![]()

Part One

UNPACKING THE TOOLBOX

Of course, it needs the whole society, to give the symmetry we seek. The parti-colored wheel must revolve very fast to appear white.

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON, “Experience“

A BOOK on diversity can find no better place to begin than by visiting Emerson, one of the greatest thinkers on diversity. Not only did Emerson celebrate and encourage differences, he dared mock those who did not think different—“A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” In looking at a crowd of people in an auditorium, Emerson saw not a crowd but a collection of individuals. He saw each person as limited and diverse in what and how each perceived. He saw our experiences and moods as constraining our abilities to see the world in its fullness. Ideally, he hoped we would stretch those experiences and expand our horizons to arrive at individual understandings.

Life is a train of moods like a string of beads, and as we pass through them, they prove to be many-colored lenses which paint the world their own hue, and each shows only what lies in its focus. From the mountain you see the mountain. We animate what we can, and we see only what we animate. Nature and books belong to the eyes that see them. It depends on the mood of the man, whether he shall see the sunset or the fine poem. There are always sunsets, and there is always genius; but only a few hours so serene that we can relish nature or criticism.

As the excerpt from the essay “Experience” makes clear, Emerson believes that how we experience the world influences how we perceive it. That is certainly true. But what are the implications of those differences? To answer that question, we need first to make better sense of what those differences are. In what follows, we too see mountains; we call them rugged landscapes. These represent difficult problems. And to quote Emerson yet again, “The difference between landscape and landscape is small, but there is a great difference in the beholders.” Those beholders who see landscapes sublimely we call geniuses. We can quibble about what it means to be a genius, and even about the extent of Emerson’s contributions, but we cannot deny his ability to see clearly what for so many others was muddled and confused. And so, it’s appropriate that we begin at his front porch. And as we take leave, we remind ourselves to follow his sage advice, to slow down the wheel.

We slow down the wheel for a specific purpose: to understand the potential benefits of diversity. Our goal is to understand when and how diversity is beneficial. We want to move beyond metaphor and reach a deep understanding. Eventually, we do that. I’ll state formal results that show that when solving a problem, diversity can trump ability and that when making a prediction, diversity matters just as much as ability. In order to make those formal claims, I need to lay a foundation.

As an analogy, consider the mathematical theorem that the area of a rectangle equals the base times the height. That result makes sense only if we know that we mean by base and by height. We have to define those terms. The same holds here. To show that diversity is beneficial, we need to define terms and concepts, so we do. I define perspectives (ways of representing the world), heuristics (techniques and tools for making improvements), interpretations (ways of creating categories), and predictive models (inferences about correlation and cause and effect).

These formal ways of capturing diversity we then lump together and call them a person’s toolbox. That’s how we think of people’s capabilities—as their collections of tools. We then use this toolbox framework to explore if, why, how, and when toolbox diversity produces benefits. We have to wait to do that, though. First, we must learn about the tools themselves.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Diverse Perspectives

HOW WE SEE THINGS

Those French, they have a different word for everything.

—STEVE MARTIN

WE all differ in how we see and interpret things. Whether considering a politician’s proposal for changes in welfare policy, a new front-loading washing machine, or an antique ceramic bowl, each of us uses a different representation. Each of us sees the thing, whatever it is, in our own way. We commonly refer to the ways we encode things as perspectives. But if asked what a perspective is, most of us would have only a crude idea. In this chapter I provide a formal definition, but before I get to that I’ll present an example of a famous perspective: the periodic table.

In the periodic table each element has a unique number. These numbers help us to organize the elements. They give structure. Compare this perspective to the perspective that uses common names such as oxygen, carbon, and copper. By convention we know what those names mean—copper is a soft brownish metal that conducts electricity—but the names don’t create any meaningful structure. They are just names. We could just as well give copper the name Kamisha.

Mendeleyev’s periodic table gave us a meaningful structure. Coming up with that perspective took hard work. To discover the structure of the elements, Mendeleyev created cards of the sixty-three known elements. Each card contained information about an element including its chemical and physical properties. Mendeleyev then spent hours studying and arranging these cards, transforming the problem into a representational puzzle. Eventually, Mendeleyev pinned the cards to the wall in seven columns, ordering the cards from lightest to heaviest. (Imagine playing solitaire on the wall using thumbtacks.) When he did this, he saw a structure that was completely understood only three decades later with the introduction of atomic numbers. Before Mendeleyev, atomic weight had been considered irrelevant. A scientist could order the elements by atomic weight from lightest to heaviest, but he could also arrange them alphabetically or by the number of letters in their name. Why bother?

As some of the elements had not been found, Mendeleyev’s table had gaps. New elements were soon found that filled those gaps. Mendeleyev took information, turned it into the pieces of a puzzle, and showed us that pieces were missing.1 Mendeleyev’s representational puzzle, unlike the problem of finding the chemical composition of salt, lacks a physical analog. He was not searching for an existing structure; he was creating a structure out of thin air. That structure revealed order in the stuff of which we’re made. His story is not unique. We can find stories like Mendeleyev’s throughout the history of science—think of Copernicus and the heliocentric universe, or of Einstein and the construction of relativity theory. In both cases, someone saw the world differently—Einstein linked space and time—and what had been obscure, confusing, or unseen became clear.

Scholars from a variety of disciplines have studied how people and groups make breakthroughs. The common answer: diverse perspectives. As the philosopher of science Steven Toulmin wrote, “The heart of all major discoveries in the physical sciences is the discovery of novel methods of representation.”2 New perspectives, what Toulmin calls “novel methods of representation,” are often metaphorical. The canonical model for earthquakes, for instance, involves blocks connected by springs, which can then be analyzed rigorously using mathematics.3 Though we know perspectives lead to breakthroughs, their sources remain shrouded in mystery. The only necessary ingredient appears to be hard work and a willingness to look at things that others ignore. That’s also a recurrent theme. Being diverse in a relevant way often proves hard. Being diverse and irrelevant is easy.

We can now define perspectives formally. They are representations that encode objects, events, or situations so that each gets its own unique name. No two chairs, no two people are represented in the same way. Mathematicians call these “one-to-one” mappings or bijections. That’s a strong but necessary assumption. The names that perspectives assign to objects capture underlying structure. If they do not, then the perspectives are not of much use.

In this chapter, we drive home one main insight: the right perspective can make a problem easy. We see how most scientific breakthroughs and business innovations involve a person seeing a problem or situation differently. The germ theory of disease transformed what seemed like an intractable confusing mess of data into a coherent collection of facts. Thanks to Adam Smith, we all know the story of the pin factory and how efficient it is. But do many of us know that the first pin factory manufactured brushes with firm steel bristles? The firm began producing pins only when someone realized that the bristles could be cut off and made into pins. Diverse perspectives—seeing the world differently, seeing the brush as a forest of pins—provided the seeds of innovation.4Let’s begin.

PUTTING OUR DIFFERENT SHOULDERS TO THE WHEEL

I first provided some hints of how diverse worldviews can be useful in solving a problem such as cracking the Enigma code. We now consider a problem related to cracking a code of a different form. This example will be a bit of a teaser for the second part of the book, when we consider the application of diversity to problem solving, prediction, and choice.

Figure 1.1 The Geometrician’s Perspective

Figure 1.2 The Economist’s Perspective

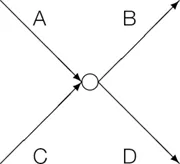

We start with a puzzling fact: in every object examined by a team of scientists, they find that the amount of A equals the amount of B and the amount of C equals the amount of D. For the moment, don’t worry about what A, B, C, and D are. What might we do with such a fact? How might we make sense of it? Let’s put on several different types of academic hats and see what we might do with it.

We might first think like geometricians and imagine that the letters represent the sides of a rectangle (see Figure 1.1). If we label the top and the bottom of the rectangle A and B, and label the two sides C and D, we can then exploit the property that the opposite sides of a rectangle must be equal. We have explained our fact. Of course, we don’t have any idea what to do with this rectangle, but still, we have an idea that whatever we find might well be rectangular.

Or we might suppose that we are economists (see Figure 1.2). If so, we might reason that A is the amount of some good supplied and B is the amount demanded. Or we might reason that A is the price of the good and B is the marginal cost. Or we might think that A is the price of an input and B is its marginal product. In each of these examples, some force equilibrates the amounts.

Figure 1.3 The Chemist’s Perspective

Figure 1.4 The Physicist’s Perspective

Figure 1.5 The Fashion Designer’s Perspective

Or we might imagine ourselves chemists (see Figure 1.3). We might reason that some chemical reaction results in molecules containing equal amounts of A and B, and of C and D.

Or we might imagine ourselves physicists (see Figure 1.4). We might then reason that A, B, C, and D are properties that must be conserved such as energy or matter that can be neither lost nor gained.

Finally, we might imagine ourselves fashion designers with nifty, small glasses (see Figure 1.5). If so, we might think of A as the number of people wearing argyle sweaters and B as the number of people wearing blue jeans. We might think of C as the number of people wearing cutoffs and D as the number wearing dingy T-shirts. If everyone wearing an argyle sweater wears jeans and everyone wearing a dingy T-shirt wears cutoffs, then A = B and C = D.

Each of these possible perspectives embeds an intelligence based on training and experience. And each of these ways of looking at the problem would prove useful in some cases and not so useful in others.

To see diverse perspectives at work, let’s look at the real story: the discovery of the structure of DNA. Francis Crick and James Watson’s piecing together of the double helix structure involved many hours of hard work and lots of dead ends. Overcoming these dead ends (what we will later call “local optima”: perspectives that look pretty good until you search further) required that they develop new perspectives on their problem. One fact at their disposal, a fact ignored by many others working on the problem, was Chargaff’s rules, which stated that a cell’s nucleus contained equal amounts of adeni...