![]()

1

WHAT INVESTIGATORS HAVE DISCOVERED

Although empirical research on happiness hardly existed be a fore 1970, it has since become a boom industry. Mounds of evidence have accumulated on how happy people claim to be in different countries, how their levels of contentment vary from one subgroup of the population to another, and what conditions or experiences are most closely related to the way people feel about their lives.* Several thousand articles have now been published on the subject. Books on how to be happy fill entire shelves in Borders and Barnes & Noble. International conferences abound. There is even a scholarly journal devoted exclusively to the topic.

Happiness is a large word encompassing many shadings of feeling and emotion. No single definition can do full justice to all that it embraces. The dean of American happiness scholars, Ed Diener of the University of Illinois, does his best to respond by offering the following comprehensive definition: “a person is said to have high [well-being or happiness] if she or he experiences life satisfaction and frequent joy, and only infrequently experiences unpleasant emotions such as sadness or anger. Contrariwise, a person is said to have low [well-being or happiness] if she or he is dissatisfied with life, experiences little joy and affection, and frequently feels unpleasant emotions such as anger or anxiety.”2

Most of the empirical research to date is based on surveys that ask individuals how happy or how satisfied they are with their lives. But that is not the only method used. As we will discover shortly, investigators can also ask people how they felt at various specific times during the day—at work, playing with children, cleaning up the yard, or socializing with friends. Although the latter technique yields valuable results, the former method is far more commonly used and therefore accounts for the findings discussed hereafter except where otherwise indicated.

The Relation of Income to Happiness

Investigators have examined a long list of factors in an effort to determine their effect on well-being. Among them, income has been studied most intensively, possibly because so many people believe that a bit more money would be the change in their lives most likely to bring them greater happiness. As it happens, however, the effects of money turn out to be a great deal more complicated.

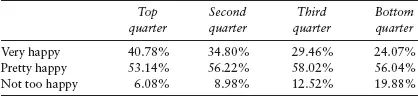

One finding is clear. At any moment in time, average levels of happiness in the United States are higher as one moves up the income scale. (See table 1.)

Similarly, global surveys show that differences in average happiness among nations are highly correlated with differences in their average per capita incomes.3 With only a few exceptions, wealthier countries have happier populations than poorer nations.

TABLE 1

Levels of Satisfaction by Income Quartiles (1975 to 1992)

The figures above are taken from Rafael Di Tella, Robert J. MacCulloch, and Andrew J. Oswald, “The Macroeconomics of Happiness,” 85 Review of Economics and Statistics (2003), p. 809, table 1.

These findings seem to reflect what economists have long assumed: that income plays a major role in people's happiness. Surprisingly, however, longitudinal studies that trace the happiness of a sample of people in prosperous nations over long periods of time show that most people's satisfaction with life tends to change very little with the rise and fall of their income as they progress through their careers and eventually retire.4 More puzzling still, as pointed out in the introduction, a number of studies have found that average levels of satisfaction with life have not risen appreciably in the United States over the past 50 years, even though real per capita incomes have grown a great deal during this period.5

Much controversy has arisen over how to reconcile these findings. Why haven't rising levels of prosperity raised the reported levels of happiness if people with higher incomes tend to be happier than those with less money? Analysts have advanced several theories to explain the seeming paradox.

One explanation could be that richer people are happier, not because higher incomes make them so but because happier workers are more successful and earn more money. There is something to this argument. One study, for example, found that students who were identified as happier when they entered college earned 30 percent more by the time they were 40 years old than classmates who were rated less satisfied as freshmen.6 It is doubtful, however, that this explanation can account for more than part of the gap in well-being between rich and poor Americans.

Another possibility is that income growth has indeed brought greater happiness but the effects have been nullified by other trends in the society that have depressed well-being, such as increased levels of divorce, crime, drug use, unemployment, and the like. On first glance, this theory seems promising. As it happens, however, scholars who have tried to account for all the known trends that might affect happiness other than economic growth have concluded that the positive trends are potent enough that the net effect should have been to increase happiness even more instead of holding it back.7

Other analysts have pointed out that the economic growth experienced in the United States since 1975 has largely gone to the wealthiest 20 percent of the population. Since only this small minority have benefited, it is arguably not surprising that the average happiness of the population as a whole has failed to rise.8 This explanation too seems initially plausible. One problem with it, though, is that the distribution of happiness between rich and poor has not grown more unequal in the past 30 years, suggesting that even the fortunate fifth who have seen their incomes rise have not become happier as a result.9 Another awkward fact is that levels of happiness in the United States appear to have stagnated, not merely since the 1970s but over a considerably longer period.10 In fact, well-being reportedly declined slightly from the mid-1950s through the 1960s, even though incomes were growing smartly during this period for all segments of the population. Finally, this theory does not explain why happiness has failed to rise during the last 20 years in several other well-to-do countries, such as Belgium, Switzerland, Norway, and Austria, where the fruits of growing prosperity have been more evenly distributed throughout the population than in the United States.

A fourth possible explanation is that satisfaction with one's financial situation depends in large part on how one's income compares with the incomes of others.11 Thus, some investigators have found that the effects on happiness of a change in income are influenced significantly by what is happening to the incomes of one's friends, co-workers, and neighbors, especially those with whom one socializes.12 As a result, any satisfaction people gain from a boost in their income tends to be eroded significantly if incomes all around them are rising just as fast. It follows that when prosperity is increasing throughout the nation as a whole, the average level of happiness will not rise correspondingly.

The positive effects of rising standards of living can also dissipate as people get used to higher incomes and begin to aspire to even greater riches.13 For example, in 1975, at a time of stagnating incomes, 74 percent of Americans said that “our family income is high enough to satisfy our most important needs.” By 1999, although per capita incomes had risen substantially, only 61 percent made the same claim.14 Similarly, although the median estimate of the income Americans felt they needed to “fulfill all of [their] dreams” was approximately $50,000 in 1987, the necessary amount rose to $90,000 (in constant dollars) by 1996.15 Observing these trends, analysts have described the pursuit of financial goals as a treadmill in which people's aspirations are forever beyond their reach, leaving them perpetually unsatisfied.

Rising aspirations and adaptation to higher living standards may account for the failure of happiness to rise in America over the past 50 years, but they do not explain how richer people came to have higher average levels of happiness than poorer people in the first place. Some light may be thrown on this question by yet another theory. Perhaps the added happiness of wealthier groups in the society does not come about primarily from money per se or from the goods that money can buy but from the subtler rewards that tend to accompany greater wealth. One such benefit might be the satisfaction that comes from feeling more successful or having a higher status than people of lesser means. A second benefit could be the greater challenge, independence, and intrinsic interest associated with the kinds of jobs that persons with higher incomes tend to hold. Since the hierarchies that account for these added satisfactions have always existed and will presumably persist regardless of how much or how little a nation's standard of living rises, one should not be surprised if the overall level and distribution of happiness are unaffected by growth. Whether per capita national incomes increase, stagnate, or decline, there will always be people at the top enjoying more interesting jobs, recognition, and freedom of action as well as people lower down the ladder whose work is more routine and who must endure the petty frustrations and disappointments of being less valued and more subordinate than those at higher levels in the social and economic hierarchy.

Until recently, scholars debated the merits of the various theories just described. Many of them accepted the conclusion that economic growth increased well-being substantially only in relatively poor nations where most people had too little to meet even their basic needs. According to this theory, once a country achieved a per capita income of $10,000–$15,000 per year, further growth yielded little if any increase in happiness. In 2007, however, Angus Deaton analyzed the results of the recent Gallup World Survey and concluded that if one compared percentage increases in per capita income, rather than absolute dollar increases, and if one disregarded the former Soviet bloc countries, which had gone through exceptional change and turbulence after the collapse of Communism, a given percentage increase in Gross National Product brought at least as great a boost in well-being in prosperous countries as it did in poorer nations.16 A subsequent analysis by Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers reached the same conclusion.17 If this finding holds, the seeming paradox disappears and no longer needs to be explained.

Deaton's conclusion, however, is by no means generally accepted, at least not yet. Much previous research contradicts it, and even experts who agree that economic growth brings greater happiness in prosperous countries often find that the rate of increase is very slight. The European happiness scholar Ruut Veenhoven, for example, claims that if happiness in the United States continued to rise at the rate of the past 40 years, it would take 167 years to gain a single point on a ten-point scale of well-being.18 Other analysts who have studied the recent Gallup data, including Stevenson and Wolfers, still concede that well-being has risen very little in the United States over the past half century.19 Thus, although the Gallup results have provoked a lively debate, they have not yet produced a consensus that explains the underlying puzzle.

What does this controversy mean for the countless individuals who set great store by achieving financial success? Annual surveys of college freshmen across America over the past 35 years have consistently found that over 70 percent of these students feel that making a lot of money is a “very important goal.”20 Could they be making a serious mistake and might they ultimately find that financial success brings no added happiness in its wake?

Certainly, those who climb to the highest levels of the financial ladder tend to be significantly happier than those who remain on the lower rungs. Regardless of how little they come to relish their opulent lifestyles and however fleeting their enjoyment of vacation homes, expensive cars, and other luxuries that poor people cannot afford, they can at least savor the subtler satisfactions of worldly success. Their jobs tend to be more interesting, they have more control over how they spend their time, and they are more likely to give orders than to receive them. The mere fact that they have succeeded in what they set out to achieve should make them more satisfied with their lives. These considerations might seem to justify placing a high priority on financial success.

Yet psychologists report that those who attach great importance to achieving wealth tend to suffer above-average unhappiness and disappointment.21 One can think of several reasons why. Presumably, many of those who are preoccupied with becoming rich will fail to realize their ambitions and feel acutely disappointed as a result. Even those who succeed may become so preoccupied with money that they neglect the human relationships that affect their happiness. In fact, researchers have found that the more people care about becoming rich, the less satisfaction they tend to derive from their family life.22 Finally, those who do achieve some financial success are likely to find much of their added happiness short-lived. As previously explained, people grow used to the extra possessions that higher incomes allow; luxuries turn into necessities and aspirations rise, leaving them no more satisfied with life than before.

How to reconcile these conflicting observations is not entirely clear. Probably, the happiest people among the well-to-do tend to be those who were never too preoccupied with financial success but prospered by working hard at what interested them most while managing not to sacrifice family and friendships along the way. In addition, one group of researchers has discovered that many who care a lot about making money and do succeed in becoming rich gain a satisfaction from their accomplishment that offsets any loss of well-being they experience from sacrifices made in other aspects of their lives.23 Even so, however, not all who aspire to great wealth will succeed. At the very least, therefore, the findings of psychologists convey a warning that being preoccupied with getting rich carries a substantial risk of leaving one unhappy and disappointed in the end.

If the search for wealth yields such uncertain rewards, why do so many people try so hard to achieve it? One can only guess at the answer. Perhaps the concern with money and possessions took root in much earlier times when most people were poor enough that added income was essential to overcome genuine privation and want. Perhaps material desires continue to be nurtured and reinforced by constant advertising and vivid media portrayals of the possessions and lifestyles of wealthy people. It is also possible that in an ambiguous world where genuine success is often hard to define, people seize on income, salary, possessions, profits, sales, and market shares as tangible measures of what they have achieved in life and what they might strive to accomplish in the future. Many Americans might even find it difficult to muster much ambition or see much meaning in their lives if they did not have money and the things that it can buy to spur them on.

Other Sources of Happiness

Financial success is not the only prominent aspect of life that seems to contribute less to happiness than most people suppose. Demographic differences also have relatively little impact, at least in the United States. Age does not count for a great deal.24 For most people, apparently, well-being declines slightly from their youth until they are about 40 and then improves very gradually until they reach their early 70s (assuming one controls for variations in health).25 As for gender, white women wer...