![]()

1

PROLOGUE: THE BIG PICTURE

1.1 In the Beginning

As the Universe expands, galaxies get separated from one another, and the average density of matter over a large volume of space is reduced. If we imagine playing the cosmic movie in reverse and tracing this evolution backward in time, we can infer that there must have been an instant when the density of matter was infinite. This moment in time is the “Big Bang,” before which we cannot reliably extrapolate our history. But even before we get all the way back to the Big Bang, there must have been a time when stars like our Sun and galaxies like our Milky Way* did not exist, because the Universe was denser than they are. If so, how and when did the first stars and galaxies form?

Primitive versions of this question were considered by humans for thousands of years, long before it was realized that the Universe expands. Religious and philosophical texts attempted to provide a sketch of the big picture from which people could derive the answer. In retrospect, these attempts appear heroic in view of the scarcity of scientific data about the Universe prior to the twentieth century. To appreciate the progress made over the past century, consider, for example, the biblical story of Genesis. The opening chapter of the Bible asserts the following sequence of events: first, the Universe was created, then light was separated from darkness, water was separated from the sky, continents were separated from water, vegetation appeared spontaneously, stars formed, life emerged, and finally humans appeared on the scene.* Instead, the modern scientific order of events begins with the Big Bang, followed by an early period in which light (radiation) dominated and then a longer period dominated by matter, leading to the appearance of stars, planets, life on Earth, and eventually humans. Interestingly, the starting and end points of both versions are the same.

1.2 Observing the Story of Genesis

Cosmology is by now a mature empirical science. We are privileged to live in a time when the story of genesis (how the Universe started and developed) can be critically explored by direct observations. Because of the finite time it takes light to travel to us from distant sources, we can see images of the Universe when it was younger by looking deep into space through powerful telescopes.

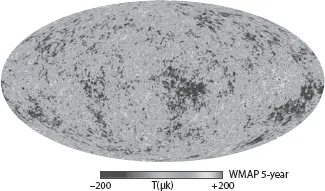

Figure 1.1. Image of the Universe when it first became transparent, 400 thousand years after the Big Bang, taken over five years by the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) satellite (http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/). Slight density inhomogeneities at the level of one part in ~105 in the otherwise uniform early Universe imprinted hot and cold spots in the temperature map of the cosmic microwave background on the sky. The fluctuations are shown in units of μK, with the unperturbed temperature being 2.73 K. The same primordial inhomogeneities seeded the large-scale structure in the present-day Universe. The existence of background anisotropies was predicted in a number of theoretical papers three decades before the technology for taking this image became available.

Existing data sets include an image of the Universe when it was 400 thousand years old (in the form of the cosmic microwave background in figure 1.1), as well as images of individual galaxies when the Universe was older than a billion years. But there is a serious challenge: in between these two epochs was a period when the Universe was dark, stars had not yet formed, and the cosmic microwave background no longer traced the distribution of matter. And this is precisely the most interesting period, when the primordial soup evolved into the rich zoo of objects we now see. How can astronomers see this dark yet crucial time?

The situation is similar to having a photo album of a person that begins with the first ultrasound image of him or her as an unborn baby and then skips to some additional photos of his or her years as teenager and adult. The late photos do not simply show a scaled-up version of the first image. We are currently searching for the missing pages of the cosmic photo album that will tell us how the Universe evolved during its infancy to eventually make galaxies like our own Milky Way.

The observers are moving ahead along several fronts. The first involves the construction of large infrared telescopes on the ground and in space that will provide us with new (although rather expensive!) photos of galaxies in the Universe at intermediate ages. Current plans include ground-based telescopes which are 24–42m in diameter, and NASA’s successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope. In addition, several observational groups around the globe are constructing radio arrays that will be capable of mapping the three-dimensional distribution of cosmic hydrogen left over from the Big Bang in the infant Universe. These arrays are aiming to detect the long-wavelength (redshifted 21-cm) radio emission from hydrogen atoms. Coincidentally, this long wavelength (or low frequency) overlaps with the band used for radio and television broadcasting, and so these telescopes include arrays of regular radio antennas that one can find in electronics stores. These antennas will reveal how the clumpy distribution of neutral hydrogen evolved with cosmic time. By the time the Universe was a few hundreds of millions of years old, the hydrogen distribution had been punched with holes like swiss cheese. These holes were created by the ultraviolet radiation from the first galaxies and black holes, which ionized the cosmic hydrogen in their vicinity.

Theoretical research has focused in recent years on predicting the signals expected from the above instruments and on providing motivation for these ambitious observational projects. In the subsequent chapters of this book, I will describe the theoretical predictions as well as the observational programs planned for testing them. Scientists operate similarly to detectives: they steadily revise their understanding as they collect new information until their model appears consistent with all existing evidence. Their work is exciting as long as it is incomplete.

At a young age I was attracted to philosophy because it addresses the most fundamental questions we face in life. As I matured to an adult, I realized that science has the benefit of formulating a subset of those questions that we can make steady progress on answering, using experimental evidence as a guide.

1.3 Practical Benefits from the Big Picture

I get paid to think about the sky. One might naively regard such an occupation as carrying no practical significance. If an engineer underestimates the strain on a bridge, the bridge may collapse and harm innocent people. But if I calculate incorrectly the evolution of galaxies, these mistakes bear no immediate consequence for the daily life of other people. Is this really the case?

The same engineer who designs bridges would be the first to correct this naive misconception. Newton arrived at his fundamental laws by studying the motion of planets around the Sun, and these laws are now used to build bridges and many other products. Einstein’s general theory of relativity was developed to describe the cosmos but is also essential for achieving the required precision in modern navigation or global positioning systems (GPSs) used for both civil and military applications.

But there is a bigger context to the significance of the study of the Universe, namely, cosmology. The big picture gives us the practical advantage of having a more informed view of reality. Consider the weather, for example. It is a natural tendency for people to complain about the harsh weather in particular locations or seasons when rain or snow are common. Some might even associate the weather patterns with a divine entity that reacts to human actions. But if one observes an aerial photo from a satellite, it is easy to understand the origins of the weather patterns in particular locations. The data can be fed into a computer simulation that uses the laws of physics to forecast the weather in advance. With a global understanding of weather and climate patterns one obtains a better sense of reality.

The biggest view we can have is that of the entire Universe. In order to have a balanced worldview we must understand the Universe. When I look up into the dark clear sky at night from the porch of my home in the town of Lexington, Massachusetts, I wonder whether we humans are too often preoccupied with ourselves. There is much more to the Universe than meets the eye around us on Earth.

* A star is a dense, hot ball of gas held together by gravity and powered by nuclear fusion reactions. A galaxy consists of a luminous core made of stars or cold gas surrounded by an extended halo of dark matter (see section 2.7).

* Of course, it is possible to interpret the biblical text in many possible ways. Here I focus on a plain reading of the original Hebrew text.

![]()

2

STANDARD COSMOLOGICAL MODEL

2.1 Cosmic Perspective

In 1915 Einstein came up with the general theory of relativity. He was inspired by the fact that all objects follow the same trajectories under the influence of gravity (the so-called equivalence principle, which by now has been tested to better than one part in a trillion), and realized that this would be a natural result if space-time is curved under the influence of matter. He wrote down an equation describing how the distribution of matter (on one side of his equation) determines the curvature of space-time (on the other side of his equation). He then applied his equation to describe the global dynamics of the Universe.

Back in 1915 there were no computers available, and Einstein’s equations for the Universe were particularly difficult to solve in the most general case. It was therefore necessary for Einstein to alleviate this difficulty by considering the simplest possible Universe, one that is homogeneous and isotropic. Homogeneity means uniform conditions everywhere (at any given time), and isotropy means the same conditions in all directions when looking out from one vantage point. The combination of these two simplifying assumptions is known as the cosmological principle.

The universe can be homogeneous but not isotropic: for example, the expansion rate could vary with direction. It can also be isotropic and not homogeneous: for example, we could be at the center of a spherically symmetric mass distribution. But if it is isotropic around every point, then it must also be homogeneous.

Under the simplifying assumptions associated with the cosmological principle, Einstein and his contemporaries were able to solve the equations. They were looking for their “lost keys” (solutions) under the “lamppost” (simplifying assumptions), but the real Universe is not bound by any contract to be the simplest that we can imagine. In fact, it is truly remarkable in the first place that we dare describe the conditions across vast regions of space based on the blueprint of the laws of physics that describe the conditions here on Earth. Our daily life teaches us too often that we fail to appreciate complexity, and that an elegant model for reality is often too idealized for describing the truth (along the lines of approximating a cow as a spherical object).

Back in 1915 Einstein had the wrong notion of the Universe; at the time people associated the Universe with the Milky Way galaxy and regarded all the “nebulae,” which we now know are distant galaxies, as constituents within our own Milky Way galaxy. Because the Milky Way is not expanding, Einstein attempted to reproduce a static universe with his equations. This turned out to be possible after adding a cosmological constant, whose negative gravity would exactly counteract that of matter. However, he soon realized that this solution is unstable: a slight enhancement in density would make the density grow even further. As it turns out, there are no stable static solution to Einstein’s equations for a homogenous and isotropic Universe. The Universe must be either expanding or contracting. Less than a decade later, Edwin Hubble discovered that the nebulae previously considered to be constituents of the Milky Way galaxy are receding away from us at a speed v that is proportional to their distance r, namely, v = H0r with H0 a spatial constant (which could...