![]()

PART ONE

Temporal Latitudes

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Augustan American Literature:

An Aesthetics of Extravagance

RESTORATION LEGACIES: COOK AND BYRD

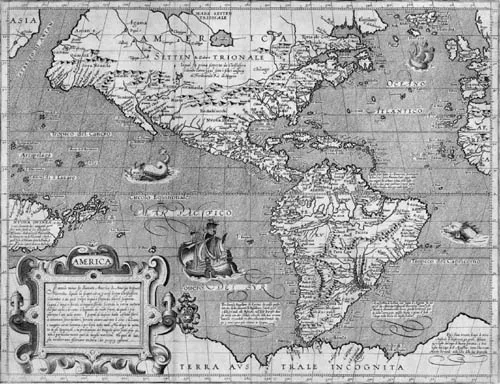

As Karen Ordahl Kupperman has noted, the study of geography “blossomed” in Europe after Christopher Columbus’s voyages of the 1490s (1), with the New World becoming central to discursive treatments of space that moved away from medieval symbolic maps with Jerusalem at their center. Under the influence of navigation, exploration, and, by extension, the allure of wealth, there was increasing interest in how different spatial perspectives could be aligned with new ways of seeing the world. The ancient Roman geographer and astronomer Ptolemy enjoyed his own renaissance at this time, and the force of Ptolemy’s description of geography as a form of painting can be seen in the artistic composition of the map of America produced by the Italian Arnoldo di Arnoldi in Siena around 1600 (figure 4).1 Arnoldi’s interest here is in framing America by juxtaposing it with other parts of the world: we see Britain, France, and Spain in the top right corner of the map, Iceland in the far north, Asia in the top left corner, New Guinea in the bottom left, and what was then known as “Terra Australe Incognita,” the unknown southern land, at the bottom. Working a hundred years after Columbus, Arnoldi’s concern was to represent America cartographically in relation to a global picture of exploration, to position America on the world map.

Because of the nationalist emphasis that has traditionally circumscribed the study of early American literature, however, these more variegated geographical and global dimensions have often been excluded from the way the subject has been constructed. As noted in the introduction, the very notion of an “early” period is itself a prolepsis, a projection back from a nationalist idea of American literature in order to uncover supposed precursors or foreshadowings of later events.2 Moreover, as Emory Elliott observed (6), it is only since about 1970 that American literature of the prerevolutionary period has been taken seriously at all; the old canard that American literature began in the 1830s with a cultural declaration of independence by Ralph Waldo Emerson has gradually been replaced by an increasing recognition of the historical complexity and aesthetic variety of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century work. Nevertheless, as David Shields has remarked (“Aching”), no period in American literature remains still so neglected as that between 1700 and 1765, while Sandra M. Gustafson makes the point that there is a need for more dialogue between early Americanists and U.S. Americanists about how the entire field might position itself in relation to issues such as empire and transnationalism, questions that traverse the subject’s conventional chronological and spatial parameters (107).

Figure 4. Map of America by Arnoldo di Arnoldi (ca. 1600). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Although T. S. Eliot was complaining as far back as 1919, in his review of the first Cambridge History of American Literature, about the disproportionate homage paid to New England writers at the expense of writers from the South such as Edgar Allan Poe or Mark Twain, much of the twentieth-century work on prerevolutionary American culture was shaped by Perry Miller’s monumental intellectual histories of what he called “the New England mind.” Equally influential have been Sacvan Bercovitch’s studies of the 1970s, The American Jeremiad and The Puritan Origins of the American Self, the latter arguing for the nonconformist, apocalyptic temper of seventeenth-century Calvinist thought as the progenitor of both nineteenth-century individualism and critical theories of American exceptionalism. Bercovitch’s scholarly legacy subsequently became institutionalized through his role as general editor of the second Cambridge History of American Literature, which published its first volume, on the period 1590 through 1820, in 1994. In this first part of the sequence, Bercovitch chose to finesse the problem of the eighteenth century by incorporating two substantial contributions, one from Robert Ferguson on the “American Enlightenment” after 1750, the other from David Shields titled “British-American Belles Lettres.” The latter is an account of polite literature written and circulated in the early eighteenth-century colonies, drawing upon the brilliant work of textual reclamation in Shields’s first book, Oracles of Empire. The consequence of this strategy, however, was to leave the “Puritan origins” story largely intact. By locating Augustan American literature in the coffeehouses of Maryland and Pennsylvania in the reigns of Queen Anne and the first two King Georges, Bercovitch’s editorial trajectory implicitly reinforced the old idea of a cultural time lag in the colonies, whereby the artistic innovations of Alexander Pope and Joseph Addison were only given expression in America a generation or so later.

One argument I want to make here is that a conception of Augustan American literature might usefully be pushed back into the preceding century, thereby complicating the rather too neat sequence of development whereby seventeenth-century Puritanism is succeeded by a more worldly eighteenth-century idiom. Another argument, one expounded by Thomas Scanlan in his discussion of the “fundamentally anachronistic” American exceptionalist thesis (1), is that the cultural traditions of Britain and America from 1640 onward were much more closely intertwined than has usually been imagined, so that the idea of Augustan literature can be seen to operate on a transatlantic axis in the wake of the English Civil War. As David Norbrook has shown, when Oliver Cromwell was lord protector of the commonwealth in the 1650s he deliberately associated himself with the model of Augustus Caesar, a parallel reinforced by the poet Edmund Waller, who iconographically installed Cromwell as the true heir of both the Roman emperors and the Stuart monarchs (306). Today we tend to associate the idea of Augustan England with the Restoration of monarchy in the 1660s: Francis Atterbury, in his 1690 preface to Waller’s Poems, asked rhetorically “whether, in Charles the Second’s reign, English did not come to its full perfection; and whether it has not had its Augustan Age as well as the Latin” (121). But it is important to recognize how this image of Augustus was politicized and contested in the second half of the seventeenth century and how there were claims for a republican interpretation of the Augustan narrative as well as a monarchical version. Far from being locked into their own isolated world, the New England community was heavily involved and invested in these debates: Sir Henry Vane, who succeeded John Winthrop as governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1636, subsequently returned to England and became one of the parliamentary leaders who was then hanged upon the restoration of Charles II in 1660, while two of Winthrop’s own sons, Stephen and Fitzjohn, fought for Leveller regiments in England during the 1640s.

Despite all this, the legacy of the English Civil War has tended to remain curiously obscure in the annals of what has become known as “early American literature.” As Andrew Delbanco has remarked, Vane himself has been more or less “expunged from the historical record” (114), while the recognition of New England as an immigrant community, with strong ties on both sides of the Atlantic, has in general been overwhelmed by the teleological narrative of American exceptionalism. This is the spirit that would seek to transform history into typology, thereby fulfilling the logic of Winthrop’s sermon “A Model of Christian Charity,” which, in a prefiguration of the book of Revelations, identified America with a separatist city on a hill. In The American Jeremiad, Bercovitch describes seventeenth-century New England as a “community without geographical boundaries” (26), where the biblical prototype of the “story of Israel becomes the background for the act of will which transforms geography into eschatology” (42). But such biblical hypotheses were never universally admitted in seventeenth-century America, not even in the Puritan colonies. Indeed, one useful point of entry into Augustan American literature is to consider the significance of the word plantation itself. This is a word Increase Mather did not care for because he found it too redolent of the vulgar material world: “Let there then be no more Plantations erected in New England where people professing Christianity shall live like Indians,” he wrote in 1676 (Brief History 23); and again, this is Increase Mather in 1689: “Other Plantations were built upon Worldly Interests, but New-England upon that which is purely religious” (Brief Relation 3–4). Yet that kind of sublimation of commerce into piety is precisely what we do not find in other New England writing of the mid-seventeenth century. For example, the anonymous work Good News from New England, published in London in 1648, is interesting precisely because it positions itself textually between various boundaries: between old England and New England, between—as the puns on “new” in the poem’s title suggests—geographical location and scriptural tidings and also formally between prose and poetry. All this befits an environment of “mixt men,” as the poem describes it (5), with “diversity of minds” (6), a scenario in which the “unlevel’d” nature of the landscape fittingly represents a world in which religion and profit keep house together (7). The author writes in his preface to this work: “some Latin and Eloquent phrases I have picked from others, as commonly clowns used to do, yet be sure I am not in jest: for the subject I write of requires in many particulars the most solemn and serious meditation that ever any of like nature have done. Favour my clownship if I prove too harsh, and I shall remain yours.”

To highlight such a notion of “clownship,” betokening an apparently incongruous interpenetration between spirit and matter, is to restore more of a material base to seventeenth-century New England culture. Michelle Burnham, in another example of this desublimating approach, has discussed the economic implications of the Antinomian heresy, looking at ways in which documents of the controversy pun continuously on “good estate,” a phrase that swings ambiguously between “the experience of conversion or election” and the “resonance of property or wealth, of a more specifically economic condition” (343). To trace such double strands is to restore links between American Puritan writing and other cultures in both time and space, since it would suggest affinities between New England and the other more overtly mercantile colonies to the south, as well as implying the significant continuities between Puritan radicalism and its Augustan counterpart. It is important to recognize how Augustan American literature at the turn of the eighteenth century did not involve simply a retreat into the polite world of urban coffeehouses; more importantly, it was dealing with the often fractious nature of relations between the sacred and the secular, along with the fallout from the English Civil War just one generation earlier.

We find a more overt style of “clownship” running through Ebenezer Cook’s long poems The Sot-Weed Factor and Sotweed Redivivus, written in Maryland at the beginning of the eighteenth century. The Sot-Weed Factor: Or, A Voyage to Maryland, first published in London in 1708 and described on its title page as “in Burlesque Verse,” chronicles the adventures of a tobacco “factor” or merchant who comes over to Maryland from England, with the poem being organized around patterns of change, crossing, and transgression. This movement across geographical borders is replicated formally in the poem’s generic transposition from epic to mock-epic. Many of the critical debates around The Sot-Weed Factor, such as they are, have centered on the issue of the kind of lesson the author was hoping readers might infer from his comic narrative, whether he is ridiculing the factor himself or the Americans or both (Egan 388); but this attempt to attribute a specific satiric intention is of less interest than the way Cook’s work adroitly imitates and manipulates the form of Samuel Butler’s long poem Hudibras, published between 1662 and 1677. Crucially, it is not just the metrical form of Hudibras Cook is mirroring in The Sot-Weed Factor. Hudibras, with its colloquial language and clumsy rhymes, seeks specifically to debase the high-flown rhetoric prevalent during the English Civil War, and the powerful effect of Butler’s poem derives from its cynical humor, its description of Presbyterian synods (for example) as “mystical Bear-gardens” (91), and its frequently scatological demystifications of the “Saints” (23) and their idea of “inward Light” (93), so that within the world of Hudibras all comes to appear “Arsieversie” (84). The premise of Butler’s poem is of human culture as a mixed condition where spirit and matter are conjoined by an absurdist dynamic, and it looks back to the years in Britain between 1648 and 1661 as an era when religion became a pretext for the acquisition of power and wealth. The second part of Hudibras includes a long discourse on whipping as a form of self-gratification disguised as the altruistic imposition of order, and Butler’s work is generally scathing about what it takes to be humanity’s proneness to airy forms of self-delusion: the poet remarks in his notebooks how we cannot “draw a true Map of Terra Incognita by mere Imagination” (xxiii). Hudibras is especially hostile to the advocates of a “godly-thorough-Reformation” (7) who seek to deny the material reality of both the natural world and their own body, and he uses the paradoxical structure of mock-epic to force these occluded corporeal impulses back into public view:

This Zelot

Is of a mungrel, diverse kind,

Clerick before, and Lay behind;

A Lawless linsie-woolsie brother,

Half of one Order, half another;

A creature of amphibious nature,

On land a Beast, a Fish in water. (95)

“Linsey-woolsie” is a material woven from a mixture of wool and flax, and this serves to emphasize how the idea of hybridity in Hudibras becomes both a moral and political imperative. The argument put forward by Bruce Ingham Granger, that Hudibras was simply advancing a “high-church, monarchical argument,” is much too one-dimensional (3). The power of the poem, still apparent in parts today, lies in its dark, glittering cynicism, its remorseless reduction of the world to a parade of vanity and self-interest.

Hudibras was very widely read and admired when its first part was published in England in 1662, but as memories of the English Civil War began to fade and the topical references began to lose their immediate resonance, so the poem’s popularity faded. However, one place where the saints still reigned was New England, and Cook’s The Sot-Weed Factor seeks deliberately to transfer the anti-Puritan invective of the post–Civil War era across the Atlantic. Even the language of The Sot-Weed Factor—“Wars of Punk” (27), “ambodexter Quack” (29), and so on—directly recalls Hudibras, and just as Butler’s poem seeks to demystify religious rhetoric, so The Sot-Weed Factor evokes a heterogeneous world of Anglos and Indians, civic politics and economic profit, whose idiom involves, as the poem says, “mixing things Prophane and Godly” (23). Starting as it does with a homage to the “Vagrant Cain” (12), Cook’s poem is predicated on an aesthetic of transgression, of breaking through the boundaries of conventional knowledge so as to explore what might lie on the other side:

To touch that Shoar, where no good Sense is found,

But Conversation’s lost, and Manners drown’d.

I crost unto the other side,

A River whose impetuous Tide,

The Savage Borders does divide . . . (13)

Broke thro’ the Barrs which Nature cast,

And wide unbeaten Regions past. (20)

Geographical exploration thus becomes a corollary here to epistemological extravagance, in that word’s strict etymological sense of moving beyond conventional bounds: Latin extra, outside, and vagari, to wander.

For Cook, then, the form of burlesque itself becomes an ethical intervention, a way of deconstructing the idea of utopian phantoms and inscribing instead a material base for social culture. Following as it does in the footsteps of Hudibras, The Sot-Weed Factor consequently epitomizes John P. McWilliams’s point about the generic proximity of epic to mock-epic in American eighteenth-century poetry: the idea of mock-epic was not to mock the epic, as such, but rather to ridicule human aspirations to epic status, so that the discrepancy between epic form and m...