![]()

PART ONE

DEVELOPMENT AND ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE

![]()

TWO

THREE PATHS TO DEVELOPMENT,

THREE RESPONSES TO GLOBALIZATION

Those who know only one country, know no country.

(Lipset 1996, 17)

ECONOMIC development engenders a massive amount of organizational change, but different kinds of it take place under different development circumstances. This chapter characterizes three ideal-typical paths to development and three corresponding responses to globalization. It thus prepares the ground for subsequent chapters to analyze from a comparative institutional perspective the extent to which business groups, small and medium enterprises, foreign multinationals, labor unions, and specific sectors of economic activity have changed and succeeded in the global economy. The economic histories of Argentina, South Korea, and Spain since 1950 provide archetypical illustrations of each of the three paths to development and of the circumstances leading to them.

Globalization and Paths to Economic Development

Over the last half-century countries have variously adhered to the policies proposed by modernization, dependency, world-system, late-industrialization, and neoclassical theories of development. Policy choices have been shaped by a complex combination of causes or constraints, including natural endowments, international pressures and opportunities, and domestic sociopolitical patterns (Haggard 1990). Before venturing into the vexing question of why Argentina, South Korea, and Spain made specific policy choices, however, it is useful to establish the fundamental ways in which the policies themselves vary from one another.

The literature on political economy has typically characterized different approaches and paths to development by means of pairs of opposed policies, such as export-led growth versus import-substitution, modernizing versus populist, nationalist versus pragmatic, or protectionist versus liberal (Maravall 1993; Haggard 1990; Gereffi 1990a; Gilpin 1987). While the specific features of the theoretical models and typologies in the literature differ from one another, they all underline the importance of understanding the extent to which policies create linkages or relationships to the global economy in terms of foreign trade, investment, aid, and debt (Gereffi 1989).

Development Paths in a Context of Globalization

This book’s analysis of organizational change in newly industrialized countries follows an ideal-typical characterization of paths to economic development based on the economic relationships between each country and the global economy. In particular, foreign trade and foreign direct investment tend to have a momentous impact on organizational change and on the types of organizations that predominate over time in a country undergoing development and integration with the global economy. While foreign aid and debt are also important in many historical instances (Gereffi 1989), they can be seen as substitutes for foreign direct investment.

Previous research on the political economy of development suggests that it is crucial to distinguish between outward and inward foreign trade and investment flows because they need not be correlated with each other (Haggard 1990). In fact, one of the prerogatives of the modern state—that institution so intimately linked to development efforts—is precisely to establish the extent to which the domestic economy is exposed to imports and inward foreign investment, and the degree to which exports and outward investment are important to its economic development effort. Decisions about levels of foreign trade and investment are directly related to the “rules of the game” that states are supposed to establish as they implement their development strategy: definitions of property rights, governance structures, and rules of exchange among economic actors, both domestic and foreign (Fligstein 1996). Modernization, dependency, world-system, late-industrialization, and neoclassical theories of development propose policies that result in different configurations of inward and outward flows of foreign trade and investment.

For a given country, outward flows—exports and investment by nationals in foreign countries—will remain at a low level if the emphasis is placed on inward-looking development and on devoting all resources to local investment. The political economy literature has referred to policies that keep outward flows at low levels as the “populist” solution to development, one promoting short-term compromise and income redistribution among interest groups. By contrast, outward flows will reach higher levels when policies encourage firms to sell and, eventually, invest abroad. Such policies may be labeled as “modernizing” (Bresser Pereira 1993; Dornbusch and Edwards 1991; Kaufman and Stallings 1991; Mouzelis 1988).

A similar logic can be applied to inward flows. Imports and investment by foreigners in the country will remain at a low level if there is protectionism and subsidization of domestic firms (trade) or if there is a preference for national private and state ownership of the productive assets in the country (foreign investment). It should be noted that imports and inward foreign investment can be restricted to low levels while firms in the country obtain capital and technology at arm’s length via foreign debt (or aid) and licensing, respectively (Gereffi 1989). Inward flows will reach higher levels as imports and investment by foreign firms are allowed into the country. The political economy literature has referred to policies restricting inward relationships to low levels as “nationalist,” and those allowing for high levels as “pragmatic” or “liberal” (Gilpin 1987, 31–34, 180–83, 274–90; Maravall 1993).

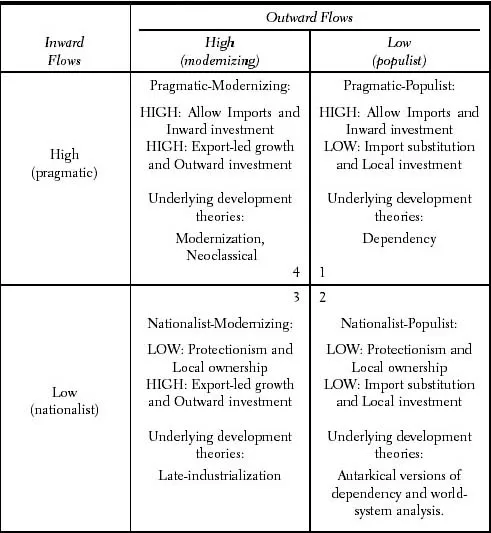

Inward and outward flows appear cross-classified in table 2.1. The low-low configuration follows from a “nationalist-populist” approach. This is a situation in which most developing countries found themselves at midcentury (Haggard 1990; MacIntyre 1994; Maravall 1993). Only extremely autarkical versions of dependency theory and world-system analysis would recommend that countries indefinitely pursue this approach (see Ragin and Chirot 1984, 292–94). Economists and social scientists making very different theoretical assumptions remind us that acute balance-of-payments crises and rampant inflation are likely to occur repeatedly when countries persevere in their efforts to maintain low levels of both inward and outward flows (Bruton 1998; Diaz-Alejandro 1965; Dornbusch and Edwards 1991; Kaufman and Stallings 1991; Haggard 1990; Maravall 1993).

One frequent option to surmount such crises is to allow imports and inward investment to increase, that is, to relax nationalist policies without abandoning populism. The shift toward the “pragmatic-populist,” or high-low, configuration can help stabilize the economy and promote growth by attracting foreign investment and imports of essential capital goods until the economy is ready to fully substitute local production for imports. These changes, however, frequently produce economic and political problems if the domestic interests affected by the opening of inward flows mobilize against it, or if multinationals fail to contribute to local development in terms of technology transfers and profit reinvestment. Thus, it is common to observe populist countries oscillating between cells 1 and 2 of table 2.1 as they apply the policy prescriptions of dependency theory. Argentina, Venezuela, Brazil, and India provide examples of this “erratic” populist path to development (Encarnation 1989; Evans 1979; Haggard 1990; Mouzelis 1988; Tulchin 1993).

The “nationalist-modernizing,” or low-high, configuration in table 2.1 represents the policy prescriptions of late-industrialization theory. It is exemplified in the political economy literature by the so-called developmental or mercantilist states of East Asia (Amsden 1989; Haggard 1990; Johnson 1982; Wade 1990). The state protects domestic firms with policies restricting imports and inward investment, lends money at subsidized rates, and allocates licenses to import technology, machinery, and components to entrepreneurs who commit to increase exports and outward investment in support of such exports. In line with dependency theory, barriers to imports are established to discourage the consumption of consumer goods manufactured abroad. But late-industrialization scholars emphasize the importance of forcing local firms to deliver export growth in return for protection (Amsden 1989). Also at variance with dependency theory, the nationalist-modernizing approach rests on a “‘decoupling’ of foreign capital and foreign technology from foreign direct investment.” The necessary foreign capital and technology are obtained in the forms of loans and licenses, respectively, as opposed to direct investment (Mardon 1990, 119–20). Nationalist-modernizing development may also be denominated “mercantilist export-led” growth.

TABLE 2.1

Ideal-Typical Foreign Trade and Investment Configurations

Finally, the “pragmatic-modernizing” configuration in table 2.1 implies high levels of both imports and exports and of inward and outward investment, and has been recently adopted by emerging economies adjacent to developed areas—Mexico, Ireland, Puerto Rico, or the southern European countries—as well as by the commercial enclaves of Singapore and Hong Kong (Haggard 1990; Maravall 1993). Both modernization and neoclassical theories of development propose pragmatic-modernizing policies that are conducive to high inward and outward flows of foreign trade and investment. In modernization theory, increasing exports are thought to facilitate economic takeoff because trade widens the market and allows for more specialization. Foreign investment, while neither a necessary nor a sufficient precondition for takeoff, is deemed to facilitate development (Kerr et al. [1960] 1964, 92–94; Rostow [1960] 1990, 39, 49). Modernization scholars even argue that “external intrusion by more advanced societies” in the form of imports and foreign investment exposes traditional patterns of behavior and encourages modernization (Rostow [1960] 1990, 6, 31–32). Similarly, neoclassical theories of economic development and reform invariably propose open or liberal foreign trade and investment policies (Balassa et al. 1986; Sachs 1993). Pragmatic-modernizing development can also be labeled “liberal export-led” growth.

Why Argentina, South Korea, and Spain?

This book focuses on the cases of Argentina, South Korea, and Spain because these countries illustrate the three paths to development that can be inferred from the four ideal types in table 2.1. Back in the late 1940s and 1950s, the three countries were pursuing relatively similar import-substitution policies in order to improve their lot as relatively backward developing countries. They became members of the International Monetary Fund during the late 1950s. Their development paths, however, diverged considerably over the following 40 years. Argentina has oscillated between the nationalist-populist and pragmatic-populist orientations, that is, followed an “erratic populist” path. Korea, by contrast, shifted from nationalist-populist to nationalist-modernizing, becoming an export and foreign investment power but without allowing imports or inward investment. Finally, Spain shifted from nationalist-populist to nationalist-modernizing and pragmatic-modernizing.

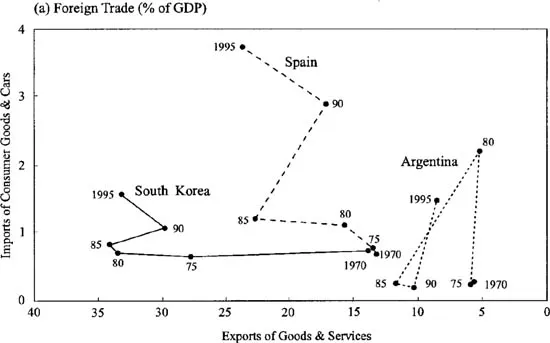

Figure 2.1 presents evidence corroborating these assertions. In the upper panel the levels of imports and exports as a percentage of GDP are plotted for each country and shown for every five years between 1970 and 1995. In the lower panel inflows and outflows of foreign investment are shown. While Argentina has oscillated vertically (i.e., remained fairly populist in orientation), Korea and Spain shifted toward higher levels of exports and outward foreign investment over time. Unlike Korea, Spain has also allowed imports and inward foreign investment to increase rapidly. Thus, the strategy of case selection for intensive comparative study follows the “variation-finding” approach (Skocpol 1984, 368–74; Tilly 1984, 116–24). The three cases will be systematically compared in subsequent chapters to arrive at a “principle of variation” linking development paths to organizational forms.

Figure 2.1. Outward and Inward Foreign Trade and Investment for South Korea, Spain, and Argentina. (International Trade Statistics Yearbook; World Investment Report; World Investment Directory. Dorfman 1983, 426; Katz and Kosacoff 1983, 140).

South Korea and Spain have seen their per capita incomes rise very quickly over the last 40 years, suggesting perhaps that nationalist and pragmatic approaches to development work reasonably well as long as they are combined with outward-oriented growth. Argentina’s erratic populism, by contrast, produced no growth between the mid-1970s and the early 1990s. However, Argentina and its firms are not to be seen as a general failure, for they have succeeded in several respects. The argument in this book is not that some development models work better than others—which is a risky proposition given the continuing turmoil in the global economy—but rather to show that development and globalization produce diversity in economic action and organizational form. Moreover, each approach to globalization and development results in different combinations of strengths and weaknesses, and of successes and failures (see chap. 8).

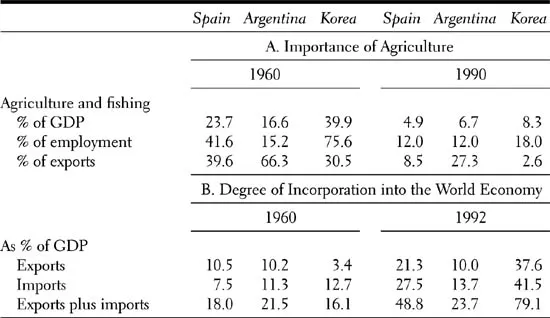

Before describing in detail why each of the three countries followed a different development path, it is important to highlight the key advantages in comparing Argentina, South Korea, and Spain over the 1950–99 period. First, these are three countries of roughly similar size. A country’s size, especially in terms of population, has a major impact on the export-orientation of its firms, the possibilities for import-substitution, and the behavior of foreign multinational enterprises (Haggard 1990, 26). Second, while these three countries’ development paths have diverged considerably over time, they all started in the nationalist-populist configuration back in the 1950s (Amsden 1989; Lewis 1992; Sachs 1993, 22–26). Third, in spite of the obvious differences in natural endowments, the importance of agriculture in each country has dropped considerably over the last four decades (table 2.2, panel A). Fourth, in addition to their increasingly different degrees of incorporation into the global economy (table 2.2, panel B), these three countries barely engage in foreign trade among themselves or invest in each other.1 The lack of significant interconnections between these economies over the last 50 years makes it safe to assume that developments in one country are not affecting those in the other two. Fifth, the distribution of manufacturing activities by industry four decades ago was very similar across the three countries (see table 2.3). Sixth, policymaking in each country was long shaped by authoritarian regimes (like in most other newly industrialized countries), making this book a tale of three generals—Perón, Park, and Franco.2 And perhaps most importantly, previous development approaches have identified these three countries as paradigmatic illustrations of each path. Neoclassical theorists extol the Spanish model (Sachs 1993, 22–26), while late-industrialization proponents sing the praises of South Korean policymaking (Amsden 1989), and Argentine development until the 1990s is presented as a textbook case of populism (Cardoso and Faletto [1973] 1979, 133–38; Mouzelis 1988). It should be carefully noted, however, that during the 1990s Argentina has perhaps applied neoclassical policies most extensively, while the South Korean and Spanish states continued to intervene massively in the economy through industrial and welfare policies, respectively.

TABLE 2.2

Agriculture and Incorporation into the World Economy: Spain, Argentina,

and South Korea, 1960 and 1990s

Sources: World Tables; Yearbook of International Trade Statistics; Banco de Bilbao; Estadísticas de Argentina, 1913–1990; Korea Statistical Yearbook.

For these seven reasons, comparing the impact of the Argentine, South Korean, and Spanish development paths on organizational change is not only intellectually exciting but also appropriate and instructive. After 50 years of development efforts, the three economies contain different types of organizational forms, with distinctively different consequences for the role their firms play in the global economy. In the next sections I set the stage for the analysis of organizational change and economic performance contained in subsequent chapters by reviewing the economic development trajectories of each of the three countries. I systematically compare how natural endowments, international context and policies, and sociopolitical patterns affected development policy choices (see table 2.4).

Argentina: The Paradigm of Erratic Populism

One of the mysteries of the second half of the twentieth century is

how Argentina, so rich in so many ways, has had such difficulty

fulfilling its great potential.

(De la Balze 1995, 1)

TABLE 2....