![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The English Professors of Brazil

ON THE DIASPORIC ROOTS OF THE YORÙBÁ NATION

“My religion is pure Nagô.”

—MÃE ANINHA, founder of the Ilê Opô Afonjá Temple1

ARE HOMELANDS TO DIASPORAS as the past is to the present? Is Africa to the black Americas as the past is to the present? Much in the conventional writing of cultural history would suggest that it is. This chapter both revises existing narrations of African-diaspora cultural history and proposes, at the Afro–Latin American locus classicus of Herskovitsian studies, some nonlinear alternatives to Herskovits’s and others’ visions of diasporas generally. I argue here that slavery and African-American isolation from the major trends of Euro-American culture were probably not the typical conditions under which African-inspired culture flourished in the Americas (see also Matory 2000).

The empirical terrain of this revision is the Jeje-Nagô, or Fòn- and Yorùbá-affiliated, temples of the Brazilian Candomblé religion, and their supposedly West African origins, which have become a locus classicus in the study of African “collective memory,” “retention,” and “continuity” as the mechanisms of community formation and cultural transmission in the African diaspora. These temples are cited more often and with greater certainty than any other African-American institution as proof that African culture has “survived” in the Americas (e.g., Raboteau 1980[1978]; Bastide 1967; Herskovits 1966[1955]:227). The formal and lexical parallels between the Jeje-Nagô Candomblé and the contemporary religions of the West African Fòn and Yorùbá are indeed impressive, as trans-Atlantic researchers M. J. Herskovits, Roger Bastide, William Bascom, Pierre Verger, Mikelle Smith Omari, Robert Farris Thompson, Margaret Drewal, Deoscóredes and Juana Elbein dos Santos, and I have agreed.

One of the sharpest implicit challenges to the Herskovitsian project has come from a leading figure in cultural studies. Although Paul Gilroy’s book The Black Atlantic (1993) borrows extensively from the anthropological and Herskovitsian lexicon (employing such terms as “syncretism,” “creolisation,” “ethnohistory,” and the term “black Atlantic” itself), Gilroy overlooks these debts and appears to dismiss the question of the diaspora’s cultural and historical connection to Africa as “essentialist.” Instead, Gilroy describes the African diaspora primarily in terms of a discontinuous cultural exchange among diverse African-diaspora populations. Drawing examples primarily from the English-speaking black populations of England, the United States, and the Caribbean, Gilroy’s Black Atlantic argues that the shared cultural features of African-diaspora groups generally result far less from shared cultural memories of Africa than from these groups’ mutually influential responses to their exclusion from the benefits of the Enlightenment legacy of national citizenship and political equality in the West.

Gilroy usefully gives new salience to the role of free black Atlantic travelers and of cultural exchanges among freed or free black populations in creating a shared black Atlantic culture and shared black identities that transcend territorial boundaries. This approach is anticipated in Brazilianists’ study of the ongoing, two-way travel and commerce between Brazil and Africa.2 Yet the Brazilianists who briefly attend to the cultural consequences of that travel and commerce for Brazil have tended to assume their preservative or restorative effects on the “memory” of an unchanging African past, rather than their transformative effects on both Brazil and Africa (see R. N. Rodrigues 1935[1900/1896]:169; Bastide 1971[1967]:130; 1978[1960]:165, Elbein dos Santos and Santos 1981[1967]).3

The case to be discussed in this chapter—that is, the historical connections between Africa and what is often described as the most “purely African” religion in the Americas—will demand a reunion of these models of the African diaspora. It suggests that greater space be given to African agency, or deliberate action in making the world (which is neglected in Herskovits’s and Gilroy’s models), and to African cultural history (which is neglected in Gilroy’s alone). Both African agency and African culture have been important in the making of African diaspora culture, but more surprisingly, the African diaspora has at times played a critical role in the making of its own alleged African “base line” as well.4

The following revision of diasporic cultural history is based on the premise that Africa is historically “coeval” (Fabian 1983)—or contemporaneous—with its American diaspora. Herskovitsians and their allies distort important realities when they treat African cultures and practices as the “past,” the “base line,” the “provenience,” the “origin,” and the prototype of cognate American realities. The further premise of this revision is closer to the original sense in which Fabian employed the term “coeval.” The West Africanist ethnographers and folklorists whom African-Americanists have tended to cite for information on the “African origins” of New World practices are no more external to the politics of statecraft and knowledge in colonial Africa than are African-Americanists from the racial politics of the postslavery Americas. Not only traveling black pilgrims, businesspeople, and writers but traveling white writers and photographers, as well as their publications, have long been vehicles of transformative knowledge in the production of what Thompson (1983) and Gilroy (1993) call the “black Atlantic” culture.

I will argue that, aside from the introduction of the “culture” concept shared among E. B. Tylor, Franz Boas, and Boas’s student Melville J. Herskovits, the greatest impulse behind the respectful study of African culture in the Americas occurred at the hands of Africans or, properly speaking, through a dialogue among West Africans and African-American returnees to colonial Lagos, now in Nigeria. I will argue that, to this day, neither African-American lifeways nor the scholarly discussion of them escapes the influence of the Lagosian Cultural Renaissance of the 1890s. Yet few scholars are aware of this movement’s impact. Various literatures have masked its principles as characteristics of a primordial African culture, taken them for granted as natural dimensions of cultural memory, or mistaken them for the arbitrary preferences of Euro-American scholars.

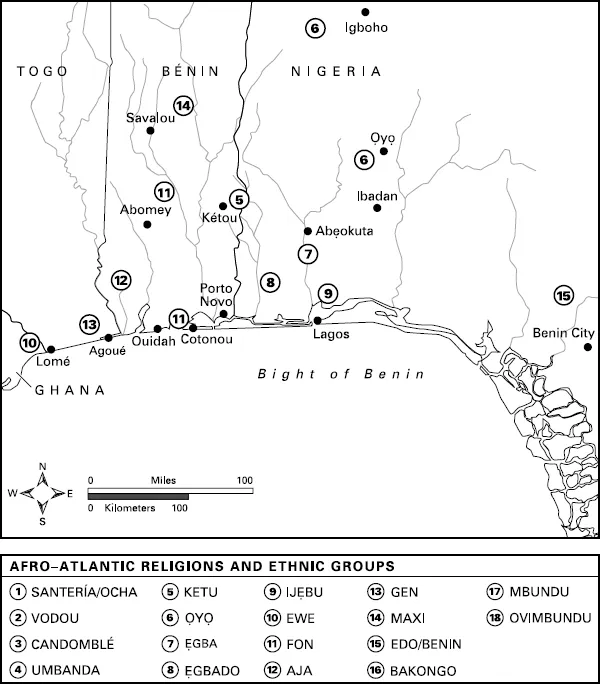

THE BLACK ATLANTIC NATIONS: EXPLAINING THE SUCCESS OF THE YORÙBÁ

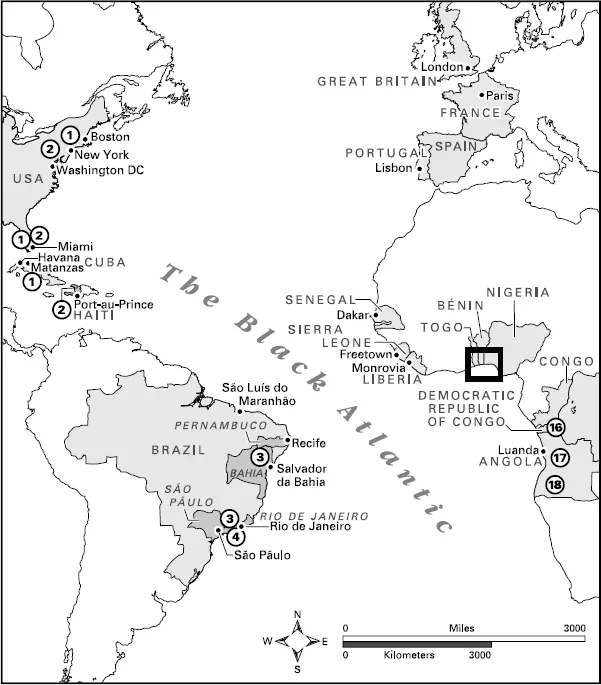

Since the 19th century, one Afro-Latin nation has risen above all the rest—preeminent in size, wealth, grandeur, and international prestige. It is studied, written about, and imitated far more than any other, not only by believers but also by anthropologists, art historians, novelists, and literary critics. The origin and homeland of this trans-Atlantic nation is usually identified as “Yorùbáland,” which is now divided between southwestern Nigeria and the People’s Republic of Bénin on the Gulf of Benin (see maps A and B).5

Yet among its other major metropolises are Havana, Miami, Oyotunji (South Carolina), New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C. These are the lands of the Lucumí. However, this trans-Atlantic nation possesses no greater American metropolis than Salvador da Bahia, which one priestess famously called the “Black Rome” (see map A).6 Located in the Brazilian state of Bahia, this city is usually called “Salvador” or “Bahia” for short and is now the capital of African-inspired religion in Brazil and a pilgrimage site for practitioners and scholars from the United States, the Caribbean, Argentina, France, and Nigeria itself. In Bahia, numerous Candomblé temples identify themselves as members of the nation they call “Quêto,” or “Nagô,” but they have integrated enough ritual practice and vocabulary from Brazil’s second most prestigious nation—the Jeje—for scholars since Raimundo Nina Rodrigues to describe their practice as “Jeje-Nagô” (1988[1905]:215).

Map A. Cultures and capitals of the Black Atlantic world. Map by Adam Weiskind.

Though the equivalence among, for example, the Cuban Lucumís, the Brazilian Nagôs, the Haitian Nagôs, the French West African Nagots, and the British West African Yorùbá was not fully evident in their names, late 19th-century and early 20th-century ethnographers clearly assumed that unity in a way that I will argue was consistent with the interests of a powerful class of black “ethnicity entrepreneurs” (see, e.g., F. Ortiz 1973[1906]:28, 32–33; R. N. Rodrigues 1935[1900/1896]:24; 1945[1905]:175; Ellis 1970[1890]:29–30).7 The trans-Atlantic vicissitudes of the Jeje and Nagô nations, as well as their citizens’ role in reshaping a range of the territorial nations that host them, open this new narration of an old transnationalism.

Map B. Inset—The Bight of Benin. Map by Adam Weiskind.

The dominant narration of African religious history in the Americas comes down to us through Melville J. Herskovits and his legion of followers. It is the story of slaves and of their descendants—separated by time, distance, and cruel fate from Africa—heroically remembering and preserving their ancient ancestral culture. Among the most successful were slaves in Bahia, Brazil (see map A), and their descendants, who, in the late 20th century, practiced what partisan observers call “purely African” rituals and sang in what such observers call “perfect Yorùbá.” According to the received narrative, the descendants of the Yorùbá—members of the Nagô, or Quêto, nation—were so successful at preserving their primordial heritage that certain “houses” call themselves “purely African” or “purely Nagô.”

The apparently extraordinary success of the Brazilian Nagô nation at preserving its African religion is paralleled by the success of the cognate Lucumí nation in Cuba (e.g., Ortiz 1973[1906]:28, 51, 52, 59, 60) and by the success of the Fòn-connected Rada and Mina-Jeje nations in Trinidad (Carr 1989[1955]), Haiti (e.g., Price-Mars 1990[1928]), and São Luís, Brazil (Ferretti 1985). Scholars have conventionally explained the success of the Brazilian Nagô nation in terms of an interaction among multiple factors. However, many of the factors cited rely for their explanatory value on the imputation of general causal mechanisms, nomothetic principles, or inductive patterns that, I will argue, are not borne out by the comparative literature and are not subject to any consensus among the various authors.

First, the Brazilian scholar Raimundo Nina Rodrigues and his followers offered the principal explanation that, at the time of the slave trade, the West African “Nagôs” had possessed a more organized priesthood and a more highly evolved and therefore more complex mythology than had the other equally numerous African peoples taken to Brazil. In Rodrigues’s opinion, the Jejes, or Fòn/Ewè, ran a close second in evolutionary complexity (e.g., R. N. Rodrigues 1945[1905]:342; 1988[1905]:230–31).8

On the contrary, Robert Farris Thompson and Bunseki Fu-Kiau’s discussions of Kongo cosmology suggest that what has come to be called “Yorùbá” religion possessed no monopoly on complexity (e.g., Thompson 1983:101–59). In any case, it is not obvious that more complex religions are more attractive to converts than are less complex ones. Christianity did not replace Greco-Roman religion because of Christianity’s relative mythic complexity or the superior organization of its priesthood. Nor would such an explanation account for the spread of Buddhism and Islam. Whether simpler or more complex than Yorùbá culture, the Central, East, and southern African cultures of the Bantu speakers, including the BaKongo, are the products of a demographic and cultural expansion within Africa that dwarfs the transoceanic influence of the Yorùbá’s ancestors. By the eighth century A.D., the Bantu languages had spread from a small nucleus in what is now Nigeria to Zanzibar, off the coast of East Africa (Curtin et al. 1978:25–30). Bantu speakers now dominate virtually the entire southern half of the African continent and have significantly influenced the music, religion, and language of the Americas as well (e.g., Kubik 1979; Vass 1979; Thompson 1983). Bastide 1978[1960]:60) attributes the decline of Bantu religion in Brazil to what he regards as its nearly exclusive focus on the patriarch’s veneration of dead ancestors and the irrelevance of such a pursuit under American slavery, where the African family and its internal leadership have been torn asunder. Yet ritual negotiation with the spirits of the dead remains a prominent feature of caboclo- and Yorùbá-inspired Egungun worship in Brazil, as well as the Petwo nation of Haiti and the explicitly Bantu-inspired Palo Mayombe religion of Cuba, where the West-Central African–inspired inkices have entered into a powerful moral symbiosis with the West African–inspired orichas (Palmié 2002). Dealings with the dead, including Bantu-inspired ones, were adaptable to a wide range of African-American sacred projects. There is no systematic contradiction, across American locales, between cults of the dead and the regime of slavery.

Verger spearheaded a less popular, nonevolutionary explanation for Nagô success, attributing the strength of Yorùbá influence to “the recent and massive arrival of this people” in Bahia and to the presence of numerous Yorùbá captives “originating from a high social class, as well as priests conscious of the value of their institutions and firmly attached to the precepts of their religion” (Verger 1976[1968]:1). A related demographic explanation is that the arrival of the Brazilian Nagôs’ ancestors in Brazil was indeed concentrated in the 19th century, at the last stage of the slave trade, making them the most recent and therefore least acculturated of major African ethnic groups in Brazil. They also immigrated in huge numbers. However, studies of other African-American cultures have indicated the disproportionate influence not of the last-arriving immigrant groups but of the earliest-arriving ones (e.g., Mintz and Price 1992[1976]:48–50; Creel 1987; G. Hall 1995[1992]; Aguirre Beltrán 1989a, 1989b). Moreover, the long-developing preeminence of Yorùbá/Nagô divinities in the Center-South (Rio and São Paulo [see map A]) did not depend on Nagô numerical dominance there.9 Though the Nagô nation is the most prestigious and imitated in the Center-South, its African ancestors had never predominated among the Africans enslaved there. Likewise, Dahomean divinities and terms prevail in Haitian religion despite the fact that Dahomeans were always a minority among Haitian slaves. Thus, students of the diaspora disagree sharply over the causal relationship between numerical population and cultural predominance among African-American groups.10

Even where the Nagôs did predominate numerically, being the most common has never guaranteed that a particular subculture would become as prestigious as has Nagô religion. In fact, being “common” is precisely what excludes many practices from the canon of elite culture in societies all around the globe.

Other demographic factors might have contributed to the success of Nagô religion in Bahia. In 19th-century Bahia the Nagôs were disproportionately represented among urban slaves and among negros de ganho—that is, the slaves who freely moved about contracting work for themselves in order, then, to supply their masters with some agreed-upon portion of their income. Their freedom of movement also allowed a certain freedom to organize themselves and to commemorate their ancestral practices beyond the supervision of their masters.11 It should be noted, however, that these explanations appear to contradict the overall pattern of explanation dominant in the pan-American literature. The Brazilian Nagô case defies the usual Afro-Americanist view that rural isolation and poverty are the normal conditions for the “retention” of African culture.12

Such contradictions may have contributed to the endurance of Rodrigues’s evolutionary explanation. Rodrigues’s sense that social and biological “evolution” had made the pre–slave trade Nagôs superior and thereby allowed their Brazilian descendants to preserve and diffuse their religion and identity was credible to generations of ethnographers in Rodrigues’s train, including...