![]()

CHAPTER 1

Academic Science as an Economic Engine

ON 4 OCTOBER 1961, the president of the University of Illinois received a letter from Illinois governor Otto Kerner. In the letter, Governor Kerner asked the flagship institution to study the impact of universities on economic growth, with an eye toward “insur[ing] that Illinois secures a favorable percentage of the highly desirable growth industries that will lead the economy of the future.”1

In response, the university convened a committee that met for the next eighteen months to discuss the subject. But despite the university’s top-ten departments in industrially relevant fields like chemistry, physics, and various kinds of engineering, the committee was somewhat baffled by its mission.2 How, it asked, could the university contribute to economic growth? Illinois faculty could act as consultants to companies, as they had done for decades. The university could provide additional training for industrial scientists and engineers. Scholars could undertake research on the economy. But, the committee’s final report insisted, “certain basic factors are far more important in attracting industry and in plant location decisions, and therefore in stimulating regional economic growth, than the advantages offered by universities.”3 In 1963, the University of Illinois—like almost every university in the United States—had no way of thinking systematically about its role in the economy.

In 1999, thirty-six years later, the university faced a similar request. The Illinois Board of Higher Education declared that its number-one goal was to “help Illinois business and industry sustain strong economic growth.”4 This time, though, the university knew how to respond. It quickly created a Vice President for Economic Development and Corporate Relations and a Board of Trustees Committee on Economic Development.5 It titled its annual State of the University report “The University of Illinois: Engine of Economic Development.”6 It expanded its program for patenting and licensing faculty inventions, launched Illinois VENTURES to provide services to startup companies based on university technologies, and substantially enlarged its research parks in Chicago and Urbana-Champaign.7 It planned to pour tens of millions of dollars into a Post-Genomics Institute and tens more into the National Center for Supercomputing Applications.8

What changed during this period that caused the university to react so differently to similar situations? That question is the puzzle driving this book. It has become common knowledge, at least on university campuses, that academic science is much more closely linked with the market today than it was a few decades ago. In the United States, a university research dollar is now twice as likely to come from industry as it was in the early 1970s, and industry funding has increased ninefold in real terms since then.9 The patenting of university inventions, a practice that was once rare and sometimes banned, has become routine. About 3,000 U.S. patents are issued to universities each year—eight times the number in 1980 and more than thirty times that in the 1960s—and universities now bring in more than $2 billion in licensing revenue annually.10 In some fields, it has become common for faculty to also be entrepreneurs; in others, it is a lack of consulting ties that is now looked on askance.11 Universities once self-consciously held themselves apart from the economic world. How and why did they begin to integrate themselves into it?

This book attempts to answer these questions. The conventional wisdom about why universities become more involved in the marketplace emphasizes two factors. First, the move is seen as the predictable result of universities’ ongoing search for new resources. After two decades of rapid growth in government funding for academic science, budgets stopped increasing in the late 1960s and stagnated through most of the 1970s.12 When this happened, universities, which had grown accustomed to constant expansion, turned to the market as a way of acquiring additional resources. A second argument focuses on the role of industry in pulling universities toward the market. During the 1970s, many cash-strapped firms cut back on doing research—particularly basic research?themselves.13 Industry, it is presumed, looked to universities to replace the basic research it was no longer conducting internally.

I argue that while there are elements of truth to these explanations, the main reason academic science moved toward the market was not a search for new resources or the changing needs of industry. Instead, I make two central claims about why universities’ behavior changed. The first is that it was government that encouraged universities to treat academic science as an economically valuable product—though not by reducing resources so that universities were forced to try to make money off their research. The second is that the spread of a new idea, that scientific and technological innovation serve as engines of economic growth, was critical to this process, transforming first the policy arena and eventually universities’ own understanding of their mission.

Despite the perception that universities were secluded ivory towers in the 1950s and 1960s, even this period saw regular experiments with practices that tied science to the marketplace, including the creation of research parks, industrial affiliates programs, and industrial extension offices. But in these decades, there were many barriers—financial, legal, and normative—to the spread of such activities. This situation persisted through the mid -1970s. In the late 1970s, however, policy decisions began to change universities’ environment in ways that removed many of these barriers and in some cases replaced them with incentives. The result was the rapid growth of activities like patenting, entrepreneurship, and research collaboration with industry, which by the mid-1980s were becoming widespread in academic science.

These government decisions were made because policymakers became enamored with the idea that technological innovation helps drive the economy. Though the idea itself was not new, historically it had had little political impact. But by the late 1970s, the conjunction of a growing body of economic research, the concerns of industry, and a favorable political situation led to its embrace. For years, the United States had faced an extended period of economic stagnation, including high unemployment, high inflation, low productivity growth, and an energy crisis. Policymakers, desperate for a way out, began arguing that this was, at least in part, an innovation problem, and that policies that explicitly connected science and technology with the economy could help close a growing “innovation gap” with countries like Japan. This led to a variety of policy decisions meant to strengthen innovation as a means of achieving economic goals. These decisions came from diverse locations and reflected a whole spectrum of political and economic philosophies. Many of them were not even aimed at universities. Collectively, however, they changed the environment of academic science in a way that stimulated and legitimized the spread of market-focused activities within it.

This policy-driven change in universities’ resource and regulatory environment was critical in encouraging their turn toward the market. But the idea behind the decisions mattered, too, as universities, perceiving the political success of arguments about the economic impact of innovation, began to seize upon this new way of thinking about science. Universities had always been more open to taking an active economic role than the ivory-tower stereotype would imply. But, as the University of Illinois example suggests, before the 1970s universities had a different way of thinking about their impact on the economic world. They saw universities as providing the fundamental science that firms would draw upon as needed to solve industrial problems and make technical advances. That is, universities saw academic science primarily as an economic resource.

By the early 1980s, though, universities were starting to follow policymakers’ lead in seeing science as more than just a resource. Increasingly, universities also saw science as having the potential to actively drive economic growth by serving as a fount of innovation that could launch new industries or transform old ones beyond recognition. Science, universities came to believe, could actually serve as an economic engine.

The shift from a “science-as-resource” to “science-as-engine” model had a major impact on the university. It changed the calculus through which universities made decisions about what kinds of activities were appropriate to pursue. It gave universities a new mission: to facilitate economic growth by making sure their research reached the marketplace. It encouraged universities to move away from a passive role in which they simply created the knowledge that industry would draw on—or not—as needed. Instead, they would start working actively to turn scientific innovation into economic activity through technology transfer, faculty entrepreneurship, spinoff firms, and research partnerships with industry. The assimilation of new ideas about the impact of innovation on the economy led logically enough to other new ideas about what the relationship between academic science and the commercial world should be, and the changed environment policymakers had created made such ideas easier to put into practice. By the time the University of Illinois was asked again how it could help the state’s economic growth, it had both a new way of thinking about the question and the surroundings that made it possible to turn those thoughts into action.

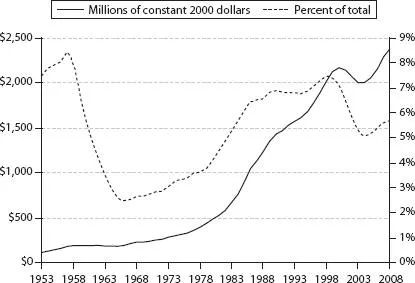

Figure 1.1. University R&D spending provided by industry, 1953–2008 (in millions of constant 2000 dollars and as a percentage of total spending). Adapted from NSB (2010:appendix table 4–3).

THE CHANGING NATURE OF ACADEMIC SCIENCE

No single indicator can capture all the ways the relationship between academic science and the market has changed over the decades. But one number at least captures some part of these changes, and helps to highlight when they were taking place: the proportion of academic research and development (R&D) funded by industry, which has risen and fallen over time. Always a small fraction of the total, this number nevertheless tripled between its historical low in 1966 and its 1999 peak (see figure 1.1). (Since then it has declined significantly, a trend returned to in chapter 8.) The total amount of industry funding increased even more dramatically during that period, by an order of magnitude in real terms.

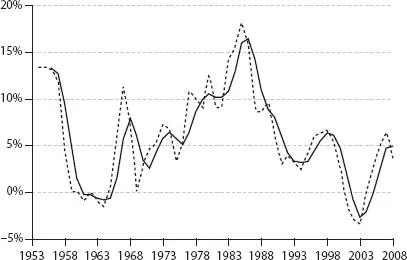

Figure 1.2. University R&D spending provided by industry, percent real change from previous year, 1954–2008. (Dashed line represents annual data; heavy line is three-year moving average.) Adapted from NSB (2010:appendix table 4-3).

The pace of this change shows when the move toward the market was at its fastest. Industry funding plummeted as a percentage of total academic R&D spending in the 1950s and early 1960s as the result of a sevenfold increase (in real terms) in federal funding, even though industry support for university research actually rose during this period.14 But the fraction of funding coming from industry started to increase steadily again during the late 1960s as federal support leveled off. Starting around 1977, increases in industry funding accelerated, and real growth averaged more than 12% a year for the following decade. Between 1985 and 1986, industry funding grew by 18% in inflation-adjusted dollars, the largest jump on record; after that, funding continued to climb but at sharply decelerating rates (see figure 1.2).15

Other, more qualitative measures capture some of the flavor of this shift. For example, university attitudes toward patenting evolved dramatically during this time period. Traditionally, universities rarely patented faculty inventions. Most universities felt that since faculty were already being paid to do research, they didn’t need additional incentives to invent. And patenting was widely seen as incompatible with the scientific ideals of open communication, disinterestedness, and service of the public good. When Jonas Salk, bacteriology professor at the University of Pittsburgh, invented the vaccine for polio, Edward R. Murrow asked him who owned the patent. Salk replied, famously, “Well, the people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”16

The idea that patents were at odds with the nature of science as well as the public interest can be found in many university patent policies of the 1950s and 1960s.17 By no means were all universities categorically opposed to patenting. But many emphasized the university’s aversion to financially benefiting from faculty research, and limited patenting to cases in which it was necessary to prevent a private party from appropriating an invention.18 Johns Hopkins’ policy summed up this attitude: “The ownership and administration of patents by the University is believed undesirable…. Consistent with its general policy, the University makes no claim to royalties growing out of University research.”19

But over time, universities’ perspective on patenting changed. Patenting and licensing are now almost universally encouraged, and seen as a key mechanism through which scientific advances reach the public. Today, more than 150 U.S. universities have technology transfer offices, or TTOs, employing some 2,000 people and filing well over 10,000 new patent applications a year.20 A statement by the Council on Governmental Relations, an association of research universities, reflects this new understanding:

The ability to retain title to and license their inventions has been a healthy incentive for universities…. It is important to recognize that without such incentives, many inventions may not get carried through the necessary steps and a commercial opportunity will be wasted. This wasting of ideas is a drain on the economy, irrespective of whether it was public or private funding which led to the initial invention.21

As the Association of University Technology Managers emphasizes, “These activities can be pursued without disrupting the core values of publication and sharing of information, research results, materials, and know-how.”22

This change in belief may have aligned with what universities saw as their financial self-interest, but that makes it no less sincere. It goes hand in hand with the idea of science as an economic engine, a source of innovation that can create new products, firms, or even industries. From this point of view, the market is the best way of getting university breakthroughs into the hands of the public, and patents create the incentive that makes this happen. As a university administrator interviewed by Leland Glenna and his colleagues stated, “The truth of the matter is that if things get created at the university and they never get pushed out into the industry sector and turned into a product, they really don’t benefit the public good other than for the knowledge of their having existed.”23

As the university itself has come to focus on the commercial impact of science, so have individual scientists. In the 1950s, academic scientists were supposed to be indifferent to worldly goods. As Steven Shapin has pointed out, in 1953 a letter-writer to Science was able to argue that the American scientist

is not properly concerned with hours of work, wages, fame or fortune. For him an adequate salary is one that provides decent living without frills or furbelows. No true scientist wants more, for possessions distract him from doing his beloved work. He is content with an Austin instead of a Packard; with a table model TV set instead of a console; with factory-rather than tailor-made suits, with dollar rather than hand-painted neckties, etc., etc. To boil it down, he is primarily interested in what he can do for science, not in what science can do for him.24

While it seems certain that such asceticism was never completely the norm, the fact that such a claim could even be seriously made suggests that a change in ideals has taken place. Ever since Genentech’s 1980 initial public offering (IPO) made University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) biochemist Herbert Boyer worth $65 million overnight, the possibility of owning the Packard—or a garage full of them—has not been lost on ambitious scientists.25 Academic scientists still hold a range of attitudes toward the appropriate role of commercial activity in the university. But a large number join the belief that science has value because it expands human knowledge with the belief that the market is key to maximizing the impact of that knowledge—and that financial rewards are completely appropriate for those who facilitate that process.26 As one entrepreneurial academic has said, “If there is some gold in the hills, and you happen to get a chunk, well, there is no point in leaving it in the ground if somebody is going to pay you for it.”27

All these changes have been a part of a gradual shift in values and beliefs, not a wholesale transformation. But they have led to tensions within the university about its proper role in society and where, or if, a boundary between university and industry should be drawn. Critics of this move toward the market see it as posing a threat to science in service of goals that should be secondary, at least for univer...