![]()

1 The War at Home

We could see ourselves that the war made demands

not only on the nerves of the soldiers but also on those

who had to stay at home.

—Alois Alzheimer, Der Krieg und die Nerven, 1915

August 2. Germany declared war on Russia.

In the afternoon, swimming lessons.

—Franz Kafka, Diaries, 1910–1923

“Can’t films be therapeutic?”

—Ari Folman, Waltz with Bashir, 2008

The Wounded Soldier

There is no such thing as shell shock.

—George C. Scott in Patton, 1970

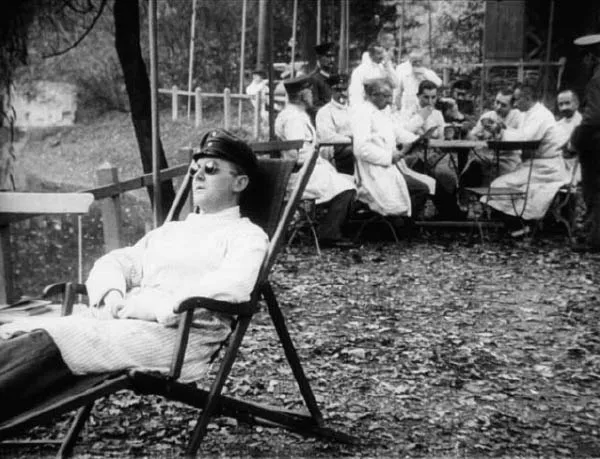

The movie, grainy and silent, begins in the middle. “Groundwater!” flashes on the screen in an intertitle, followed by a view of a young soldier trapped in a collapsed trench. He is buried under a jumble of planks and beams, and gushing water threatens to drown him. A close-up captures his distorted face from above. Like an animal pinned against the wall, he squirms to free himself, his arms flailing. Terrified by the rising groundwater, he screams for help. The camera stares at him, motionless, as if trapped itself. Cut to two soldiers who hack and saw their way through the chaotic wooden structure, struggling, along with a rescue dog, to reach the victim. In a take that seems interminable, the camera’s tight frame holds the soldier down, unflinchingly recording his imminent death. Then a sudden cut. Well-dressed men and women enter a sanitarium garden; the camera focuses on a patient, the young soldier, now wearing dark glasses that suggest blindness. We must assume he was rescued at the last minute, but his near-death experience caused a psychic breakdown resulting in the loss of sight—a frequent and unmistakable symptom of shell shock.

According to the film’s censorship cards, the soldier was found and saved by the very dog that Ossi, the soldier’s fiancée, had given up for military emergency service. The original film apparently had included an exhaustive documentary sequence depicting the ways in which civilian dogs were trained by the Red Cross for service at the front. The dog, named Senta, sits next to her blind master as he dictates to a nurse a letter to his fiancée. Cut to Ossi, played by Ossi Oswalda, a young and attractive star (known as the “German Mary Pickford”), on the home front. Idly lounging on a couch, she seems excited about the arrival of news from the front, which a servant delivers on a platter. The soldier’s letter, seen in an intertitle, reads: “Senta has saved my life and almost gave hers. Hopefully I will see you again?” The last sentence, referring to her fiancé’s blindness, is deeply ironic. She immediately asks her father if she may “see” him again, and both visit him in the sanitarium. His Seeing Eye dog recognizes Ossi and pulls her along to meet her blind lover. As they embrace, Ossi touches the soldier’s eyes, which he tries to cover with his arm. He: “I don’t know if I will ever see again, and you want to stay with me?” She, emphatically nodding: “I will guide you—toward the light.” His black glasses glint in the sun; he appears soothed and happy. Cut to a domestic setting, followed by a title: “And a morning of a new vision came.” He takes off his glasses, miraculously cured. As the couple opens the window shades, light falls into the room. A final title reads: “With new eyes toward new light.” A last image is devoted to a close-up of Senta, the dog who saved our hero’s life. The end.

This remarkable ten-minute fragment is all that remains of Georg Jacoby’s film Dem Licht entgegen (Toward the Light). It is the only extant film from World War I that dares to show both the cause and effects of shell shock as a psychosomatic illness. One of the first feature films made for the newly established Universum-Film-Aktiengesellschaft, or Ufa, Toward the Light was shot in December 1917.1 It opened on April 1, 1918, at a time when casualties from the last battles of the war were mounting, and the home front had to cope with thousands of soldiers returning home physically wounded or mentally broken. Because World War I was by and large fought outside of Germany, wounded soldiers became the most visible reminders of the war’s devastation. Toward the Light’s spatial trajectory—from the trenches to the sanitarium to the living room—illustrated the gradual intrusion of the battlefield into the home front. It also made plain the reward for sacrifice on the home front: by giving up her dog to the war effort, Ossi saved her fiancé’s life. Further, because she agreed not to abandon the blinded soldier, she is rewarded with his recovery. The message for the home front was clear: military and civilian lives are inextricably intertwined. If you give to the war effort, you will be amply compensated. Sacrifice pays.

What astonishes in this film is the stylistic contrast between the harsh realism of the trenches and the overdecorated domestic space. As if shot by a different cameraman, the drawn-out agony of the young soldier, trapped and drowning in a collapsed trench, addressed fans of action and adventure pictures. Such films typically showed the hero struggling against the elements and being saved at the last minute. Toward the Light maps this genre pattern onto a war scenario, giving the audience a fictional glimpse of what the battlefront was like. The film does not show combat scenes nor does it glorify war; instead it focuses on a war-related, psychosomatic injury and its impact on the home front.

A propaganda film at heart, Toward the Light seeks to demonstrate that a woman’s selfless loyalty heals the wounds of the broken soldier. The film is specifically directed at women on the home front, who in early 1918 had to face the likely prospect of having husbands and fiancés return from the war crippled or shell-shocked. Men lucky enough to come back at all were often physically or psychologically damaged, powerless, and dependent on the help of others. They returned to wives who had become strong and assertive during their long absence, and who had in many cases been unfaithful. The protagonist’s question, “Will you stay with me?” articulates this anxiety. The scene in our film fragment also encapsulates a new power dynamic: while the young man is shell-shocked and childlike, his bride is steadfast and nurturing, assuming the additional roles of mother and nurse.

Coming down to us as a mere remnant of a full-length feature film, like a piece of shrapnel that has accidentally survived, Toward the Light is a revealing document. Not only does the film’s broken, fragmentary state uncannily reinforce its abrupt stylistic breaks and sudden reversals of fortune; it also dramatically demonstrates the brazen way in which Ufa resignified the life-threatening danger of the battlefield within a propagandistic framework. The film manages to provide a positive, even erotic spin on the crippling illness of shell shock by holding out the hope that with time and affection, even this most mysterious and horrifying psychological wound can be healed.

Although symptoms of shell shock—loss of vision, hearing, and speech; amnesia; paralysis; and sudden violent outbursts—had been reported in earlier wars, the term itself was not coined until about six months into the First World War. In February 1915, an article titled “Contribution to the Study of Shell Shock” appeared in The Lancet, the leading British medical journal, in which the military doctor Charles S. Myers described the blindness and memory loss that three frontline soldiers experienced after heavy shelling.2 Because no physical injury could be found, Myers speculated that the shock caused by bursting shells and exploding grenades brought about yet undetected physical changes (for instance, microscopic lesions) in the brain and spinal cord. Shell shock was understood here as a somatic condition, or basically a wartime variation of what in 1899 the German neurologist Hermann Oppenheim had termed “traumatic neurosis.”3

According to Oppenheim, traumatic neurosis could be triggered by a sudden physical shock to the central nervous system. Events such as railway collisions, industrial catastrophes, or traffic accidents often set off hysterical or neurasthenic symptoms even in those who had survived the impact otherwise unharmed. Oppenheim himself stood within the nineteenth-century tradition of psychiatry that decreed all mental or nervous diseases to be the result of physical damage to the brain. This somatic theory had come under attack during the 1880s and 1890s, however. Younger neurologists—among them Hippolyte-Marie Bernheim, Pierre Janet, and Sigmund Freud—argued that mental and nervous diseases, including hysteria, neurasthenia, and traumatic neurosis, were not necessarily brain diseases but rather disorders of the mind, best treated by mental means—that is, psychotherapy, hypnotism, and psychoanalysis. Hysterical and neurasthenic cases had a wide range of symptoms, including catatonic stupor, shaking, paralysis, blindness, depression, and hallucinations, but no somatic basis for them could be found. The symptoms were present even though no bodily shock to the spinal cord, the peripheral nerves, or the brain itself had occurred. Questions arose: Can there be psychological damage without physical cause? Can bodily symptoms be generated and “willed” by the mind? Was it possible to simulate mental disorder if some advantage could be gained from it?

Shell shock victim after he is rescued from a collapsed trench. The trajectory of war—from the trench to the sanatorium—in Georg Jacoby’s Toward the Light.

There were two competing schools in psychiatry at the time of the First World War: one claimed that traumatic neurosis had a physical origin (even though no bodily wounds could yet be detected); the other contended that it was “all in the mind,” and thus had more to do with unconscious desire, mass suggestion, and the will to deceive than with physical injury. The debates about traumatic neurosis at the turn of the century gained new urgency in late 1914, after the first major battles had produced an astonishingly high number of mental breakdowns. Soldiers and officers had to be removed from the front and sent to mental institutions for treatment of shell shock. Alois Alzheimer, a professor of neurology and a specialist in memory loss at the University of Breslau, addressed the impact of war on the nervous system in a public lecture in 1915:

So we see, for example, that soldiers in war lose their speech or hearing or become suddenly deaf-mute simply by being in the vicinity of an exploding grenade. Without being hit by shrapnel or injured in any way, they show signs of paralysis in their legs or in a part of their body, or they experience cramps, totally as a result of the violent shock. In other cases, a so-called cataleptic state develops, a numbed, dream-like state of consciousness, in which the patient appears disoriented about place and time, making all sorts of confused remarks, often tied to the shock experience.4

Alzheimer identified other symptoms of this “shock experience,” such as somnambulism, sudden unconsciousness, convulsion, tics, and tremors. What he described were typical symptoms of shell shock victims or, as they were called in German, Kriegszitterer (war quiverers). The traumatic neurosis of the nineteenth century, associated with railway crashes and industrial accidents, had reemerged on a massive scale as war neurosis.5

Traumatic neurosis was the conceptual model used at the beginning of the war when dealing with soldiers suffering mental breakdown. Kriegsneurose, or war neurosis, suggests a stronger psychological dimension than is implied in the term shell shock, which emphasizes somatic impact.6 Shell shock covered a large terrain of psychological and physical illnesses that baffled not only the military but the medical establishment as well. Even the healthiest soldiers on the battlefield could be suddenly stricken by a severe mental breakdown, suffering bodily symptoms that ranged from catatonic stupor to blindness, from shaking to rigor mortis. The number of soldiers turning paranoid, hysterical, and crying uncontrollably was unprecedented. What kind of illness was this?

On the most basic level, shell shock was an unconscious rebellion and bodily reaction to the horror of trench warfare, which on the western front settled into a stalemate as early as the fall of 1914. Weeks of endless waiting in the trenches alternated with suicidal attacks across no-man’s-land into the enemy’s trench, where soldiers often charged right into the teeth of machine-gun fire. Commanders dispatched entire divisions of men only to see them mowed down in serried rows. The mind-searing mass slaughter of long-range artillery fired by unseen opponents, the bombardment, and the resulting wounds caused long-term “combat fatigue” even among those not suffering from shell shock.

The German military justifiably feared an epidemic of soldiers simulating shell shock symptoms in order to escape the front. It enlisted psychiatrists, who had pledged before all else “to serve our military and our fatherland,” to help identify malingerers among war neurotics and return them to the front as quickly as possible.7 At a 1916 war conference in Munich, the psychiatric establishment decided to reject Oppenheim’s view that traumatic (and now war) neurosis must have a physical cause, even if it was undetected and invisible.8 Instead, it followed Oppenheim’s opponents—Robert Gaupp, Max Nonne, Ferdinand Kehrer, and Fritz Kaufmann—who strenuously argued that war neurosis was imagined and willfully induced by morally inferior minds bent on evading military service. These psychiatrists pleaded for the harsh punishment of war neurotics as suspected malingerers. While some doctors treated shell shock by experimenting with hypnosis, strict isolation, and extended hot baths, Kaufmann promoted the use of electroshock (the so-called Kaufmann Cure), applying painful electric currents to scare patients “into health” so that they could return to the front as cured. When diagnosed as deliberate defiance of military duty, war neurosis was suddenly no longer only a medical category; it became a social and political tool, used to repress and regulate behavior that doctors in the service of the military saw as “deviant.” For the majority of the psychiatric establishment, the breakdown of a young soldier was considered ample proof of a psychopathological disposition. It is not surprising that war psychiatrists were among the most despised professional classes after the war, and it was clearly provocative to portray the psychiatrist in Robert Wiene’s 1920 film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari as a villain who masterminds a string of murders.

Men suffering from shell shock found themselves isolated and estranged from their families at home. Their psychosomatic illness made it hard to resume their place in society. It was up to a propaganda film like Toward the Light to suggest ways of reintegrating shell-shocked soldiers into domestic life. Women were called upon to support all men who had been psychologically damaged and physically brutalized b...