![]()

Part One

Theoretical Foundations

![]()

Two

Power and the Varieties of Order

The order created by the United States in the decades after World War II is a curious amalgam of logics, institutions, roles, and relationships. It is an order that has been given various names—the free world, the American system, the West, the Atlantic world, Pax Democratica, Pax Americana, the Philadelphian system. It took shape in the early decades of the Cold War, organized in part as an alliance aimed at countering and containing Soviet power. The United States quickly became a pole or organizing hub within the emerging bipolar global system. American postwar order building was, in this sense, an outgrowth or facet of geopolitical competition and bipolar balancing. Along the way, this American-led order took on hierarchical characteristics. The United States was vastly more powerful than other states within the order. It organized and led the order, underwriting security, stability, and economic openness. A global array of weaker and secondary states became junior partners and client states. But, at the same time, the order was also—at least within its Western core—a community of liberal democracies. These democracies shared a vision of liberal order that predated the Cold War, and they worked together to organize open and loosely rule-based relations that were not simple reflections of power hierarchies. Complex and institutionalized forms of cooperation of increasing depth and breadth marked the order—cooperation that continues today.

How can we make sense of this American-led order? An international order is a political formation in which settled rules and arrangements exist between states to guide their interaction. How can we describe and situate the American postwar order within the wider array of types of international orders? This chapter develops a framework for the theoretical and historical depiction of international orders.

The postwar American-led order plays havoc with prevailing understandings of international relations. The traditional image of world politics is one in which a group of roughly equally capable states—so-called great powers—shape the system as they compete, cooperate, and balance with each other. States operate in a decentralized system where order is established through an equilibrium of power among the major states. The anarchical character of the international system is manifest in the decentralization of power and authority. States are sovereign and formally equal. No state—not even a powerful one—“rules” the global order under conditions of anarchy. The insecurity and competition that flow from this anarchical situation drives state behavior and gives international politics its distinctive and enduring features.

This theoretical perspective, however, has a hard time making sense of the American-led international order. This is true in several respects. First, the relations between states within this order are not based on a balance-of-power logic or even overtly marked by anarchy-driven power politics. Bargains, institutions, and deeply intertwined political and economic relations give the American-led order its shape and character. The extensiveness of interdependence, specialization of functions, and shared governance arrangements are not easily understood in terms of anarchy and power balancing. Second, the end of the Cold War did not return international order to a multipolar great-power system, but rather it led to a unipolar system in which a single state overshadows and dominates the functioning and patterns of global politics. States—both those inside the American-led order and outside—have not responded to unipolarity with clear and determined efforts to balance against the United States. The result has been several decades of world politics marked by the commanding presence of a leading state and the absence of a return to a multipolar balance-of-power system.

In effect, the anarchy problematic misses two features of the American-led international order—hierarchy and democratic community. First, the order does in fact look more like a hierarchy than like an anarchy. In critical respects, the order is organized around superordinate and subordinate relationships. States have differentiated roles and capacities. Several leading states—Japan and Germany—do not possess the full military capacities of traditional great powers. Rules and institutions in the global system provide special roles and responsibilities for a leading state. Although a formal governance structure does not exist, power and authority is informally manifest in hierarchical ways. The United States is situated at the top of the order and other states are organized below it in various ways as allies, partners, and clients. Second, the order is marked by the pervasiveness of liberal relationships. At least in the Western core of this order, other liberal democratic states engage in reciprocal and bargained relations with the United States. The order is organized around an expanding array of rules and institutions that reduce and constrain the prevalence of power politics. The United States shares governance responsibilities with other states. In these various ways, the American-led order has characteristics of a hierarchy with liberal features.

To make sense of the American-led order and the transformations under way, we need to expand our theoretical vision. I do so in several steps. First, I look at the background conditions that shape and limit the ways in which political formations are manifest. Here the focus is on variations and shifts in the distribution of power. I identify various types of power distributions, and I distinguish them from the political rules and relationships that might arise in the context of different arrays of material capabilities among leading states. It is in this context that we can see the ways in which the American postwar order has traveled through the era of Cold War bipolarity into the recent decades of unipolarity.

Second, I look at the three general ways in which international order can be organized. These are orders built on balance, command, and consent. Each of these logics of order is rooted in a rich theoretical tradition. Each tradition offers a sweeping account of the logic and character of international order. Each offers a grand narrative of the rise and transformation of the modern international system. And importantly, each offers a major argument about the way in which stable international order is formed and maintained.

These logics direct attention to the shaping of international order as it occurs at periodic historical turning points, particularly in the aftermath of major wars. Settlements of great-power wars have often turned into ordering moments when the rules and institutions of the international order are on the table for negotiation and change. The principal components of settlements are peace conferences, comprehensive treaties, and postwar agreements on principles of order. These ordering moments not only ratify the outcome of the war. They also lay out common understandings, rules and expectations, and procedures for conflict resolution. As such, these settlements have played a quasi-constitutional function, laying the foundation and enshrining the organizational logic of international order.

Finally, I look more closely at the ways in which these logics of order have been manifest in the American-led postwar order. In particular, I explore the continuum that exists between imperial and liberal forms of hierarchy and rule. This continuum seeks to capture variation in the degree of formal and coercive control by the leading state over the policies of weaker and secondary states. Several aspects of hierarchical order shape the degree to which it takes on liberal characteristics. These include the degree to which the leading state provides and operates within a set of agreed-upon rules and institutions; the degree to which the leading state provides public goods to other states; and the degree to which the leading state provides “voice opportunities” for weaker and secondary states in the order. The American-led order did manifest these liberal features—and its overall logic and character can be described as liberal hegemony.

The Distribution of Power

Relations between states are built on foundations of power. International order has come in many varieties over the centuries, but in each instance it has been shaped and constrained by the distribution of power. Indeed, the first questions we typically ask about international order are about power. How is power distributed? Does one state or a few dominate the system, or is power diffused more broadly? What are the material capabilities that matter in world politics? How do relations between states change as power shifts? In asking these questions, we are making a distinction between the distribution of power and the political formations that are built on top of the distributed capabilities of states. The distribution of power refers to the way in which material assets and capabilities are arrayed among states and other actors. The distribution of power tells us who has power but not how it will be used. The distribution of power provides opportunities and constraints for states within the system. But it does not, in itself, determine the way power is exercised or how order is created.

The international distribution of power can vary widely. Power capabilities can be more or less concentrated in the hands of one, a few, or many states.1 These variations are typically described in terms of polarity. A multipolar system is one in which power is spread out or diffused among several states. In a bipolar system, power is concentrated in the hands of two states. A unipolar system is one in which one state possesses substantially more power capacities than other states. In multipolar and bipolar systems, power capabilities among two or more states are more or less in balance or equilibrium. These multiple “poles” provide competing centers of power, and the character of their cooperation and competition shapes the overall international order. In a unipolar system, power is concentrated and unbalanced—the unipolar state has no peer competitors.2 It alone is a pole of global power.

Realist theory offers the most systematic characterizations of state power and polarity. In the realist rendering, a pole is a state that is powerful by virtue of its aggregation of various material capabilities: wealth, technology, military capacity, and so forth. Kenneth Waltz provides the classic definition of a pole. A state takes on the position of a pole within the larger system if it possesses an unusually large share of resources or capabilities and if it excels in all the various components of state capabilities, including, most importantly, the “size of population and territory, resource endowment, economic capacity, military strength, political stability and competence.”3

This conception of power and polarity has been invoked by scholars who offer general depictions of the global distribution of material capabilities over many centuries. In these accounts, the modern state system has tended to be multipolar from its European beginnings in the seventeenth century into the mid-twentieth century. During these centuries, a small group of major states organized the system and competed for influence and control. After World War II, the era of great-power multipolarity gave way to a bipolar global system dominated by the United States and the Soviet Union. The power structure became unipolar in the 1990s with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the continuing growth of America’s material capabilities relative to the other major states.

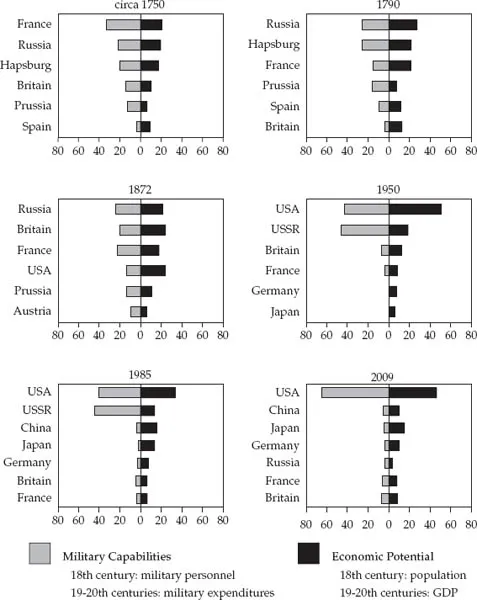

These broad differences in the international distribution of power are captured in aggregate measures that combine economic and military size. These percentage indicators provide measures of both economic capacity and military might. The gross national income (GNI) measure—particularly utilizing measures of both aggregate and per capita GNI—provides the single best measure of power capabilities.4 In contrast, military spending captures effort, not potential.5 The multipolarity of the earlier periods is contrasted with the bipolarity of the Cold War and the unipolarity of the last two decades. (See figure 2-1.)

These measures of aggregate power show the distinctiveness of the postwar era of bipolarity and the last two decades of unipolarity. In previous centuries, power was shared more or less evenly among a group of great powers. Leading states were only slightly set apart from the other great powers. Moreover, in these earlier periods the leading states were either great commercial and naval powers or great military powers on land, but they were never both. Great Britain emerged as the leading economic and naval power in the nineteenth century, but other major states matched or exceeded British capabilities in some areas. As Brooks and Wohlforth observe, “[e]ven at the height of the Pax Britannica, the United Kingdom was outspent, outmanned, and outgunned by both France and Russia.”6 Similarly, the United States emerged from World War II as the world’s leading economy, and it was unrivaled in many areas of military power, including air and naval capabilities. But during the Cold War, the Soviet Union matched the United States in overall military capabilities, reinforced by its vast territorial holdings and military investments. During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union were both poles in a geopolitically divided world.

Figure 2-1: Distribution (Percentage) of Economic and Military Capabilities among the Major Powersa (17th–21st Centuries)

Sources: Eighteenth-century data: Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (New York: Random House, 1987). GDP for 1870–1985: Angus Maddison, Monitoring the World Economy, 1829–1992 (Paris: OECD, 1995); GDP for 2009: sources from Table 1.2; military expenditures for 1872–1985: National Material Capabilities data set v. 3.02 at http://www.correlatesofwar.org. The construction of these data is discussed in J. David Singer, Stuart Bremer, and John Stuckey, “Capability Distribution, Uncertainty, and Major Power War, 1820–1965,” in Bruce Rus...