![]()

1

Broadcasting Ourselves

In May 2012, I was sitting on my sofa browsing the internet when I stumbled on a website showing a live feed of a StarCraft 2 computer game tournament taking place in Paris. In esports competitions, professional players compete in a formal tournament setting for prize money. Having done research and written a book on esports, I was familiar with game broadcasting attempts over the years, but this production particularly caught my eye. The event was taking place at the beautiful Le Grand Rex concert hall, and camera shots of an energetic, cheering audience of over two thousand people were interspersed with live feeds of the game competition. The strange world of StarCraft, populated and fought over by human Terrans, otherworldy Protoss, and creepy insectoid Zergs, shared screen time with the faces of the players, commentators, and audience that filled the large theater. Yet there was also another set of spectators—ones solely participating online. Along with thousands of others around the world, I was watching this match in real time over the internet. On our screens, alongside the video piping out from Paris, a chat stream (an old-school Internet Relay Chat [IRC] channel) flowed by with hundreds of people talking to each other about the event, and cheering through text and emoticons.

As someone who has not only studied gaming but also has roots in internet studies, virtual environments, and synchronous computer-mediated communication, my research ears perked up. What caught my attention was not only the spectatorship; it was also the forms of communication and presence among broadcasters and audience, both on-site at the venue and distributed throughout the network. I was intrigued by the experience as a media event. This show was being broadcast to a huge global audience, and as I came to learn over the course of that night, was being talked about in a variety of other online spaces such as Twitter. I had my television on in the background, but soon turned the volume down. This game “channel” being broadcast on my laptop captured my full attention. It was immediately clear to me that I needed to explore this space more.

That feeling—that I was not watching alone but instead alongside thousands of others in real time—was powerful. It was a familiar, resonant experience for me. I’ve long loved television, especially live content, and even as a kid I felt its pull. I remember getting a small black-and-white television in my bedroom as a preteen, and staying up late to watch Saturday Night Live and tap into an adult world I didn’t have access to at that age. Breaking news frequently had the effect of helping me feel an immediacy of connection with a larger world. My father always either had on the evening news or a sports broadcast, and our family typically had the TV on from late afternoon through to bedtime. Beyond live shows, we constantly had on cartoons, sitcoms, and procedurals, and rather than going to the theater, watched most movies through it. The TV was an object our family shared and gathered around. We kept it on constantly. Much like Ron Lembo’s (2000) account of “continuous television use” (including his personal reflections on how TV was situated in his own working-class home), my personal and social experience of television has ranged from the mundane to meaningful.1 Sometimes it held my full attention, while at other moments it was simply background noise, offering a welcome ambient presence.2 Television was not only a presence in my family’s life; it connected me to the outside world, entertained and informed me, offered material for conversations with others, gave me broader cultural waypoints, and sometimes just kept me company.

This relationship with television is not, of course, unique to me. Scholars over the years have documented the profound role it can have in our lives—from politics, ideology, and mythmaking to socialization—structuring our domestic lives and mundanely offering its presence.3 Unlike some television scholars, I never undertook this object of my affection and attention as a site of research. It simply was. But that night, watching the game live stream and audience engaged alongside me online, I paused. Though I have remained a television viewer my entire life, like many I also came to spend a lot of time online and in gaming spaces. This broadcast seemed to weave together all these threads at once: it was an interesting collision of the televisual, computer games, the internet, and computer-mediated communication. Its vibrancy as a live media product, both like TV and yet very much something else, was captivating.

Within esports—formalized competitive computer gaming—there has long been a quest to see gaming make the shift to television, despite many bumpy attempts over the years. The hope has been that if it could get into broadcast, not only would its legitimacy be signaled, but the audience for it could grow significantly. In my prior analysis of that industry, I briefly discussed the use of streaming media to broadcast competitive play, and remarked on how “social cam” websites like Justin.tv and Ustream were being utilized by gamers (Taylor 2012). These sites were typically hosting people simply streaming their everyday lives via webcams, offering amateur talk shows or even mundane “puppycam” channels where viewers could watch litters of sleeping newborn dogs. Yet some gamers were also gravitating to these sites, pushing their personal computers to crank out live video of their play to whoever wanted to tune in and watch. Though they didn’t easily fit in the model of expected use of the sites, they were there pressing it for their own purposes.

Things have since changed quickly in the world of live streaming. Twitch, a broadcast platform dedicated to gaming that spun off from the social cam site Justin.tv in June 2011, has in a handful of years dramatically reshaped the landscape.4 By 2017, the site boasted 2.2-plus million unique broadcasters per month with 17,000-plus members in the Twitch Partner Program and 110,000 “creators” in the Affiliates Program—content producers that receive revenue from their streams—and about 10 million daily active users (Twitch 2017b, 2017c). It hosts a wide variety of games from various genres. Major esports tournaments will, typically over the course of a weekend, reach millions of viewers. Variety streamers, those broadcasters who play a range of games, can pull in thousands of viewers per session. Though a thin slice of broadcasters get the lion’s share of the audience and smaller channels often only host a handful of viewers, browsing the site you can find hundreds of channels at any time of the day.5 Though most major televised sports events still trump esports live streaming in terms of audience size, and specific numbers for any single session should be taken with some caution, the overall growth of live streaming as a medium for new forms of broadcast and game content is indisputable.

Twitch is certainly not alone in helping build esports; other platform companies such as YouTube or Facebook, organizations like the Electronic Sports League (ESL), DreamHack, PGL, and Major League Gaming (MLG), and game developers such as Riot, Valve, and Blizzard have all tossed their hat into the live streaming ring by producing and/or distributing broadcast content. A generation of game consoles, the PS4 and Xbox One, both launched in 2013–14 with functionality to support broadcasting your play through live streaming. And traditional media companies such as Turner have gotten into the mix via the ELEAGUE tournament, which appears on both traditional cable and Twitch. Hours and hours of gaming content are now produced and consumed every day, 24-7, via live broadcast over the internet.

Though speaking about “waves” in any domain risks obscuring the threads of continuity or earlier experiments that never caught on, it can be helpful in broad strokes to describe esports this way, especially for those who may not know much about gaming. The first wave (the 1970s and 1980s) was anchored in arcades and around home console machines where the local dominated. The second wave (the 1990s through 2010) leveraged the power of the internet for multiplayer connections and a more global formulation of the competitive space. That period also witnessed the power of networking as a means to jump-start an esports industry—one that largely had its eye on traditional sports as its model. The third wave (starting around 2010) has at its core the growth of live streaming that takes the power of networking we saw earlier and powerfully combines it with the televisual. It is during this period that esports has become not just a sports product but a media entertainment outlet as well.

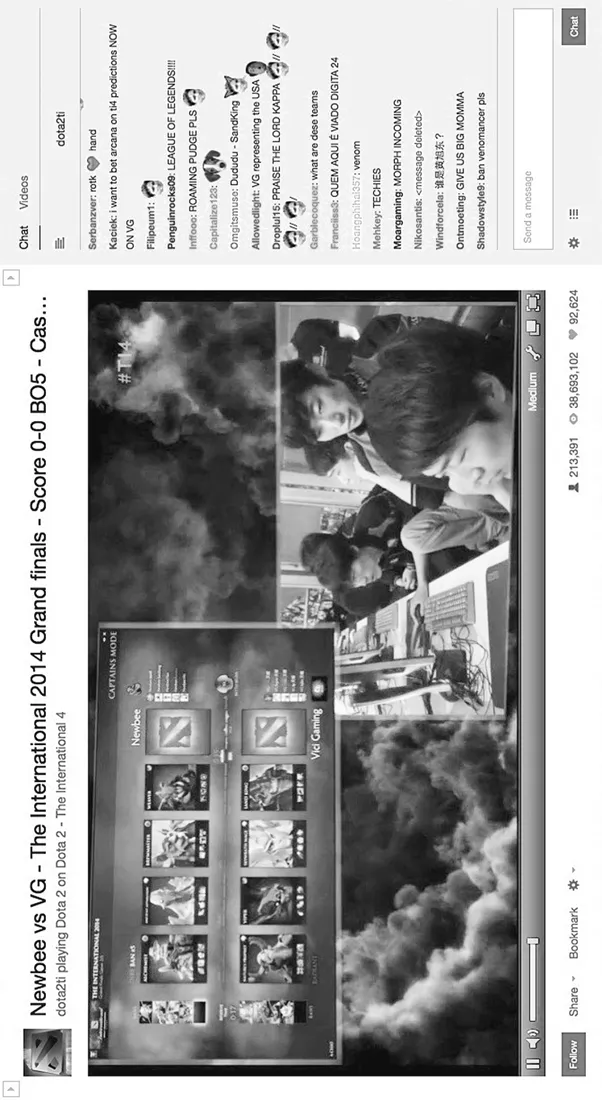

Live streaming offers professional esports players and teams opportunities to build their audience, brand, and incomes, while streaming their practice sessions—often straight out of their bedrooms. Tournaments are leveraging the medium to expand the reach of competitive gaming by building global audiences largely based online (see figure 1.1). Being an esports fan suddenly became much easier with live streaming.

FIGURE 1.1. The International grand finals, 2014. Teams selecting their match characters. The lower-right corner below the image shows the number of people currently watching (213,391), total views of the channel (38,693,102), and number of people who have specially tagged the channel to follow. The right side of the screen is a live chat window.

You no longer needed to download a game replay file, track down a video on demand (VOD) on YouTube and a niche site, or constantly search out tournament results after the event. Twitch hosted massive amounts of content, from practice time to tournaments. There you could also talk to fellow audience members, “follow” your favorite channels to receive notifications when broadcasters went live, and subscribe to channels for a monthly fee, which, among other “member perks,” would remove ads from the stream. With Twitch’s purchase by Amazon in 2014, “Prime” members eventually got additional benefits on the platform (such as free game content) if they linked their accounts.6 Having previously tracked the second wave of esports, the emergence of game live streaming illuminated for me how profoundly a televisual experience combined with the power of network culture could transform a nascent industry.

As I began spending more time on the site, however, I realized there was a much bigger project lurking. The growth of game live streaming wasn’t simply a story about esports but also about larger changes in game culture and sharing your play. While the competitive gaming activity on Twitch is tremendous, it’s not just esports that is finding a home in live streaming. The medium has offered players of all kinds an opportunity to build audiences interested in observing, commenting, and playing alongside them. Live streaming was allowing gamers of all kinds to transform their private play into public entertainment. While sites like YouTube have long tapped into this desire with the ability to distribute game videos, live streaming upped the ante by offering broadcasters the opportunity to interact with their audiences in real time through a synchronous chat window. Audiences—and their interactions with broadcasters—were themselves becoming integrated into the show. Game live streaming has become a new form of networked broadcast.

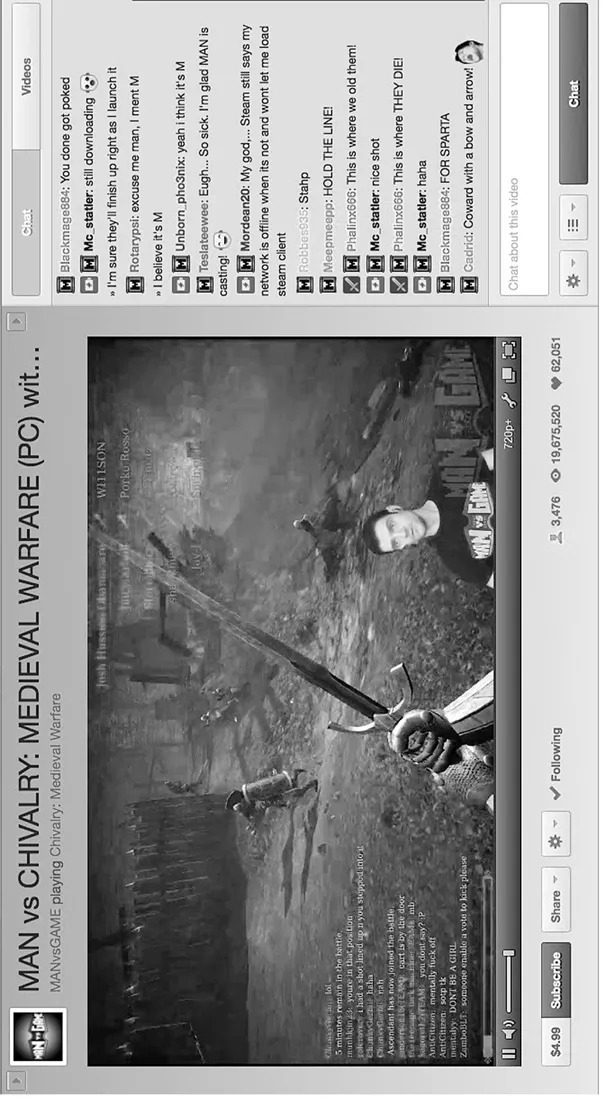

These non-esports broadcasters, typically called “variety” streamers due to the range of game titles they play (from new AAA releases to old Nintendo console games to niche indie games), are an important part of the platform. Frequently utilizing a green screen so their own face appeared overlaid onto the game, they were playing all kinds of titles in real time for a growing audience. Alongside the game and camera window, there is a chat space filled with audience members engaging with the broadcaster and each other (see figure 1.2). Rather than the kind of cheering you’d see in the chat pane during esports events, talk in these channels ranged from conversation with the streamer and others about the game or just everyday life.

FIGURE 1.2. MANvsGame broadcast, 2013.

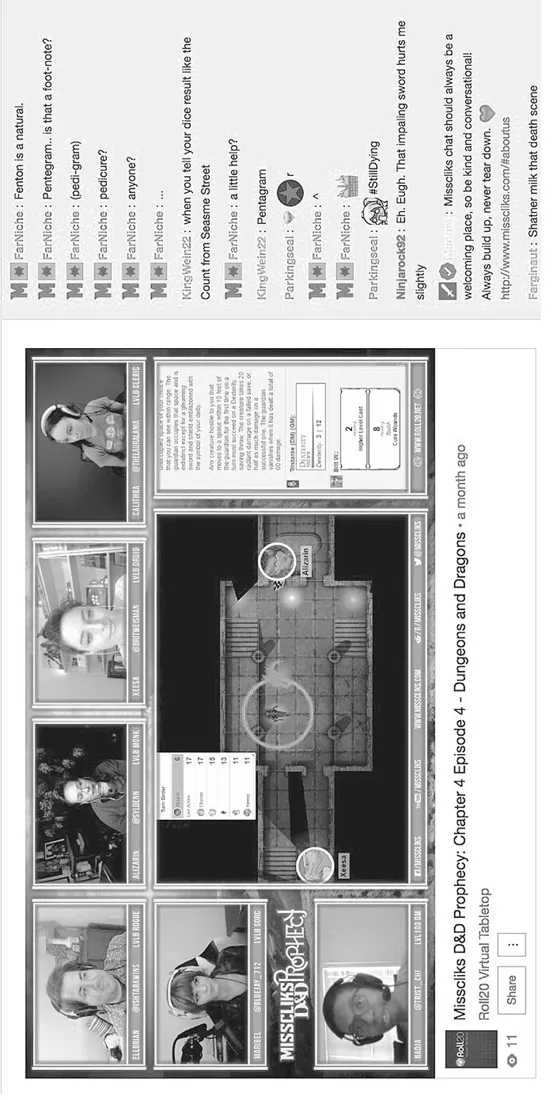

While computer games make up the lion’s share of Twitch, over just a few years, channels have also sprung up covering nondigital gaming. Avid card gamers, such as those who play Magic: The Gathering, can be found practicing and competing. Old-school “tabletop” role-playing sessions are now being streamed, complete with innovations for visualizing player characters and dice rolls (see figure 1.3).7

FIGURE 1.3. MissCliks D&D broadcast, 2017.

Alongside these diverse and sometimes-experimental forms of broadcast play, Twitch has also become a place to share creative work (such as making cosplay costumes or art), cooking and “social eating” (where people simply broadcast eating a meal), and music (from practice sessions to full-scale concerts). And in a twist back to its Justin.tv roots, the platform introduced an “in real life” (IRL) broadcast category allowing people to stream their everyday lives.

What began as a platform to support digital gaming has quickly expanded to accommodate people who want to produce a range of creative content for others. Some of these broadcasts have small audiences of friends and family who watch, and others draw thousands or even millions over the course of a weekend event. Across the platform, participants are creating new entertainment products that mix together gameplay, humor, commentary, and real-time interaction with fans and audiences. As with esports broadcasters, some variety streamers are working hard to convert their playtime to a professional job through advertising, sponsorships, donations, and other forms of monetization.

Though deeply innovative, all this creative activity is not taking place entirely outside existing media industries. Game companies, suddenly attuned to the potential of broadcast to get their products in front of gamers and build interest in their brands, are experimenting with live streaming as a form of marketing and promotion. From hosting launch events to developer chats, a number of companies are utilizing the space as a new form of PR and support. Some developers, such as Rami Ismail of the Dutch indie studio Vlambeer, have integrated the platform into their design process. In addition to live broadcasting his development sessions of the game Nuclear Throne twice a week (including real-time conversation and feedback with the audience), early builds (distributed via Valve’s Steam platform) could be purchased through Twitch, and came with special chat emoticons and a subscription to the channel.8 Game developers, such as the Massachusetts-based studio Proletariat, focused on making a title specifically for live streaming. That game, Streamline, allowed broadcasters to play in a game with their audience members, who also voted on new conditions that would instantly appear in the game to challenge everyone (such as the ground suddenly erupting in flames, thus requiring the players to jump onto platforms).

Underneath it all, technology companies—from core platform developers to third parties that build broadcasting tools—have been working to build and sustain infrastructures for video services as well as create economic models that allow them to survive. Tough engineering and network infrastructure challenges, video compression technology, and large-scale customer management systems are all being wrangled with and developed across a global context. The tremendous emergent activity occurring via live streaming is fundamentally engaged with sociotechnical artifacts built by both professional and amateur developers.

Amid the innovation and experimentation lurk a number of critical issues. Decisions about how these platforms and technologies will function is deeply interwoven with ideas about networked play, audiences, and the future of media writ large. As is the case with many user-generated content (UGC) platforms, advertising continues to be a prime model of monetization, but one that comes with its own set of persistent challenges—from ad-blocking software to ad inventories and concerns of oversaturation. On many UGC platforms, especially those that interweave original creative material with existing intellectual property, skirmishes continue to break out over ownership and regulation. The governance and management of these spaces as subcultures within a platform, hosting dynamic communities of practice, continues to pose vexing problems. And as is the case with a variety of internet and gaming communities, the tremendous creative energy driving innovatio...