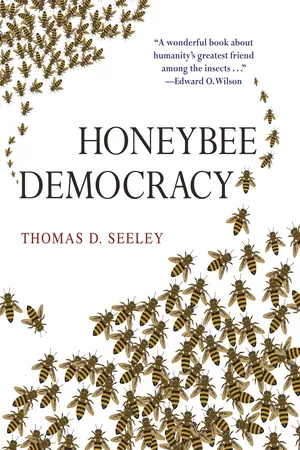

![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Go to the bee,

thou poet:

consider her ways

and be wise.

—George Bernard Shaw, Man and Superman, 1903

Honeybees are sweetness and light—producers of honey and beeswax—so it is no great wonder that humans have prized these small creatures since ancient times. Even today, when rich sweets and bright lights are commonplace, we humans continue to treasure these hard-working insects, especially the 200 billion or so that live in partnership with commercial beekeepers and perform on our behalf a critical agricultural mission: go forth and pollinate. In North America, the managed honeybees are the primary pollinators for some 50 fruit and vegetable crops, which together form the most nutritious portion of our daily diet. But honeybees also provide us another great gift, one that feeds our brains rather than our bellies, for inside each teeming beehive is an exemplar of a community whose members succeed in working together to achieve shared goals. We will see that these little six-legged beauties have something to teach us about building smoothly functioning groups, especially ones capable of exploiting fully the power of democratic decision making.

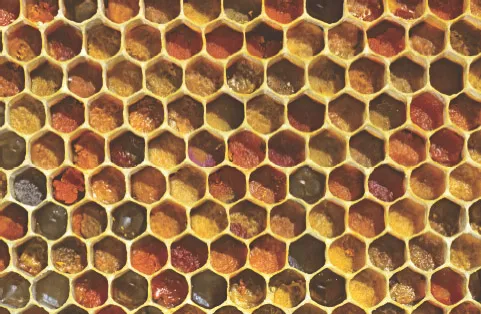

Our lessons will come from just one species of honeybee, Apis mellifera, the best-known insect on the planet. Originally native to western Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe, it is now found in temperate and tropical regions throughout the world thanks to the dispersal efforts of its human admirers. It is a bee that is beautifully social. We can see this beauty in their nests of golden combs, those exquisite arrays of hexagonal cells sculpted of thinnest beeswax (fig. 1.1). We can see it further in their harmonious societies, wherein tens of thousands of worker bees, through enlightened self-interest, cooperate to serve a colony’s common good. And in this book, we will see the social beauty of honeybees vividly, and in fine detail, by examining how a colony achieves near-perfect accuracy when it selects its home.

Fig. 1.1 A comb built of beeswax sculpted into hexagonal cells and filled with pollen from various species of plants

Choosing the right dwelling place is a life-or-death matter for a honeybee colony. If a colony chooses poorly, and so occupies a nest cavity that is too small to hold the honey stores it needs to survive winter, or that provides it with poor protection from cold winds and hungry marauders, then it will die. Given the vital importance of choosing a suitably roomy and snug homesite, it is not surprising that a colony’s choice of its living quarters is made not by a few bees acting alone but by several hundred bees acting collectively. This book is about how this sizable search committee almost always makes a good choice. We will uncover the means by which these house-hunting bees scour the neighborhood for potential nest sites, report the news of their discoveries, conduct a frank debate about these options, and ultimately reach an agreement about which site will be their colony’s new dwelling place. In short, we will examine the ingenious workings of honeybee democracy.

There is one common misunderstanding about the inner operations of a honeybee colony that I must dispel at the outset, namely that a colony is governed by a benevolent dictator, Her Majesty the Queen. The belief that a colony’s coherence derives from an omniscient queen (or king) telling the workers what to do is centuries old, tracing back to Aristotle and persisting until modern times. But it is false. What is true is that a colony’s queen lies at the heart of the whole operation, for a honeybee colony is an immense family consisting of the mother queen and her thousands of progeny. It is also true that the many thousands of attentive daughters (the workers) of the mother queen are, ultimately, all striving to promote her survival and reproduction. Nevertheless, a colony’s queen is not the Royal Decider. Rather, she is the Royal Ovipositer. Each summer day, she monotonously lays the 1,500 or so eggs needed to maintain her colony’s workforce. She is oblivious of her colony’s ever-changing labor needs—for example, more comb builders here, fewer pollen foragers there—to which the colony’s staff of worker bees steadily adapts itself. The only known dominion exercised by the queen is the suppression of rearing additional queens. She accomplishes this with a glandular secretion, called “queen substance,” that workers contacting her pick up on their antennae and distribute to all corners of the hive. In this way, these workers spread the word that their mother queen is alive and well, hence there is no need to rear a new queen. So the mother queen is not the workers’ boss. Indeed, there is no all-knowing central planner supervising the thousands and thousands of worker bees in a colony. The work of a hive is instead governed collectively by the workers themselves, each one an alert individual making tours of inspection looking for things to do and acting on her own to serve the community. Living close together, connected by the network of their shared environment and a repertoire of signals for informing one another of urgent labor needs—for example, dances that direct foragers to flowers brimming with sweet nectar—the workers achieve an enviable harmony of labor without supervision.

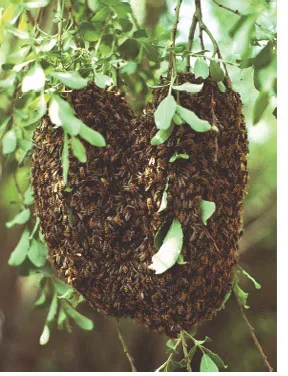

Collective Intelligence

This book focuses on what I believe is the most wondrous example of how the multitude of bees in a hive, much like the multitude of cells in a body, work together without an overseer to create a functional unit whose abilities far transcend those of its constituents. Specifically, we will examine how a swarm of honeybees achieves a form of collective intelligence in the choice of its home. As will be described in chapter 2, the bees’ process of house hunting unfolds in late spring and early summer, when colonies become overcrowded in their nesting cavities (bee hives and tree hollows) and then cast a swarm. When this happens, about a third of the worker bees stay at home and rear a new queen, thereby perpetuating the mother colony, while the other two-thirds of the workforce—a group of some ten thousand—rushes off with the old queen to create a daughter colony. The migrants travel only 30 meters (about 100 feet) or so before coalescing into a beardlike cluster, where they literally hang out together for several hours or a few days (fig. 1.2). Once bivouacked, the swarm will field several hundred house hunters to explore some 70 square kilometers (30 square miles) of the surrounding landscape for potential homesites, locate a dozen or more possibilities, evaluate each one with respect to the multiple criteria that define a bee’s dream home, and democratically select a favorite for their new domicile. The bees’ collective judgment almost always favors the site that best fulfills their need for sufficiently spacious and highly protective accommodations. Then, shortly after completing their selection process, the swarm bees implement their choice by taking flight en masse and flying straight to their new home, usually a snug cavity in a tree a few miles away.

The enchanting story of house hunting by honeybees presents us with two intriguing mysteries. First, how can a bunch of tiny-brained bees, hanging from a tree branch, make such a complex decision and make it well? The solution to this first mystery will be revealed in chapters 3, 4, 5, and 6. Second, how can a swirling ensemble of ten thousand airborne bees steer themselves and stay together throughout the cross-country flight to their chosen home, a journey whose destination is typically a small knothole in an inconspicuous tree in a remote forest corner? The solution to this second mystery will be revealed in chapters 7 and 8.

Fig. 1.2 A swarm of honeybees, with approximately ten thousand worker bees and one queen bee.

We will see that the 1.5 kilograms (3 pounds) of bees in a honeybee swarm, just like the 1.5 kilograms (3 pounds) of neurons in a human brain, achieve their collective wisdom by organizing themselves in such a way that even though each individual has limited information and limited intelligence, the group as a whole makes first-rate collective decisions. This comparison between swarms and brains might seem superficial, but there is real substance here. Over the last two decades, while other sociobiologists and I have been analyzing the behavioral mechanisms of decision making by insect societies, neurobiologists have been investigating the neuronal basis of decision making by primate brains. It turns out there are intriguing similarities in the pictures that have emerged from these two independent lines of study. For example, the studies of individual neuron activity associated with the eye-movement decisions in monkey brains and the studies of individual bee activity associated with nest-site decisions in honeybee swarms have both found that the decision-making process is essentially a competition between alternatives to accumulate support (e.g., neuron firings and bee visits), and the alternative that is chosen is the one whose accumulation of support first surpasses a critical threshold. Consistencies like these suggest that there are general principles of organization for building groups far smarter than the smartest individuals in them. We will explore these principles in chapter 9, where we will compare the decision-making mechanisms of bee swarms and primate brains, and in chapter 10, where we will review the lessons that have been learned from the bees about how to structure a group so that it functions as a smart decision maker.

Group decisions by humans are widespread and important, whether they are small-scale (e.g., agreements made among friends and colleagues), medium-scale (e.g., choices made in democratic town meetings), or large-scale decisions (e.g., national elections or international agreements). Not surprisingly, humans have puzzled over how to optimize group decision making for millennia, at least since Plato’s The Republic (360 BC) and no doubt long before, and yet many questions remain open about how humans can improve social choice. In chapter 10, I will offer some suggestions, what I call “Swarm Smarts” because they have been learned from the bees, on how human groups can organize themselves to improve their decision making. The American essayist Henry David Thoreau expressed skepticism about the wisdom of crowds when he wrote, “The mass never comes up to the standard of its best member, but on the contrary degrades itself to a level with the lowest.” The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was even more negative about group intelligence when he wrote, “Madness is rare in individuals—but in groups…it is the rule.” Certainly there are many examples of groups making lousy decisions—think of stock market bubbles or of deadly stampedes from burning buildings—but the reality of honeybee swarms making good decisions shows us that there really are ways to endow a group with a high collective IQ.

Dancing Bees

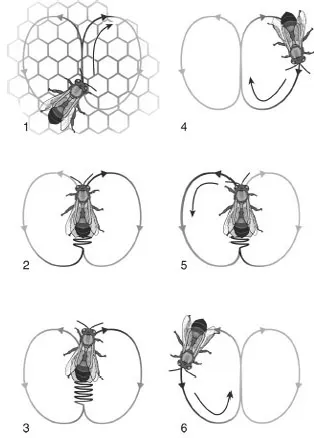

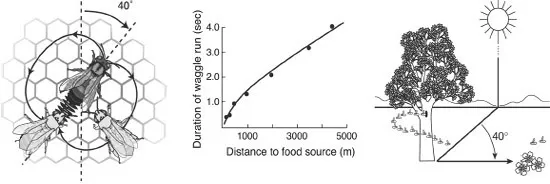

The scientific story told in this book started in Germany almost seventy years ago, in the summer of 1944, when a distinguished professor of zoology at the University of Munich, Karl von Frisch, made a revolutionary discovery for which he would eventually receive the Nobel Prize: an insect, the worker honeybee, can inform her hive mates of the direction and distance to a rich food source by means of dance behavior. Von Frisch had already known for nearly thirty years that when a lone forager finds a rich source of nectar, she returns excitedly to her hive and performs a conspicuous “waggle dance.” In performing this eye-catching behavior, the dancer walks straight ahead on the vertical surface of a comb, waggling her body from side to side, then she stops the “waggle run” and turns left or right to make a semicircular “return run” back to her starting point, whereupon she produces another waggle run followed by another return run, and so on (fig. 1.3). Each waggle dance consists, therefore, of a series of dance circuits, and each dance circuit contains a waggle run and a return run. Von Frisch also knew that a bee may continue dancing for some seconds or even some minutes, all the while trailed by unemployed foragers that, in his own words, “take part in each of her manoeuvrings so that the dancer herself, in her madly wheeling movements, appears to carry behind her a perpetual comet’s tail of bees.” Furthermore, he knew well that after a dance-follower has tripped along behind a dancer throughout several circuits of her dance, she rushes out of the hive to search for the bonanza announced by the dancing bee. But before 1944, von Frisch thought that the only thing the dance-followers learned from the dancer was the fragrance of the flowers she had visited—which they detected by holding their antennae close to the dancer to smell the floral scents adhering to her body—and that upon leaving the hive the newly aroused bees simply searched in ever-expanding circles until they discovered flowers with the memorized fragrance. What von Frisch discovered in 1944 was nearly incredible: the dance-followers did not search for flowers with the matching scent everywhere around the hive, but only in the vicinity of where the dancer had foraged, even if she had foraged in a remote spot, such as along a shady lakeside trail far from the hive. Without a doubt, the newcomers were somehow acquiring from the successful forager information about food-source location as well as food-source scent. Could this location information be communicated inside the hive, by means of the bees’ dances?

Fig. 1.3 The movement pattern of a worker bee performing a waggle dance on the vertical surface of a comb inside her colony's hive. The bee is shown performing two circuits of the waggle dance.

The answer turned out to be a definitive yes. In the summer of 1945, amid the chaos in Europe following the end of World War II, von Frisch returned to his dancing bees, now observing their movements more closely than ever before, examining them for clues that would help him solve his mystery. He discovered that when a bee performs a waggle run inside a dark hive, she produces a miniaturized reenactment of her recent flight outside the hive over sunlit countryside, and in this way indicates the location of the rich food source she has just visited (fig. 1.4). Her encoding of the information about food-source location works as follows. The duration of the waggle run—made conspicuous despite the darkness by the dancer audibly buzzing her wings while waggling her body—is directly proportional to the length of the outward journey. On average, one second of the combined body-waggling/wing-buzzing represents some 1,000 meters (six-tenths of a mile) of flight. And the angle of the waggle run, relative to straight up on the vertical comb, represents the angle of the outward journey relative to the direction of the sun. Thus, for example, if a successful forager walks directly upward while producing a waggle run, she indicates that “the feeding place is in the same direction as the sun.” Or, if the waggling bee heads 40 degrees to the right of vertical, her message is, “The feeding place is 40 degrees to the right of the sun,” as shown in figure 1.4. Perhaps most remarkably, the bees that follow a dancer, monitoring her waggle runs, are able to decode her dance and put her flight instructions into action.

Fig. 1.4 How a dancing bee encodes information about the distance and direction to a rich patch of flowers. Distance coding: The duration of each waggle run is proportional to the length of the outbound flight. Direction coding: Outside the hive the bee notes the angle of her outbound flight relative to the sun's direction, and then inside the hive she orients her waggle runs at the same angle relative to straight up on the comb. Two followers are acquiring the dancing bee's information

While von Frisch was deciphering the secret message of the waggle dance, he was also supervising a young graduate student, named Martin Lindauer, who was to prove von Frisch’s most gifted disciple in revealing the inner workings of honeybee colonies (fig. 1.5). Lindauer is an especially important figure in this book, for he pioneered the study of honeybee democracy as practiced in a bee swarm choosing its home.

Fig.1.5 Karl von Frisch (elderly gentleman, center), Martin Lindauer (young man, leftmost), and other students as they prepare to perform an experiment with the bees, circa 1952.

Lindauer was born in a tiny village in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps, the next to youngest of 15 children in a poor farming family. Here he grew up close to nature—including the bees in his father’s hives—but he was also an outstanding student and won a scholarship to a distinguished boarding school in Landshut, Germany. In April 1939, eight days after his high school graduation, he was drafted into Hi...