. Rather, different kingdoms reached their civilizational peak at different times. For example, by the third century CE, the Ḥimyarite kingdom exercised its hegemony over the neighbouring kingdoms of Saba’, Dhū Raydān, Ḥaḍramawt and Yamnat and, a century later, Ḥimyarite ascendancy included rule over the Bedouins of the highlands and lowlands, forming the first political unification of southern Arabia under a single ruler. Before Ḥimyarite ascendancy, the Sabeans had dominated the region for well over a thousand years, creating a kingdom whose influence reached far beyond tribal tributaries. Equally, the people of the Ma˓īn kingdom in the north of the region were economic stalwarts whose commercial exploits and interests reached as far as the Nabatean city of Petra in central Arabia and several countries around the Mediterranean. However, it was only the kingdom of Ḥaḍramawt that produced the muchneeded luxury commodity of frankincense, from the Dhofar region, which was shipped through the ancient port of Qānā, today known as Bi’r ˓Alī, thereafter transported overland through Shabwah.5

In the ancient world, the consumers of the expensive incenses were never informed of their precise origins, hence the legends and myths that surround the early medieval spice and incense trade. For example, Heredotus wrote that incense growers lived in isolated groves and were forbidden marital relations with women or to attend funerals. He also claimed that the mythical groves which produced the precious incense were guarded by winged serpents. But such fables were probably largely the result of overzealous Yemeni incense merchants who wished not only to preserve the high prices sought for their wares, but also to protect the sea routes they had mastered to India and China by learning to negotiate the monsoon winds.6 The ancient sea routes brought in further expensive luxuries such as spices and silks which all passed through Yemeni ports on to camel caravan routes through Arabia into Greek and then later Roman domains. So fruitful were Yemeni merchants in the trade of precious commodities, that the Romans believed that the Arabian Peninsula was the producer of all such expensive items, prompting them to describe the Yemen as Arabia Felix (‘Fortuitous Arabia’). But the exotic and mysterious image of Arabia, cultivated by the Romans, overlooked the harsh realities of life in the region in which the majority of the population were held in virtual serfdom, working the irrigated foothills of the highlands in the production of much-needed agricultural produce. Evidence of this early sophisticated agricultural society is best seen in the ancient remains of the huge rock monoliths of the former Ma’rib Dam. These now strange free-standing structures are all that remain of the colossal wādī (valley) sluices that trapped the rainfall running down the valleys, forming a complex irrigation system constructed by the ancient Sabean civilization that is believed to have irrigated more than 16,000 hectares, producing food for an estimated 300,000 people.7

The Ma’rib Dam is a legend that even finds references in the Qur’ān (Sūrah 27, Al-Naml and Sūrah 34, Saba’) and is linked historically to the Old Testament Queen of Sheba (or, Bilqīs), who was said to have visited King Solomon’s (Sulāymān) court in ancient Palestine (10 Kings: 1–3, Chronicles: 1–2). Scripture offers only sketchy descriptions of the events and no absolute narrative exists as to the exact detail of the ancient queen, her epic journey to Solomon’s seat and the details of her kingdom. Archaeological excavations of these ancient Sabean sites are slowly beginning to offer further evidence of this once great civilization. The collapse of the Ma’rib Dam in the fifth century CE, and its ill-fated restoration that resulted in its ultimate collapse 100 years later, is seen as the catalyst for the demise of the Sabe...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Chronology

- List of Illustrations

- Transliteration Table

- Foreword

- Prologue

- 1. Yemen: A Brief History of Arabia Felix

- 2. From Aden to ‘Tiger Bay’, ‘Barbary Coast’ and ‘Little Arabia’

- 3. First World War: From Sacrifice to Sufferance

- 4. Interwar Period: Shaykh Abdullah Ali al-Hakimi and the ‘Alawī Ṭarīqah

- 5. Post-World War Two Migration, the Muwalladūn and Shaykh Hassan Ismail

- 6. Shaykh Said Hassan Ismail and ‘Second Wave’ Migration

- 7. Becoming Visible: The Emergence of British Yemenis

- Epilogue

- Endnotes

- Glossary

- Picture Credits

- Bibliography

- Index