![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Forcible Regime Promotion,

Then and Now

We are led, by events and common sense, to one conclusion: The survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands. The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world. America’s vital interests and our deepest beliefs are now one.

—George W. Bush, January 2005

“REGIME CHANGE”: THE UNGAINLY PHRASE was once a technical neologism used by social scientists to signify the alteration of a country’s fundamental political institutions. Now, around the world, it is a political term, and a polarizing one. For the verb “change” has come to imply the coercion of outside powers.1 Regime change requires a regime changer, and in Afghanistan and Iraq the changer-in-chief has been the United States.

America’s costly efforts to democratize these countries have continued under the presidency of Barack Obama, but President George W. Bush’s Second Inaugural Address remains the most striking effort to frame and justify America as regime changer. Bush’s critics, of course, were not impressed by the speech. The Iraq regime change in particular was not going well and seemed destined to end badly. The critics were legion, but they were not united. Some, the realists, thought Bush’s policy of promoting democracy by force to be radical and moralistic, innocent of the essential nature of international relations, bound to bring on disaster. It can never be the case that America’s “deepest beliefs” and “vital interests” are the same. A fundamental realist tenet is that states must always trade off some measure of their values for the sake of the national interest. Bush was departing dangerously from established prudent statecraft. He not only talked in idealistic language, he believed and acted upon it.

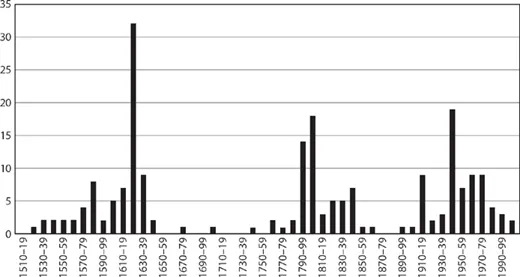

Setting aside, for the moment, the merits of these U.S-led wars—and there is much to criticize about each—are the realists correct? Are these wars really so extraordinary? Do states only rarely use force to try replace other states’ domestic regimes? Figure 1.1 suggests otherwise.2

The figure depicts the frequency by decade of uses of force by one state to alter or preserve the domestic regime of another state over the past five hundred years. By regime I mean not simply a state’s government or rulers but, following David Easton and his colleagues, its “institutions, operational rules of the game, and ideologies (goals, preferred rules, and preferred arrangements among political institutions).”3 Some of these were what I call ex ante promotions, in which the chief object was regime promotion. Others were what I call ex post promotions, in which the initial attack was for other reasons—typically to gain strategic assets in wartime—and then, following conquest, the occupying military imposed a regime on the occupied state. Some cases are difficult to classify as exclusively ex ante or ex post. The total number of cases is 209; tables listing each promotion are below. Figure 1.1 represents raw numbers and does not control for the number of states in the international system. It also treats the estates of the Holy Roman Empire as states (see chapter 4), which affects the numbers prior to the empire’s abolition in 1806. It tallies only uses of force for the purpose of altering or preserving a domestic regime; it ignores other means of promotion such as economic inducements, threats, covert action, and diplomacy. The target of regime promotion must be allowed to remain (nominally) a state; I do not include conquests that incorporate targets into empires.

Figure 1.1 Foreign impositions of domestic institutions, 1510–2010

Over the centuries, states have forcibly promoted domestic regimes in Europe, Asia, Latin America, and Africa. Depending upon time and place, they have promoted established Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Calvinism; absolute monarchy, constitutional monarchy, and republicanism; communism, fascism, and liberal democracy; and secularism and Islamism. As I discuss below and throughout this book, cases of forcible regime promotion tend to cluster in time and space. The temporal and spatial patterns in the data tell us much about why states practice this particular policy. But the initial point is simply that forcible regime promotion is common enough that we can call it a normal tool of statecraft. Tables 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3, which appear later in this chapter, list each case.

President Bush faced a second set of critics, who took a less tragic view of world politics. His more liberal or idealist opponents insisted that Bush was in fact a cold and disingenuous realist. The rhetoric about freedom and tyranny masked the familiar self-aggrandizement of the American empire. The United States was replaying the old Anglo-Russian Great Game in Afghanistan and making a play in Iraq for Persian Gulf oil and the subordination of Iran. Democratization was a cover for domination.

But even if it is the case that the administration was acting out of pure self-interest in Iraq or Afghanistan, does it follow that Bush and his advisers did not care whether these countries ended up with democratic or constitutional regimes? If not, they certainly went to great lengths to continue the charade. It would have been much more efficient to set up new, more pliable dictators in place of the old ones. Figure 1.1 suggests that there have been scores of cases in which governments made calculations similar to those of Bush, spending dear resources to change a target state’s regime and not simply its leadership. In fact, as I make clear in the chapters that follow, governments or rulers who use force to promote an ideology abroad nearly always believe it is in their interests to do so. They believe that they are shaping their foreign or domestic environment, or both, in their favor. Furthermore, although it is an open question whether the Bush administration was correct regarding Iraq, history shows that governments who try to impose regimes on other countries are usually right, at least in the short term. Conditions sometimes arise under which it is rational for a government to use force to change or preserve another country’s domestic regime; when an intervention succeeds, the government that did the promotion is better off, the country it governs more secure.

We have here, then, something much larger than the Bush Doctrine or the war on terror or an attempt to democratize the Muslim world. We have regularity, a historically common state practice, which is surprisingly under-studied. It is a highly consequential practice, for it involves the use of force. It entails violations of sovereignty, a building block of the modern international system.4 It is not a trivial practice or an afterthought, but a costly policy—costly not simply in its use of the promoting state’s resources but in the way it can exacerbate international conflicts. Indeed, as will become evident, forcible regime promotion can be a self-multiplying phenomenon, making great-power relations more violent and dangerous. A Habsburg invasion of Bohemia in 1618 to suppress a Protestant uprising spiraled into the Thirty Years’ War. In 1830, an Anglo-French intervention on behalf of the liberal Belgian revolt alienated Prussia, Austria, and Russia, and raised the prospect of great-power war. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 to shore up a communist regime caused the thawing Cold War to return to a deep freeze. Forcible regime promotion can create all manner of problems in world politics even as it mitigates short-term difficulties. On the other hand, foreign regime imposition can yield benefits to the states that practice it by helping them entrench their hegemony.5 It can also produce periods of stable relations among great powers, as in the decades following 1648, 1815, and 1945.6 So how do we explain this regularity? What causes forcible regime promotion?

Governments tend to impose regimes in regions of the world where there is already deep disagreement as to the best form of government. They also tend to do it in moments when elites across societies in the target’s region are sharply dividing along ideological lines, a condition I call transnational ideological polarization. Ideological polarization means that elites temporarily have unusually strong preferences for either ideology A or competing ideology B and strong preferences for aligning with states that exemplify their favored ideology. Such polarization can present governments with either or both of two incentives to use force to promote regimes. The first is what I call external security or a government’s desire to alter or maintain the international balance of power in its favor. When elites across states are highly polarized by ideology, a government of a great power can make a target state into an ally, or keep it as one, by promoting the right ideology. The great-power ruler may also have a rival that exemplifies the competing ideology and has a parallel incentive to promote that ideology in the target; in such cases, each great power has an incentive to pre-empt the other by promoting its ideology.

The second incentive I call internal security, or a government’s desire to strengthen its power at home. Internal security is at play when transnational ideological polarization reaches into the great power itself and jeopardizes the government’s hold on power by rousing opposition to its regime. Precisely because the threat is transnational, the government can degrade it by attacking it abroad as well as at home. By suppressing an enemy ideology abroad, it can remove a source of moral and perhaps material support for enemy ideologues at home. It can make domestic ideological foes look disloyal or unpatriotic if they oppose this use of force. It can halt or reverse any impression elites may have that the enemy ideology has transnational momentum.

By no means has transnational ideological polarization been a constant feature of the past half-millennium; at many times elites cared relatively little about regime loyalties or ideologies. What triggers polarization, and hence forcible regime promotions, is either of two types of event. The first is regime instability in one or more states in the region. By regime instability I mean a sharp increase in the probability that one regime will be replaced by another via revolution, coup d’état, legitimate government succession, or other means; or a fresh regime change that has yet to be consolidated. Regime instability triggers transnational ideological polarization via demonstration effects, or the increasing plausibility among elites that other countries could follow suit by likewise undergoing regime instability. The second type of triggering event is a great-power war. A great-power war may have little to do initially with ideology, but if the belligerents exemplify competing regime types then their fighting will be seen by elites across societies as implicating the larger ideological struggle, and those elites will tend to polarize over ideology. Many of the promotions in figure 1.1 were triggered by regime instability; many others, mostly captured by the tall bars, tend to come during and after great-power wars.

The transnational nature of ideological polarization is crucial: elites across countries segregate simultaneously, and in reaction to one another, over ideology. Furthermore, they tend to polarize over a set of two or three ideologies that is fixed for many decades. Indeed, figure 1.1 depicts three long waves of forcible regime promotion, and these roughly correspond to three long transnational contests over the best regime. The first wave took place in Central and Western Europe between the 1520s and early eighteenth century, and pitted established Catholicism against various forms of established Protestantism. The second took place in Europe and the Americas between the 1770s and late nineteenth century; the regimes in question were republicanism, constitutional monarchy, and absolute monarchy. The third took place over most of the world between the late 1910s and 1980s, and the antagonists were communism, liberalism, and (until 1945) fascism. Today, a fourth struggle runs through the Muslim world, a struggle pitting secularism against various forms of Islamism. It is that struggle that helped pull the Bush administration into using force in Iraq and Afghanistan. But figure 1.1 also shows historical gaps, when no such contest over the best regime cut across states. During those gaps states used force regularly, but not to impose regimes on other states.

That forcible regime promotion occurs in such patterns—long waves over many decades, followed by long gaps—and that within each long wave the regimes being promoted are within the same fixed set, requires that we push the explanation further, to a macro-level of analysis. What explains these long waves of promotion? I argue that during each of these long waves a social structure was in place in the regions in question that heavily conditioned the preferences and actions of elites, including rulers of states. That structure was the transnational regime contest itself. Elites held a general understanding that there was such a contest stretching across their region, that it was consequential, and that at some point they might have to choose sides. It was not simply that some states had one regime and others had another, for that is typical in world politics. What made a contest was the existence across states of networks of elites who wanted to spread one regime and roll others back. These I ...