- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A behind-the-scenes account of the derivatives business at a major investment bank

The financial industry's invention of complex products such as credit default swaps and other derivatives has been widely blamed for triggering the global financial crisis of 2008. In Codes of Finance, Vincent Antonin Lépinay, a former employee of one of the world's leading investment banks, takes readers behind the scenes of the equity derivatives business at the bank before the crisis, providing a detailed firsthand account of the creation, marketing, selling, accounting, and management of these financial instruments—and of how they ultimately created havoc inside and outside the bank.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Codes of Finance by Vincent Antonin Lépinay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Finance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Princeton University PressYear

2011Print ISBN

9780691163956, 9780691151502eBook ISBN

9781400840465PART I

From Models to Books

We start our journey into financial engineering by scrutinizing the product. This close focus has one objective: understanding how the theoretical imaginings of financial engineers become financial services, which are then maintained by traders on actual Exchanges. The development of new products is one of the secret steps of market operations. The genesis of products is protected because that is where the know-how of the engineers shows itself the most clearly. For the bank to survive and attract new clients, new financial services must embody new possibilities for investors and their money. Banks are in a race against other financial service firms, but they are also in a race against themselves: they have to survive the tyranny of the formula they have sold and make sure that when the time comes, they can return the client’s capital and its formula-based performance.

CGPs are synthetic products drawing on existing securities. As compilations of outstanding financial products twisted by the formula, they need to be outfitted with their own models. The appeal of the product— as a combination of insurance and investment—also creates the central puzzle that the trading room wrestles with: finding the model that suits the product. Given that this articulation is the source of major difficulties in the trading room, it is worth clarifying the terms of the product/model dance using an older derivative.

A “call” on a listed stock, traded on an Exchange, is a product designed to meet what are supposed to be needs of a class of clients. The description of a “call” can assume many forms, but when a client wants to buy one, he or she is usually handed a series of documents that contain the following information:

A definition:

A call option is a contract that gives the holder the right (“the option” not the obligation) to buy a certain quantity of an underlying security from the writer of the option, at a specified price (strike price) up to a specified date (expiration date).1

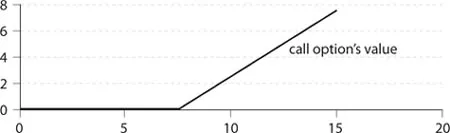

Figure 3. A Call Option’s Value with a Strike Price of 7.7

This graph does not factor in the cost of the option. Should it do so, it would shift the curve downward of the cost of the option itself. The horizontal line across the bottom (the x-axis) represents the underlying instrument’s price. The vertical axis shows the profit/loss as the underlying instruments move up or down. The heavy line is our payoff.

A formula of its payoff:

Call option payoff = Max (0, [Underlying price – Strike price]).

With the definition and the formula, a visual representation of the call’s value is also usually offered [see figure 3].

The simplicity of its payoff is disarming: one underlying and a linear deduction of the call’s value. This instrument derives its value from a mechanical relation between a price, defined by the contracting parties, and a fluctuating price, beyond the parties’ control. Nothing else interferes in the value of the call: the whole economy could go wild, but as long as the underlying exhibits a price, the call has a value. When the term of the product has come due, the owner of such a contract can say how much money it is worth and replace the value with the price by replacing “(Underlying price – Strike price)” by its amount. Now, clients who purchase such contracts may have good reasons to sell them before they mature. As a treasurer, you may discover that the company on which you held a call option is no longer among your priorities. You had simplistically imagined that it was a direct competitor of yours and that any market share it would acquire would be a negative against you. Holding call options automatically allowed you to benefit from its stock performance so that you would balance the loss of market shares by a financial gain. You realize other factors weigh on the competition, and the mechanical relation between your business performance and competitors’ stock performance does not hold true. It is time to get rid of a useless insurance. But how much should it be worth? The current difference (Underlying price – Strike price) may be positive on one day, but who guarantees it will still be so in the next few days? The one certainty offered by the product comes from its term. Then, and only then, assessing the value of the contract requires nothing but good reading skills so as to compare the current price and the strike price.2 Before that final moment, however, the value of the contract is much trickier to discover, and that is when models are taken out of the drawer and applied to the contract to figure out its value; that is, how much money another person who needs such a service should pay for it.

Derivatives offer contrasting qualities: they are literal but engineered—some would say tortured. The range of their prices is fully covered by their literal formula, so that once I have the statistical qualities of its underlyings (price and volatility, or higher order variations of prices to some of its parameters) one cannot know additional factors of future price changes. Yet, they are also engineered into sometimes long and tortured formulas in such a way as to make their value difficult to anticipate for a client. Obviously, a possibly infinite number of factors will influence the ups and downs of the underlying but once captured, the value of the derivative is given by the formula’s mechanical relation to the underlying.

The engineered component, coupled with their novelty, explain why it is difficult for clients to deal with the uncertainty of these products’ value by resorting to “inner experience.” The engineering of derivatives challenges even chief financial officers (CFOs), who swim daily in the sea of big figures—thousands and millions of Euros. Even products as plain as calls contain numbers with clauses and conditions that make difficult the calculation of their value. The innovative engineering offered by the bank makes all forms of personal expertise by the client irrelevant, as finance becomes nothing but numbers folded in so many ways as to render calculation a distant dream.

One could suspect that more competition will help solve the dilemma of traders and clients from the indeterminacy of engineered derivatives’ value before their term comes. In what sounds like good economic reasoning, let the market do what it does best and produce information; let thousands of other interested traders do the work of valuation. Yet, even if a client was ready to use an existing market to let competition point to the efficient price, he or she could not find the perfect determination of value because the constant innovations outpace the production of a market where competition could take place.

Those studying the series of problems that derivatives created have been quick to equate these features—literal but engineered into opaque products—with fraud. The contention points to the asymmetry of information: designers engineer products in such a way as to protect their expertise against clients’ clear and informed assessment; they sell fancy formulas, but they are mostly smoke and mirrors and marketing ploys, at best. At worst, derivatives are fraudulent. In this book, I do not aim to settle this long-held question. Rather, I document how financial engineering and its tortured formulas burden the operators and disrupt the conduct of operations in the bank. One of the consequences of these products’ indeterminacy is the need to have a sense of the value of the financial product through models. Sometimes, these models are publicly available and anyone interested in the price of these transactions can use them.

A Model

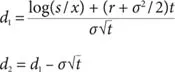

Models are central to assessing financial derivatives’ value because these products are fully synthetic: their value can be captured through an equation that feeds on a few variables from the underlyings that can easily be extracted from the market.3 One famous model for such simple products as the call, bought in order to hedge businesses with foreign partners is the Black–Scholes pricing formula. Its equation is as follows:

c = sΦ(d1) – xe−rtΦ(d2),

where

Log denotes the natural logarithm, and

c = the value of the call option

s = the price of the underlying stock

x = the strike price

r = the continuously compounded and risk-free interest rate

t = the time in years until the expiration of the option

σ = the implied volatility for the underlying stock

Φ = the standard normal cumulative distribution function.4

Even readers with a taste for mathematics or physics formalisms will pause temporarily to decipher the terms of the equation and its components. At first sight, one does not recognize the simple terms of the call behind the equation. What occurred between the literal expression of a product and its particular expression in formal terms is the science and art of modeling. When the product disappears behind its model, what is left of its relevant features? The Black–Scholes model works by leaving the literal terms of the product’s payoff (Max [0, . . . ]) only to capture its possible value over a wide range of underlying price variations. During this apparent digression and roundabout route, sight of the product is lost, and risks are taken as quantitative engineers test the market to assess the quality of their model. If the model simplifies the product, despite the more intimidating equation, the operators working in the trading room also expect the new model expressions of their risky contracts to be sharper. If the product comes under the guise of a model and is filtered by a model, and if it is novel enough to challenge existing models—which would make its price common knowledge and its issuance tied to very low commercial margins—and if in addition it needs to renew itself on a regular basis to dodge competition, then the question becomes: How do engineers know when a model is good, when a product is risky, and when they are maintaining it properly?

The constant mandate to innovate or perish creates a quasi-experimental environment within the bank, with experts bringing to the room a variety of approaches and different timings of interventions. The quasi-experiment is polarized by two modes of knowledge production: the secluded5 exploration of models by the bank researchers and the practical exploration of products by traders when they attend to their portfolios. The practical exploration engaged by traders addresses these financial products fully dressed—decked out with all of their technological apparatus. They do have their say in the choice of these launches, but their intimate, daily experience of the markets does not take precedence over the engineers’ more theoretical elaborations. Traders’ complex experience, rarely put into words or made explicit, positions them differently from the bank’s more confined researchers. During the course of their market explorations, traders regularly discover new properties of the products they manage. These products return information about the markets in which they are launched as well as about their design.6 Variations in prices of products offer some indications concerning a segment of their market, and the multiple cross-checks carried out by traders on their products may coax the market to reveal relationships that were not necessarily anticipated.7

This exercise in the extraction of the properties of financial products under real-world circumstances becomes even more central when the trading room innovates aggressively and its operators are faced with unknown products. They learn about them as they test them under a variety of conditions. Some tests are simulations and attempt to re-create the market environment in a computer; some others are carried out in the market itself. But this exploration of commercial products is not that of mathematics or physics. Here, properties are more akin to weather system anticipation, with goals set to the short to medium terms. Engineers and traders know that understanding and controlling the future payoffs of CGPs is more than brandishing the law of supply and demand, since translating new designs into such notions remains unkown. And when knowledge is forthcoming, it never holds true for long. These dynamics make fruitful the conversation between confined researchers and those active on the markets: traders, and, to a lesser extent, salespeople, communicate things to the engineers, which the latter cannot anticipate or imagine. Traders preceded engineers in the financial markets. They developed skills through contact with transactions and they formulated ad-hoc theories of how markets worked. Confined researchers appeared only later, bringing with them the legitimacy earned in fields connected to finance (physics, mathematics, and accounting). This crossover was not an obvious one, and the rules of these other disciplines did not always satisfy the needs of the type of experimentation required by finance.

CHAPTER 1

Thinking Financially and Exploring the Code

The trading room is a place where new financial products are created, sold, and maintained. This process might seem simple, at least in its fundamentals. It involves the purchase and sale of new and traditional products with the aim of guaranteeing the greatest income for the bank while minimizing the risk of losses. It turns out, however, that having even an approximate idea of the value of some of these products is not at all intuitive. Such is the payoff and risk of financial innovations. Typically, clients and competitors do not know how to assess these products and find themselves having to rely on the initial inventor. These are simply the dynamics of product innovation: new products create temporary rents for the innovator. Yet, this very inventor is also frequently working in the dark, searching for the value of his or her creations. As a consequence of this uncertainty, the trading room is also a place where models are developed to figure out the value of these inventions. In this chapter,1 I document and analyze the imperatives and the uncertainty that innovative structured financial products create for the grammar and lexicon of the “penser financierement” (thinking financially), the motto among engineers and traders. By its composition, the trading room is heterogeneous, with several bodies of experts claiming to “think financially.” The languages that are adopted for thinking through and communicating new products reflects this discontinuity. This chapter documents a series of such languages. The chronology of their presentation does not itself reflect either ontological preeminence or the order of emergence. Nevertheless, it is not an arbitrary order. After a clarification of the trading room motto and the two primary approaches to financial engineering that were at play at General Bank, the chapter starts from the least stabilized forms of codifications, with operators figuring out the reactions to products by hand. Escalating from hands-on to program-based, codes gain resistance and become full-fledged characters of the financial conversation in the room.

Penser Financierement

“Thinking financially” was a recurring theme in the trading room.2 Operators would rank each other along the line of this gradient: whatever one’s training, one was assessed on one’s ability to think more or less financially. Yet, no one could articulate clearly what this mode of thinking entailed; it lent itself to at least two interpretations. The most mundane of these sees finance as a domain to which “thinking” must apply. Finance is seen as a set of products, rules, and institutions different from competing sets of other rules and goods, such as those that govern cultural goods, for example. In other words, people in finance must reckon with financial objects and treat them on their own terms. This first reading of the trading-room motto isolates the thinking from its domain of application. A second, more challenging interpretation of the motto, sees thinking as being subverted by the objects it embraces: thinking is not a faculty independent of and anterior to the financial domain under consideration. On the contrary, it is a mode of thinking writ large, a total cognitive style necessary to capture financial activities and products. Thinking this way requires not a cold head and a quiet room but rather is contaminated by the objects of investigation themselves. Grasping these innovations entails letting their form of existence seep into the operator, whether an engineer or a trader. This second understanding of the penser financierement motto established a much higher bar for operators, as they had to first discover and then learn a style. And the discovery component was to be collective. Complicating the attempt to penetrate new products and weigh their specific risk, operators from different disciplinary backgrounds were at work simultaneously: mathematicians and physicists, computer scientists and salespeople, traders and lawyers. Each discipline had a claim on the proper way of speaking about financial products and on the way that would minimize the risks taken by issuing them en masse. The variety of expertise brought together from the first moment of innovations to the end of the deal and the settlement of the payoff forced operators to master idioms that were often foreign to their educational backgrounds.

At stake in the imperative of thinking financially is the nontrivial p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface Financial Innovation from within the Bank

- Prologue A Day in a Trader’s Life

- Introduction Questioning Finance

- Part I From Models to Books

- Part II Topography of a Secret Experiment

- Part III Porous Banking: Clients and Investors

- Conclusion What Good Are Derivatives?

- Appendix A Capital Guarantee Product: The Full Prospectus

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index