![]()

CHAPTER 1

Disjointed Pluralism and

Institutional Change

WHATEVER ELSE a national legislature may be, it is a complex of rules, procedures, and specialized internal institutions, such as committees and leadership instruments. Particular configurations of these rules, procedures, committees, and leadership instruments may serve the interests of individual members, parties, pressure groups, sectors of society, or the legislature as a whole. As a result, as any legislature evolves through time, little is more fundamental to its politics than recurrent, often intense, efforts to change its institutions. Congressional politics has depended crucially on such innovations as the “Reed rules” of 1890, the Senate cloture rule adopted in 1917, the creation of congressional budget committees in 1974, the House breakaway from seniority rights to committee chairmanships in 1975, and the package of reforms adopted by Republicans when they took over the House in January 1995.

What explains the politics of institutional change in Congress? How is it that congressional institutions have proven remarkably adaptable to changing environmental conditions and yet a never-ending source of dissatisfaction for members and outside observers? This book addresses these questions. The answers, I argue, can be found in the multiple interests that undergird choices about legislative institutions. Members have numerous goals in mind as they shape congressional rules and procedures, the committee system, and leadership instruments. Entrepreneurs who seek reform can devise proposals that simultaneously tap into an array of distinct member interests. But conflicts among competing interests generate institutions that are rarely optimally tailored to meet any specific goal. As they adopt changes based on untidy compromises among multiple interests, members build institutions that are full of tensions and contradictions.

The claim that members have multiple goals is by no means new. Fenno’s Congressmen in Committees (1973) is but one of several important studies that have explored how members’ electoral, policy, and power goals shape legislative behavior and institutions.1 Nonetheless, an increasingly popular way to think about legislative institutions uses a single collective interest to explain the main features of legislative organization across an extended span of congressional history. Examples of this approach include Cox and McCubbins’s (1993) partisan model of legislative organization, Krehbiel’s (1991) informational theory of committees, and Weingast and Marshall’s (1988) distributive politics model. Each of these theories attempts to show how legislative institutions are tailored to achieve a collective interest shared by members.

While such models have proven valuable in isolating important causal variables and in explaining specific features of legislative politics, focusing on the relationships among multiple interests generates additional insights into congressional organization. This involves much more than the claim that one has to look at everything—all imaginable interests and coalitions—to understand Congress. Instead, I argue that analyzing the interplay among multiple interests produces new generalizations about how congressional institutions develop. Such an analysis can help us understand both the adaptability and the frustrations that characterize congressional organization.

Based on an analysis of important institutional changes adopted in four periods, 1890–1910, 1919–32, 1937–52, and 1970–89, I argue that members’ various interests makes “disjointed pluralism” a central feature of institutional development. By pluralism, I mean that many different coalitions promoting a wide range of collective interests drive processes of change. My analysis demonstrates that more than one interest determines institutional change within each period, that different interests are important in different periods, and, more broadly, that changes in the salient collective interests across time do not follow a simple logical or developmental sequence. Furthermore, no single collective interest is important in all four periods. Models that emphasize a particular interest thus illuminate certain historical eras, but not others.

These pluralistic processes of change do not in themselves require a dramatic revision in how we think about legislative institutions. Even if no model focusing on a single interest can explain everything about congressional institutions, critical insights may well emerge from a series of such models, each explaining a few key components of legislative organization. Eventually, a theory that synthesizes these approaches may be possible, providing a fuller understanding of the dynamics of congressional institutions.2

The qualifier disjointed suggests why that approach is only partly satisfying. By disjointed, I mean that the dynamics of institutional development derive from the interactions and tensions among competing coalitions promoting several different interests. These interactions and tensions are played out when members of Congress adopt a single institutional change, and over time as legislative organization develops through the accumulation of innovations, each sought by a different coalition promoting a different interest.3

This disjointedness calls into question the utility of a series of simple models that each seeks to explain a particular facet of legislative organization, and it also complicates efforts at theoretical synthesis. Models that focus on a single organizational principle, though valuable in many respects, deflect attention from how the relationships among multiple interests drive processes of change. Integrated theories that encompass several interests are potentially helpful but should not assume, as is sometimes apparently their implication, that institutions fit together comfortably to form a coherent whole (see, for example, Shepsle and Weingast 1994). Instead, my case studies suggest that congressional institutions are often ambiguous or contradictory.

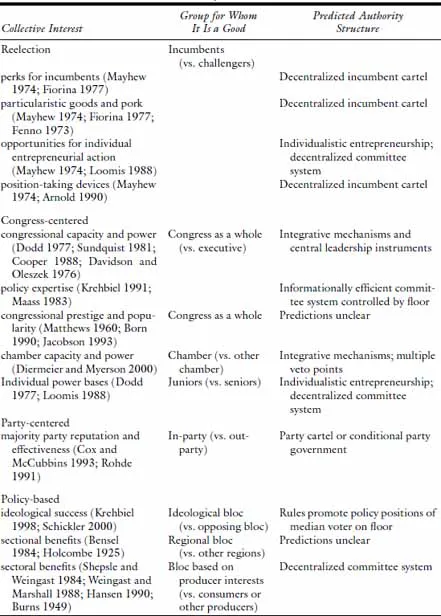

Because the conceptual value of disjointed pluralism hinges on the many collective interests that motivate members, I first review prominent models of collective interests and the expectations that these models generate for institutional development. I then detail the implications of these multiple interests for understanding congressional change. Finally, I summarize the research design and review the findings from each period.

COLLECTIVE INTERESTS

Five distinct and partially contradictory kinds of collective interest could motivate the design of legislative institutions (see table 1.1). The first is rooted most directly in members’ reelection interest, which potentially unites incumbents behind devices that increase their electoral security. The second consists of broad, institutional interests that also may unite all members: bolstering the capacity, power, and prestige of their chamber or of Congress as a whole. By contrast, the other interests are likely to divide members into competing groups. The third, members’ interest in access to institutional power bases, can generate conflict between those who currently have disproportionate access and those who lack access. Similarly, the fourth, members’ party-based interests, pits majority party members against members of the minority. Finally, the fifth, policy-based interests, is rooted in the connection between institutions and policy outcomes. Institutions may favor certain policies at the expense of others; as a result, ideological, sectional, and sectoral divisions over policy may spill over into conflicts about institutional design.4

In his classic study, Congress: The Electoral Connection (1974), David Mayhew argues that virtually every facet of congressional organization can be understood in terms of members’ shared reelection goal. As Mayhew and others point out, a variety of institutional arrangements promote reelection, including staffing and franking privileges (Mayhew 1974; Fiorina 1977); credit-claiming opportunities gained most often through pork-barrel, distributive policies (Mayhew 1974; Fenno 1973); opportunities for individual entrepreneurial activity (Loomis 1988); devices to avoid taking positions on difficult issues (Arnold 1990); and platforms for position taking on popular issues (Mayhew 1974). More generally, reelection-based models typically predict that Congress will have a decentralized committee system that spreads influence widely, thereby providing members with numerous opportunities to cultivate constituent support (Mayhew 1974; Fiorina 1977).

TABLE 1.1 Summary of Collective Interests

On observing the many incumbent-protection devices embedded in congressional institutions, Mayhew (1974, 81–82) suggests that “if a group of planners sat down and tried to design a pair of American national assemblies with the goal of serving members’ electoral needs year in and year out, they would be hard pressed to improve on what exists.” This raises the question: why do we need to go beyond members’ shared stake in reelection to understand congressional development? Why is the reelection interest, on its own, not sufficient? Part of the answer to this challenge is empirical: in the chapters that follow, I provide considerable evidence that other interests shaped important changes in congressional organization. But there are also strong theoretical grounds for the importance of multiple interests.

Notice first that the same member careerism that makes reelection a powerful influence on congressional organization has the potential to make other interests salient as well. The value of reelection hinges in part on Congress’s status as a powerful and prestigious institution.5 Maintaining congressional power is not something that members can simply take for granted. Indeed, the twentieth century has witnessed the decline of numerous elected legislatures (Huntington 1965). The most prominent threat to congressional power has been the rise of the modern presidency and the surrounding executive establishment. Therefore, one can expect careerist members to act in concert to defend congressional power, particularly following major episodes of executive aggrandizement. Examples include the committee consolidation brought about by the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946 (Cooper 1988; Dodd 1977) and the more centralized budget process provided by the Budget Act of 1974 in the wake of the battle over impoundments with President Richard Nixon (Sundquist 1981).6

A focus on congressional capacity and power can lead to two somewhat different expectations about congressional organization.7 Dodd (1977) and Sundquist (1981) argue that centralized leadership—typically in the hands of party leaders—is necessary for Congress to formulate coherent, broad-reaching policies and therefore to compete effectively with the executive branch. In their view, a fragmented, committee-dominated system has been the main source of congressional weakness. Sundquist in particular praises the 1974 Budget Act as an example of a centralizing change intended to safeguard congressional power.

In contrast to Dodd’s and Sundquist’s emphasis on centralization, Krehbiel’s (1991) informational model suggests that a strong committee system facilitates congressional policymaking, provided that the committees are supervised by floor majorities.8 Krehbiel argues that committees are not autonomous entities but agents of the floor, supplying information that reduces legislators’ uncertainty about the consequences of proposed bills. The floor creates committees that are representative of its own policy preferences, because representative committees are most likely to specialize and to transmit their information to the rest of the chamber (Krehbiel 1991). All members benefit from such a committee system, which boosts congressional capacity and power.9

Viewing Krehbiel in the context of Dodd and Sundquist reveals a tension: The need for specialized policy expertise leads to strong committees, but using this information in a coherent manner requires coordinating the activities of these committees. Whereas Dodd and Sundquist believe strong party leaders are essential for this coordination, Krehbiel’s model suggests that floor majorities rein in and channel committee activities. Notwithstanding these differences, both Dodd and Sundquist and Krehbiel argue that members have an incentive to design institutions that promote congressional policymaking capacity.

While Congress-centered interests have led to several major reforms, members have at times defined institutional power more narrowly, in terms of their chamber rather than Congress as a whole. Interchamber rivalry has received little attention from congressional scholars, but Diermeier and Myerson (2000) have recently developed a formal model that highlights this dynamic. They conclude that the members of one chamber can increase their collective access to desired resources, such as campaign contributions, by adding more veto points in their chamber. In other words, House members stand to gain a greater share of contributions or other favored resources if lobbyists face more institutional hurdles in the lower chamber than in the Senate. Though none of the cases I examine fit this precise dynamic, there are several examples of institutional changes intended to empower one chamber relative to the other. For example, Joseph Cannon’s (R-Ill.) revitalization of the speakership in the early 1900s derived bipartisan support from representatives’ dissatisfaction with their chamber’s decline relative to the Senate.10

Whereas all members may have a similar commitment to defending congressional power (or at least the power of their chamber), other collective interests divide members into competing groups. As Fenno (1973) and Dodd (1977) have pointed out, one of the reasons that members seek reelection is to exercise power as individuals. This ambition creates the potential for conflict between members with disproportionate access to institutional power bases and those, such as junior backbenchers, who lack such access and therefore share an interest in decentralization (Dodd 1986). Indeed, several instances of institutional reform analyzed in this book derived support from junior members—often drawn from both parties—who advocated a greater dispersion of power bases (see Schickler and Sides 2000). Along these lines, Diermeier’s (1995) model of floor-committee relations suggests that a sudden influx of junior members can undermine existing arrangements, leading to major institutional changes.

Power bases are also particularly salient to careerist members. A member who plans to leave Congress soon is less likely to carve out a niche in the House or Senate than is one who plans to spend many years in Washington. This is not only because power bases can facilitate reelection, but also because careerist members may value power within Congress for its own sake. Therefore, members’ power base goals, like the goal of safeguarding congressional capacity and power, have probably become more potent as careerism has increased.

At the same time, members’ power base goals are often in tension with their interest in congressional capacity and power. Dodd (1977) argues that the drive for individual power leads to a highly fragmented authority structure.11 Members end up placing policymaking responsibility in “a series of discrete and relatively autonomous committees and subcommittees, each having control over the decisions in a specified jurisdictional area” (Dodd 1977, 272). Individual entrepreneurship flourishes because each member can use her committee or subcommittee to initiate new policies or oversight activities. But, as noted above, the difficulty, according to Dodd, is that the resulting fragmentation impedes workable responses to broad policy problems. This, in turn, erodes the influence of the legislative branch as the president and bureaucracy acquire power at the expense of Congress. In the end, members’ pursuit of individual power saps Congress of its power as an institution (Dodd 1977, 1986). This is but one example of important tensions among members’ multiple interests.

Another important cleavage affecting institutional design is party. In Cox and McCubbins’s (1993) formulation, majority party members are united by their stake in the value of their common party label. Party members suffer electorally if voters believe the p...