![]()

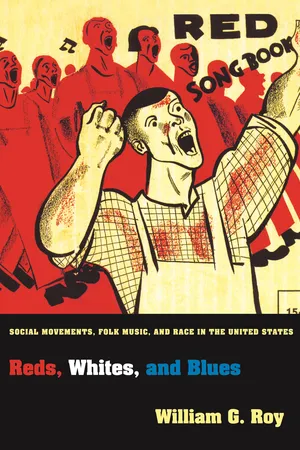

CHAPTER ONE

Social Movements, Music, and Race

On December 23, 1938, the left-wing magazine New Masses sponsored a concert in New York’s Carnegie Hall titled “From Spirituals to Swing,” featuring some of America’s now-legendary African American performers, including Count Basie, Sister Rosetta Tharp, Sonny Terry, and the Golden Gate Quartet. The program notes put the music in social context: “It expresses America so clearly that its readiest recognition here has come from the masses, particularly youth. While the intelligentsia has been busy trying to water our scrawny cultural tree with European art and literary movements, this thing has come to maturity unnoticed” (“From Spirituals to Swing” program). One of the songs, “I’m on My Way,” could be heard a quarter century later in freedom rallies in places like Albany, Georgia. Commentators again embraced the sounds of African American culture as the music of America. Other parallels are found. The 1938 concert and 1961 Albany musicking each occurred during a peak of social movement activity, the communist-led Old Left that resulted in the unionization of America’s core industrial sector, and the civil rights movement that crippled the insidious system of legalized racial segregation. In both, African Americans and whites joined to make music, challenging the dominant racial order that infected all aspects of social life. The aspirations of both movements to bridge racial boundaries with music were explicit—wedding black music (spirituals) and black-inspired white music (swing) in one event and invoking a universal principle (freedom) in the other. And both were but one moment of many in larger cultural projects that have used music in pursuit of social change.

But the contrasts were equally important. Most important, “From Spirituals to Swing” was a performance. One group of people sang and played for another, who participated as an audience. As such it succeeded, parlaying the popularity of such stars as Benny Goodman to launch performers like the Golden Gate Quartet and inject popular music with African American sensibilities. Still, the larger leftist movement was not able to change the musical tastes of their core target constituency, the American working class. Freedom songs, on the other hand, though made familiar by media coverage of the movement, had relatively little commercial impact. They did, however, have a huge impact on the movement, affording racially diverse activists the opportunity to join together in a somatic experience of unity. This distinction is the theme of this book: the social form of music—specifically the relationship between those who sing and those who listen—reflects and shapes the social relationship between social movement leaders and participants, conditioning the effect that music can have on movement outcomes.

THE PROBLEM

I demonstrate the effects of the social relationships within music on the social effects of music with a comparison of the Old Left/communist-led movement of the 1930s and 1940s with the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Both movements self-consciously adopted folk music as a cultural project, both motivated by the potential of folk music to bridge racial boundaries, but with very different effects. The Old Left succeeded in boosting folk music from an esoteric genre meaningful to academics and antiquarians into a genre of popular music familiar to ordinary Americans. But it was never embraced by their rank-and-file constituents, especially the African Americans they aspired to mobilize. The civil rights movement, in contrast, had little interest in putting freedom songs on the charts. Even those that eventually became universally known, such as “We Shall Overcome,” were never commercial hits. But participating in the movement meant doing music. The impact of “We Shall Overcome” and other freedom songs was less important for their mass appeal than in the activity of blacks and whites joining arms and singing together. Thus the thesis of the book is that the effect of music on social movement activities and outcomes depends less on the meaning of the lyrics or the sonic qualities of the performance than on the social relationships within which it is embedded. This implies that music is fundamentally social. Accounts and perspectives that focus solely on textual meaning or sonic qualities disregard a profound sociological dimension of how music operates in social interaction. Music is a social relationship, and glossing over the interaction of people around music clouds over the explanatory power that sociological analysis can bring.

FOLK MUSIC IN AMERICAN CULTURE

Folk music has played a special role in twentieth-century politics and culture. In contrast to Europe, where folk music is characteristically associated with nationalist sentiment, American folk music carries a distinctively leftist tinge. If any American style is associated with the left as a genre, not just songs with radical lyrics, it is folk music. Alan Lomax, perhaps the most influential definer of what American folk music is, explained folk music’s appeal: “first, in our longing for artistic forms that reflect our democratic and equalitarian political beliefs; and second, in our hankering after art that mirrors the unique life of this western continent—the life of the frontier, the great West, the big city. We are looking for a people’s culture, a culture of the common man” (2003a: 86). These themes—the political, the nostalgic, and the populist—have been intertwined, weaving a consistent symbolic thread through the music’s history. The combination is powerful. Many Old Leftists remember Woody Guthrie and Paul Robeson more vividly and fondly than any Communist Party official. Ask any graying veteran of the civil rights movement to recall the era and it is often the recollection of “We Shall Overcome” that makes him or her choke up.

The political meaning of folk music is based on its “ownership” by the left. The Old Left activists in the 1930s and 1940s and the civil rights activists of the 1960s claimed folk music as their own. As we shall see, American folk music had originally more of a nationalist, even racial connotation. The nostalgic meanings of folk music initially had more affinity with a conservative critique of modernism, affirming simple, rural life in the face of industrialization and urbanization. But the Old Left redefined the genre, tapping its populist overtones as “the people’s music” on behalf of radicalism. This was music (supposedly) unspoiled by phonographs or radios, music from people who made a living by honest toil, who retained the pioneer spirit that made America great. It was music based not on the banalities of “June, croon, and spoon” but the rugged experiences of logging, sailing, children dying, and outlaws. And it was music that came from the heart and spoke to the heart. Rather than a song written to sell records, folk music was seen as music that reflected the real-life experiences of real people, singing about things that mattered. Ballads told stories of people’s lives, work songs set the rhythm of toil, spirituals voiced sorrow and hope, and reels offered a respite from the toil.1

The meaning of folk music, its appeal, and the social relationships it reinforces or erodes are not inherent features of the genre. The concept of folk music is socially constructed, in the sense that its origins must be explained historically. It is the result of specific cultural projects—coordinated, self-conscious attempts by specific actors to create or reshape a genre. As elaborated below, the projects that shaped American folk music endowed it with a political message, appealed to a specific constituency, and set it within particular social relationships. Among the most contested issues was the definition of who constituted “the folk” of folk music. In the American context that means that race hovered over these projects, as activists struggled to include or exclude racial minorities, especially African Americans.

But before we get to the story, we need to clarify the issues at stake. The thesis that the Old Left was less successful than the civil rights movement at using folk music to bridge racial boundaries but more successful in making it a permanent part of American popular music intersects three areas of sociology: social movements, the sociology of music, and the sociology of race.

SOCIAL MOVEMENTS

A social movement can be defined as a form of contentious politics with three elements: (1) there are campaigns of collective claims against targets, usually powerful organizations like governments or corporations; (2) these campaigns draw on a widely shared repertoire of organizational forms, public meetings and demonstrations, marches, and so forth; and (3) the campaigns make public representations of their worthiness, unity, numbers, and commitment. Social movements are contentious insofar as they make claims, which if realized would adversely affect the interests of some other group (Tilly 2004b).

Sociologists began to pay serious attention to social movements after they, like just about everyone else, failed to anticipate the proliferation of social movements in the 1960s. The issue garnering the largest share of attention has been why social movements arise when and where they do and why people join them. In response to scholars who explained social movements as non-rational responses to social strain, most sociologists in the 1960s and 1970s emphasized organizational processes, the mobilization of resources, and the opportunities afforded by the political context. In the 1980s and 1990s scholars broadened the agenda to examine cultural factors (Alexander 1996; Eyerman and Jamison 1991; Jasper 1997; Johnston and Klandermans 1995; Kane 1997; Snow et al. 1986). But the agenda remained focused on why social movements arise and why people join them.

Less common until recently has been work on what social movements actually do, especially with culture, and what consequences have ensued. What social movements actually do comprises not just the activities such as demonstrations, marches, sit-ins, and strikes that presumably achieve goals but also the mundane activities of meeting, chatting, debating, and deliberating. Most of the literature on what social movements do assumes that activities are designed either to achieve the official goals of the movement, “social change” of some sort, or to recruit and retain members.2 Scholars have long examined how internal relations affect the achievement of goals.3

While social movements do mobilize organizations to recruit members and carry out collective actions, much of the time is spent hanging out and meeting. As the title of Polletta’s book on participatory democracy succinctly puts it, “freedom is an endless meeting.” Polletta shows that social movements construct their internal social relationships on implicit or analogical templates of other social relationships. American movements that intentionally organized themselves around participatory democracy evoked familiar analogies to guide their practices. For some, a social movement was like a religious fellowship in which those with conscience were invited to deliberate until a consensus was achieved. Pacifist movements often followed this mode. Other movements followed a model of tutelage or tutorial, in which leaders or organizers elicited the concerns and aspirations of political novices to empower grassroots upheaval. Finally, many movements operated as groups of friends in which trust and personal commitment solidified the arduous work of setting goals and making decisions.

People who create social movements shape the social relations within them—both with constituents and with targets—on the basis of taken-for-granted templates from their experience tempered by the kinds of goals they are pursuing. Social movements are constructed not only in the image of other social movements but in the image of other institutions. Social movements can be modeled on quasi-political parties, churches, families, schools, clubs, armies, and even firms. These templates influence the kind of leadership, hierarchy, and authority, whether the movement organization has membership, and, if so, the openness of membership and obligations of membership.

These relationships within an organization are one of the main determinants of what social movements do with culture. A movement patterned after a political party is more likely to use culture to recruit and educate a targeted constituency than one patterned after a church, in which culture plays more of an expressive function reinforcing solidarity and commitment. When culture is used for recruitment and education, the emphasis is more on the political content than the form. In contrast, a movement using culture to fortify solidarity is more likely to attend to the social relations within the cultural practices. This is the pattern found in the use of music by the Old Left in the 1930s and 1940s and the civil rights movement in the 1960s. The former used music, as they used theater, dance, poetry, fiction, and art, as a weapon of propaganda, a vehicle to carry an ideological message. Even though the people who promoted music in that musical project hoped that members and constituents would fully participate in music and developed a new form of participatory music, the hootenanny, the social relations inside the movement did not foster broad cultural participation.4 The fundamental relationship of culture remained performers and audiences. The musical activities of the Old Left were inspirational and supplied many of the songs for the civil rights movement, but they were refracted through a different set of social relations. The civil rights movement was rooted in a social institution used to doing music collectively, the church. The meetings where new members were recruited, where decisions were made, and where collective action was planned evoked religious services in both form and function. Most of the people were used to singing together when they gathered in groups. The social relationships were more like congregational singing than performers and audiences. Dr. Martin Luther King explicitly made the analogy between the movement and the church: “The invitational periods at the mass meetings, when we asked for volunteers, were much like those invitational periods that occur every Sunday morning in Negro churches, when the pastor projects the call to those present to join the church. By twenties and thirties and forties, people came forward to join our army” (1963: 59).

What does this tell us about social movements and music? First, it tells us that social movements mobilize around culture. Culture is not just something that movements have; it is something they do. What movements do with culture is just as important as the culture they have. Most of the literature on culture and social movements treats culture as a mental characteristic of the participants, asking either how the mental modes by which participants handle symbols affect their propensity to act or what meanings actions have for participants (Eyerman and Jamison 1991; Jasper 1997; Johnston and Klandermans 1995; Kane 1991; Steinberg 1999). Social movements develop identifiable organizations that bring people together, employ resources, and seek goals. Without organizations that have erected apparatuses and mobilized resources, social movements will either fail to develop culture or lose control of the culture, as happened with the New Left of the 1960s.

My concept of culture differs somewhat from the best-known book on the topic, Eyerman and Jamison’s excellent Music and Social Movements (1998). They frame their analysis around the concept of “cognitive praxis,” which they define as knowledge-producing activities that are carried out within social movements (1998: 7). This is consistent with their view that social movements are basically knowledge-bearing entities and that their main consequence is cultural change. Culture is treated as a symbolic and discursive realm existing at the social level but operationally found in individual expression. That is, culture is treated as something “out there” in the society but internalized in individuals, who provide a window on society. Insofar as culture is a system, it is a system of symbols and meanings. Analysis thus focuses on the content of that system more than the concrete social relations that embed it. Thus, cognitive praxis focuses on the relationship between the social movement and the mind of the activist.

Eyerman and Jamison open their book telling about a 1995 memorial celebration for folk music activist Ralph Rinzler at the Highlander Center (which is discussed in chapter 7): “We saw, and felt, how songs could conjure up long-lost social movements, and how music could provide an important vehicle for the diffusion of movement ideas into the broader culture” (1998: 1). This interpretation misses one of the most fundamental differences between the musical achievements of the Communist Party and those of the civil rights movement.

Diffusing cultural content or cultural forms is not the same as developing a rich cultural life within a movement. Movements vary in the extent to which they develop a distinctive cultural life in contrast to or at odds with the broader culture. Just as the literature on framing problematizes the consonance or dissonance of ideological or discursive worldviews between movements and broader audiences, analysts of culture must problematize the alignment of aesthetic content and form. A movement’s ability to contribute to and even shape culture in the larger public is analytically and often empirically different from its ability to sustain a vibrant cultural world within its own ranks. Moreover, when movements do develop their own cultural vitality they differ in the extent to which their aesthetic tastes align with those of their constituencies. In contrast to the Communist Party, which was more successful at diffusing movement culture into the broader culture, the civil rights movement was more successful at facilitating music as an integral part of collective action that actually informed movement practice.

CULTURAL PROJECTS

The work that social movements do to use culture on behalf of movement goals can be called a cultural project. For social movements, a cultural project is a self-conscious attempt to use music, art, drama, dance, poetry, or other cultural materials, to recruit new members, to enhance the solidarity of members, or to persuade outsiders to adopt the move-ment’s program.5 Often carried out by specialists in the movement, they typically deliberately decide which genres to adopt, the cultural forms that are appropriate, how culture contributes to the goals of the movement, and what makes culture political. They also to some extent develop a cultural infrastructure, producing, distributing, and promoting their cultural work. Both the Old Left in the 1930s and 1940s and the civil rights movement in the 1960s adopted American folk music as a cultural project. They not only extolled the music but built organizational infrastructures and adopt...