![]()

PART ONE

The Value of Museums

Encyclopedic museums, like the British Museum, with collections representative of the world’s diverse, artistic production, encourage tolerance and inquiry. They are a legacy of the Enlightenment, and are dedicated to the principle that access to the full diversity of human artistic industry promotes the polymath ideal of discovering and understanding the whole of human knowledge, and improves and advances the condition of our species and the world we inhabit.

Some hold that recent nationalist, retentionist cultural property laws are challenging the very basis of encyclopedic art museums. When the United Nations was founded in 1946, there were fifty-one member nationstates. There are now 191. Most of these have retentionist cultural property laws: either ownership laws, in which antiquities found in the ground within the modern borders of the modern state are declared state property; export laws, in which specific kinds of objects, even if privately owned, cannot be exported from the modern nation-state without official permission; or hybrid laws, such as preemption rights by which the modern nation-state has a certain period of time within which to decide to buy the privately owned object or allow its export. Of these, the majority date since 1947; and of these, most date from 1970.

In addition, new nation-states have recently adopted international conventions, which further constrain the international movement of antiquities by defining them as “cultural property.” Some have argued that in effect, these conventions condone and support the widespread practice of overretention or, even the hoarding of cultural property, and of antiquities as cultural property.

At the same time the practice of partage, by which archaeological finds are shared between the excavating team and the local, host nation, has all but stopped. Most new nation-states require that all archaeological finds remain where they were excavated as the new nation’s “cultural property.” This is in contrast to the practice of the first half of the twentieth-century, which allowed excavating teams to return to their host museums and universities, whether in the United States or Europe, with a share of the finds for further study and research.

The combination of retentionist cultural property laws, international conventions, and the halting of the practice of partage has discouraged the building of encyclopedic collections. This comes at a time when the world is increasingly divided along ideological, political, and cultural lines and thus challenges the very principles on which the encyclopedic museum, as an Enlightenment museum, were founded: that encyclopedic museum collections should be built to broaden and deepen our understanding of the world’s cultures in all their differences, similarities, and interrelatedness.

Neil MacGregor explores the potential for the modern encyclopedic museum to fulfill the ambitions of its Enlightenment foundation: by using its collections to encourage people to rethink conventional hierarchies of power and importance and to challenge people to consider the historical and current realities of the world’s diverse, complicated, and interrelated cultures. Philippe de Montebello argues that museums should acquire antiquities, even and perhaps especially unprovenanced antiquities, for the contributions they can make to the preservation and further study of our common, ancient past. He notes how such antiquities have been important even to archaeological research, leading archaeologists to sites they may otherwise have missed. He also considers the current constraints on museums wishing to acquire antiquities, and distinguishes between the constraints accepted by European museums and those accepted by U.S. museums. And Kwame Anthony Appiah discusses the implications of the current regime of international regulations on our understanding of our cosmopolitan identity of ourselves as human beings rather than as particular, narrowly defined nationals. He also considers the use and abuse of antiquities as cultural property claimed by national governments.

![]()

To Shape the Citizens of “That Great City, the World”

Neil MacGregor

THE BRITISH MUSEUM

THE IDEA OF THE WORLD UNDER ONE ROOF, as in the encyclopedic museum, was one of the great possibilities of the eighteenth century and the great intellectual challenge to people who wanted to think differently about the world. The British Museum was established very specifically for everybody, for the whole world. Its founders had no doubt what its purpose was. It was established on the proposition that through the study of things gathered together from all over the world, truth would emerge. And not one perpetual truth, but truth as a living, changing thing, constantly remade as hierarchies are subverted, new information comes, and new understandings of societies emerge. Such emerging truth, it was believed, would result in greater tolerance of others and of difference itself.

In this view, the British Museum’s collection was a means to knowledge, a path to a better understanding of the world, and a way of creating a new kind of citizen for the world. It is important to insist that the notion of “citizen” in this case was never a national one. The museum was only called the British Museum because it was not the king’s museum; it belonged in a very real sense to the people, to citizens. Sir Hans Sloane—the donor of the museum’s founding collection—first offered his collection to the British government. But he stipulated that if they wouldn’t take it, it was to be offered to the Royal Academies of St. Petersburg, Paris, Berlin, and then Madrid, in that order. Whichever nation was able to meet two conditions—that the collection would always be together for study and that it would always be open, free to anybody to visit—would be able to keep the collection. It so happened that Britain met these conditions and the collection is now in London, but it could just as easily have been in one of the other four great, international cities.

It is true Sloane wanted his collection first in London, but only because at the time London was the most cosmopolitan and biggest city in all of Europe. It was presumed that more—and more different—people could visit it in London than anywhere else. And that was most important to Sloane. He gave his collection for a purpose, more than to a place. The place was important only insofar as it advanced the purpose for which Sloane gathered and gave his collection of wonderful things. He wanted the museum to be where it would best be used by a large number of people, international people as much as possible. For in his mind, Sloane was a citizen not of just one country, but as Diderot says in his notable letter to Hume, a citizen of “that great city, the world.” In the words of the first director, the British Museum was for the use of “learned and studious men [that meant women as well, of course] as well as natives and foreigners.” And if you want a demonstration that this is a preimperial museum, it’s important to point out that in this context, the “natives” in question here were natives of Britain.

It is also important to point out that the duties of the trustees of the museum were to hold its collection in trust for everybody: strangers as well as subjects of the king. It was a universal museum aimed at a universal audience, for the use of the whole world, based on the belief that its diverse collections would let us—its visitors—understand the world now, and not just its history. It is important to insist on this. The aim of the museum was an understanding of the world as it is today. The museum was to be a civic space in which a discussion could take place and in which we could understand a little better the world and our place in it.

Of course, the museum was to have objects of the familiar sort of classical antiquity, but not simply as familiar things—Grand Tour souvenirs—but for the purpose of sorting out the nature of these objects, their value was as evidence. It was important, for example, to discover that the so-called Piranesi Vase was only 20 percent Roman, the rest was entirely eighteenth-century fabrication (fig. 1.1), and that the great Dr. Woodward’s shield (fig. 1.2), thought to have been made by the Romans to celebrate their victory over the Gauls, was in fact made in Renaissance France. These things were in the museum—indeed the very purpose of the collection—as evidence of truth.

Fig. 1.1. The Piranesi Vase, 2nd century AD. Italy. Marble, eighteenth century, incorporating Roman fragments (h. 9 ft.). The British Museum. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Fig. 1.2. Dr. Woodward’s Shield, ca. 1540–50. France. Embossed iron (d. 14 in). The British Museum, bequeathed by Dr. John Wilkinson, 1818. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The great achievement, I think, of the Enlightenment museum, the encyclopedic museum like the British Museum, was the notion that the context of the museum would allow truths to emerge that could not emerge if the objects were studied only in the context of objects like them; that is, among only objects from the same culture. It was of course important to study Greek and Roman things on their own terms and in terms of Greek and Roman culture, but it was also important to study them in the context of objects from China, for example, where evident, sophisticated notions of moral virtue make it clear that other highly sophisticated cultures were as worthy of study and admiration as the more familiar cultures of Greece and Rome. And not just other ancient cultures, but also newer cultures, like that of Japan. If we want to understand how we think about God and worship, the museum held, we need to think about how the Japanese think about the same.

It was also essential from the beginning that the new, growing world should be part of the changing context of the museum, its collection, and their presentation. The museum had, by 1774, for example, the first Maori object ever seen by Europeans, given to Captain Cook as a charm to bring long life. Such objects were meant to demonstrate again that all societies think and behave, effectively, in the same way. It is this, I think, that is surely the great point of the founding of the British Museum as an encyclopedic museum. Its collections were seen to generate truths that insist on the oneness of the world just as the world itself was beginning to realize that it was irrevocably and irretrievably, interconnected. As Diderot, in his introduction to the seventh volume of the Encyclopédic in the mid-1760s, wrote about the endeavor to gather universal knowledge, it would be so that our fellow men could be brought to love and tolerate one another and recognize the superiority of a universal morality over a particular one.

That’s what the context of the universal museum was meant to do. And the notion of trustees and trusteeship was, I think, central to it. It is worth focusing on this astonishing achievement of English and American law: the notion of trusteeship, quite unknown in continental Europe, that brings with it the notion of an obligation to hold the object for the benefit of others, the whole world, natives as well as foreign, those living now and not yet born. If today we talk about holding these objects in trust for all of humanity, we are using the rhetoric of the eighteenth century. It is an Enlightenment concept and term of law that gives rights to the beneficiaries—the whole world—and gives obligations to the trustees, who work on behalf of the world and its peoples.

What does this mean now? How can we now provide a context for these collections that lets the objects speak about the oneness of the world as we know it today? How can we subvert the habits of thought that keep us from seeing other cultures except in categories of superiority and difference? What of the wonderful hand axes, the butchering tools, discovered by Professor Leakey in the late 1920s in Tanzania in Olduvai Gorge? They are very beautiful things, wonderfully shaped and balanced, like works of art. And by the stratigraphy of the Great Rift Valley where they were found, Leakey was able to establish that they must be at least one-and-a-half to two million years old. This changed our whole understanding of the history of human making. It put the beginnings of that history—of civilization itself—firmly in Africa for the first time and demonstrated very clearly the idea of the oneness of humanity. Over subsequent millennia, objects like these—butchering tools—made their way out of Africa until they allowed our ancestors to butcher better and get that crucial protein advantage over other peoples. This let us conquer the world and build great cities like London, where visitors to the British Museum first saw, were first able to see, the truth of and connection to the origin of their culture, the world’s culture of human making. This evidence thus revealed that humanity is one, that it all comes from Africa, and that our recent success is dependent on the much earlier successes of our African ancestors.

We in the British Museum have been very eager to lend these objects and objects like them to museums around the world. Earlier this year, they were in San Francisco at the Museum of the African Diaspora as a wonderful demonstration of a different African diaspora. At the moment, they are in Beijing as the starting point of an exhibition devoted to the history of world civilizations. And this illustrates something about the different roles a museum like the British Museum can play in the dialogue between Africa and the world. In the same week as the exhibition opened, the United Nations was debating whether or not to condemn the Sudanese government for genocide in Darfur. This raised a very different kind of issue for our museum. How could we present the larger story of Sudan when the whole world is thinking of only one aspect of that long story: the current political situation? There was huge public interest at the time in finding out more about Sudan, and of course huge interest among the very large Sudanese diaspora in Britain. We worked with the Sudanese diaspora groups to insure that large numbers of them could visit from outside London. And we organized debates, public debates, around key objects from Sudan in the British Museum’s collection that put the events of Darfur and the issues confronting Sudan today into a different and wider context.

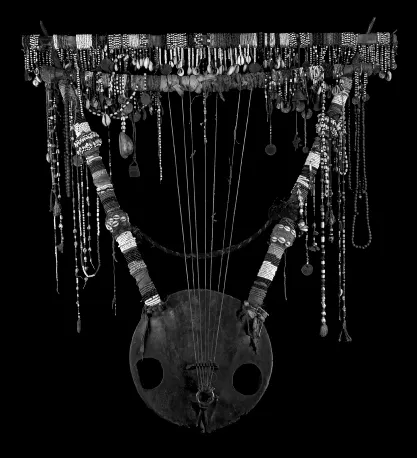

Fig. 1.3. Lyre, late 19th century. Sudan. Wood, skin, glass beads, shells, coins, gut, and iron (h. 39 3/4 in., w. 37 2/5 in., d. 7 4/5 in.). Donated to the British Museum in 1917 by Dr. Southgate. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

At the center of one of the debates organized by the Guardian newspaper was this astonishing object (fig. 1.3). It is a lyre that was once used in ceremonies to banish depression and evil spirits and restore the listener, the patient, to full mental health. It was in such a ceremony that David played his harp before Saul to banish his dark spirits: a tradition that goes unbroken to Mesopotamia of the third millennium BC and thus links the culture of Sudan to the ancient cultures with which, perhaps, our regular, modern visitors were more familiar. In Sudan, this lyre, or harp, gathered around 1900, shows an extraordinary phenomenon: it was made just north of Khartoum and what you see along the top bars are the thanks offerings, the gifts of the people who in the modern era used this essentially pagan, long pre-Christian, long pre-Islamic device of music to charm the evil spirits, and decorated their modern version of it with modern gifts: traditional African talismans, Koranic texts as amulets, rosaries, coinage from Egypt and Yemen as well as from Indonesia, and a large number of ha’pennies with Queen Victoria on them. What this object says is that in Sudan, at a particular moment, all these different communities—Christian, Islamic, traditional religious communities—from Sudan as well as from abroad once lived together in harmony and in peace, and in the modern era drew still upon practices and devices of ancient times. The debate among the Sudanese at our exhibition was whether a device like this—this emblem from their past—could still be meaningful for the Sudanese today? Could it actually represent the Sudan we and they would want to see in the future? This is one of the roles objects play in museums: they offer ways of changing the debate about the contemporary world through old, even ancient, objects, often seen in unexpected juxtaposition.

In the British Museum there is this terrifying head of Augustus (fig. 1.4); a slightly over life-sized head of the emperor, which was originally put up on the southern frontier of Roman Egypt to mark Roman dominion over the edge of the empire. We w...