![]()

Chapter 1

GOD, BLOOD, AND THE TEMPLE

Jesus and Paul on Sin

“The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand. Repent, and trust in the good news!” Thus the first words of Jesus’ mission according to the Gospel of Mark (1.15). But Mark frames Jesus’ proclamation by opening his story with another charismatic figure, John the “Baptizer,” whom he introduces some ten verses earlier. John also called out for repentance, Mark states there. But his mission had been coupled with immersion in the Jordan “for the forgiveness of sins,” and the people who streamed out to John “confessed” their sins as he submerged them (1.4–5). Jesus’ immersion by John—a tradition securely attested in the gospel material—implies that he approved of and consented to John’s message and that his own mission in some sense was a continuation of John’s.1

“Baptism” for the remission of sin would go on to have a long future as a sacrament of the church. That later institution casts a giant shadow backward, obscuring what Mark tells us in the opening verses of his gospel. Jesus’ unadorned statement quite simply defies any idea of a long future. In announcing the imminent arrival of God’s kingdom, Jesus announced as well the impending foreclosure of normal history: “kingdom of God” is an apocalyptic concept. The Baptizer’s call to penitent sinners seems likewise to have been motivated by his own apocalyptic convictions. “Repent, because the kingdom of heaven is at hand,” Matthew’s John teaches (3.2). And the Baptizer warns of looming final judgment by God’s coming agent: “His winnowing fork is in his hand . . . he will gather his wheat into the granary, but will burn the chaff with unquenchable fire” (Mt 3.12//Lk 3.17). Finally, John’s specific combination of repentance plus immersion conjures other religious convictions lost to the later church but vitally significant to early first-century Jews: the importance of purity rituals such as immersion in the process of repentance, which in turn entailed both the temple in Jerusalem as God’s designated place of atonement and the role of offering sacrifices in making atonement.2

Time’s end; repentance before the imminent final judgment; purity; cult; the temple: these are some of the cultural building blocks by which John the Baptizer and Jesus of Nazareth would have constructed their ideas about sin and repentance. But the gospels complicate our view of them on this issue in part because all four evangelists wrote their works sometime after—indeed, perhaps in light of—the first Jewish revolt against Rome. Recounting traditions about the life, mission, and message of Jesus, the gospels relate a narrative context that corresponds roughly to the first third of the first century, from the final years of Herod the Great (d. 4 BCE) to Pontius Pilate’s term of office (26–36 CE). The gospel writers’ own historical context, however—the final third of the first century—runs from the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE to about the year 100. Between these two periods stands a traumatic rupture in Israel’s traditional worship. The evangelists know what the historical John and Jesus did not know: Jerusalem’s temple was no more.3

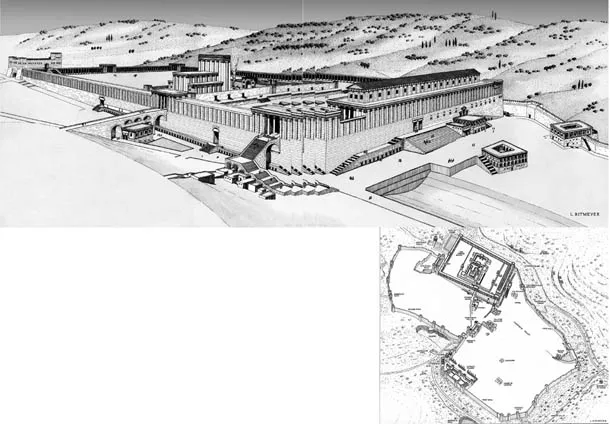

Figure 1. The Second Temple in the early Roman Empire: Jerusalem, Herod’s Temple Mount, reconstruction based on archaeological and historical evidence. “Go, show yourself to the priest, and offer for your purification what Moses commanded” (Mk 1.44). The Temple in Jerusalem—to which Mark’s Jesus directs the cleansed leper—was the premier site for Israel’s offerings. These could be brought for many reasons: to give thanks; to mark the fulfillment of a vow; for purification, or for sin; or (especially on Yom Kippur) to make atonement. By Jesus’ lifetime, thanks to the building and beautification program of Herod the Great (d. 4 BCE), the temple reached the acme of its size and splendor: the wall surrounding its largest courtyard, the Court of the Gentiles, ran almost nine-tenths of a mile. When Paul, in his letter to the community at Rome, praises God for the privileges that he has bestowed upon Israel, the apostle singles out the temple’s sanctuary as the dwelling place of God’s “glory” (doxa in Paul’s Greek, resting on the Hebrew kavod), and as the place of his sacrificial cult (Greek latreia; Rom 9.4). This drawing presents a view of the Herodian Temple Mount from the southwest. Note the size of the human figures, which give a sense of its scale. Courtesy Leen Ritmeyer.

Both the synoptic (“seen-together”) gospels—Mark, Matthew, and Luke—and the Gospel of John project knowledge of the temple’s future destruction back into the lifetime of Jesus. They interpret the death of Jesus in light of the “death” of the temple, and the “death” of the temple in light of the death of Jesus. Mark, for instance, presents Jesus as hostile to the temple. In a scene traditionally described as a “cleansing,” Jesus disrupts the temple’s functioning (an act that leads directly to his own death; Mk 11.15–18) and predicts its destruction: “As he came out of the Temple, . . . Jesus said, ‘There will not be left here one stone upon another that will not be thrown down’ ” (Mk 13.1–2; Mt 24.2 and Lk 21.6 follow suit). The themes of destroying and rebuilding the temple and of the death and resurrection of Jesus appear intertwined throughout Mark’s passion narrative. The Fourth Evangelist, more forthrightly, combines Jesus’ disrupting the temple and predicting its coming destruction into a single prophecy that actually encodes Jesus’ death and resurrection: “But [Jesus] spoke of the temple of his body. When therefore he was raised from the dead, his disciples remembered that he had said this” (Jn 2.21–22). And in an even more daring conflation of Jesus and the temple, the evangelist presents Jesus himself as a sin sacrifice: “Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!” (Jn 1.29).4

The gospels, in brief, offer both a barrier and a bridge to reconstructing the historical Jesus. Their theological commitments and the certain historical knowledge of their authors—the knowledge that God’s kingdom did not arrive in Jesus’ lifetime, that the temple no longer functioned, and thus that their own generation no longer offered sacrifices—contour their portraits and affect them profoundly. Yet the gospels nevertheless remain our best source of information for Jesus’ life, mission, and message. Can we compensate, then, for the ways that the evangelists “updated” their various portraits to the period post-70 CE? Can we somehow historically recontextualize their traditions in order to interpret them within the pre-Christian period of Jesus’ own lifetime? And if we do so, can we come to a clearer understanding of Jesus’ own convictions about sin?

Here the letters of Paul can help. At first blush this may not seem obvious. After all, Paul, like the evangelists, stands at several removes from the historical Jesus of Nazareth. Jesus would have taught in Aramaic, a linguistic cousin of Hebrew; Paul, like the evangelists, thought and taught in Greek, relying on a Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures, the Septuagint, to do so. The evangelists had no direct knowledge of Jesus, nor did Paul, as he forthrightly states (see 1 Cor 15.3). Finally, for Paul as for the evangelists, a significant shift had occurred between Jesus’ audience and their own. Jesus had taught within the overwhelmingly Jewish context of the Galilee and Judea, and most specifically in Jerusalem. His audience was largely fellow Aramaic-speaking Jews. Paul, by contrast, taught within the cities of the western Greek-speaking Diaspora, the most likely setting of the evangelists, too; and his audience was predominantly (if not exclusively) gentile. While the narrative setting of the gospels precludes their depicting Jesus as engaged in a mission to gentiles, they variously present him as anticipating such a mission; and gentiles most likely numbered among the gospel communities, too. Finally, the conviction that Jesus had been raised from the dead charges everything that Paul taught. In all these ways and for all these reasons, Paul, like the evangelists, is also a “Christian” and not a “pre-Christian” writer.5

Yet Paul lived a full generation before the earliest gospel writer, Mark. His letters cluster at mid-first century, a fact that unites him to the historical Jesus and to the original disciples despite all the differences standing between them. Put otherwise, like Jesus of Nazareth and the original disciples, and unlike the evangelists, Paul had no knowledge of the temple’s destruction. In his references to the temple, then, we may be able to catch glimpses of the ways that other early followers of Jesus—and thus, perhaps, even Jesus himself—might have thought and taught about it. Indeed, as we will shortly see, the temple and its cult remained for Paul two of the abiding privileges that God had conferred upon his people (Rm 9.4–5).6

Paul’s letters further preserve another significant datum connecting Jesus’ original disciples, and thus Jesus himself, in a positive way to the temple. According to Paul’s letter to the Galatians, the early movement gave up its Galilean roots and instead, after the crucifixion, settled permanently in Jerusalem (e.g., Gal 1.18, 2.1). Why? Luke/Acts states what Paul’s report implies: Jesus’ disciples continued to worship in the temple (Lk 24.53; Acts 2.46). Jesus’ supposed hostility toward the temple, developed in the later gospels, accordingly seems generated less from a genuine memory preserved about Jesus and more from the evangelists’ own need to explain why God had allowed his temple to be destroyed. (Answer: Jesus himself had condemned the temple. Or, the temple authorities, in condemning Jesus, in turn caused God to condemn the temple. Or, Jerusalem, by not acknowledging Jesus, had sealed its own doom.) But if the historical Jesus had indeed repudiated the temple and its cult, why would his disciples still be worshiping there in the decades after his death? In light of their activity, it seems more likely that no such repudiation had ever occurred. Other traditions preserved within the gospels that suggest Jesus’ piety toward the temple—such as his directive to a cleansed leper to perform there the offerings mandated by Leviticus (Mk 1.40–44 and parr.), or his expectation that his followers would make offerings at its altar (Mt 5.24), or his belief that God dwelled in the temple (Mt 23.21)—accordingly seem more secure.

Yet more than the temple itself held Jesus’ disciples in Jerusalem. If we set their proclamation—that Jesus was raised from the dead and was about to return—against the huge backdrop of biblically shaped apocalyptic traditions, we see as well that they expected Jerusalem—renewed, enlarged, made beautiful—to stand at the center of God’s new kingdom. Already in the classical prophets, Jerusalem had figured prominently as the place where, at the end of days, all humanity would come to worship Israel’s god.

In the days to come, the mountain of the Lord’s house

Will be established as the highest of the mountains,

And shall be raised above the hills.

All the nations shall stream to it.

Many peoples shall come and say,

“Come, let us go up to the mountain of the Lord,

to the house of the god of Jacob; that he may teach us his ways,

and we might walk in his paths.” (Is 2.2–3)

As apocalyptic traditions developed in the late Second Temple period (c. 200 BCE–70 CE), we see the enlargement of these prophetic ideas of restoration and redemption. A battle between the forces of good and evil; the persecution of the righteous, and their ultimate vindication; the ingathering of all Israel; the nations’ repudiation of their idols, and their turning to the god of Israel; the resurrection of the dead and the final judgment; the establishment of universal peace: all of these themes sound in various combinations and in various ways in Jewish apocalyptic traditions, including those later preserved in the Christian New Testament. In the period shortly after Jesus’ death, then, his disciples had their faith in the good news of fast-approaching final redemption reaffirmed by their experience of the risen Christ. They enacted this faith by settling in Jerusalem, the anticipated center of the coming kingdom, living out their commitment to Jesus’ inaugural prophecy: the kingdom of God truly was at hand.7

Jesus’ own apocalyptic commitments set the time frame of his mission to call Israel to repentance; but what was its content? From what to what did he summon his hearers? We can best reconstruct Jesus’ ideas on sin by turning to a core tradition of the covenant, the Ten Commandments. By Jesus’ time, Jews referred to these as “the Two Tables of the Law.” The first five commandments governed relationship with God; the second five, relations between people. When Josephus, the Jewish historian contemporary with the evangelists, characterizes the mission of John the Baptizer, he communicates his message by employing this pious shorthand. “John exhorted the Jews to lead righteous lives,” writes Josephus, “to practice justice [Greek: dikaiosune] toward their fellows and piety [Greek: eusebeia] toward God, and in so doing to join in immersion. . . . The immersion was for the purification of the flesh once the soul had previously been cleansed through right conduct” (Antiquities of the Jews 18.116–19).8

Thus:

First Table: Piety toward God | Second Table: Justice toward Others |

1. Worship no other gods | 6. No murder |

2. No graven images (idols) | 7. No adultery |

3. No abuse of God’s name | 8. No theft |

4. Keep the Sabbath | 9. No lying |

5. Honor parents | 10. No coveting |

According to Josephus, then, the Baptizer’s call to repentance—tshuvah, in the Hebrew of later rabbinic idiom: “turn”—thus meant, precisely, returning to God’s commandments as revealed in the Torah. How radically new was this message? In the Jewish context presupposed by both Josephus and by the evangelists, it wasn’t. And the Baptizer’s emphasis on attending to the inner dimension of repentance (“cleansing the soul through right conduct” in Josephus’ phrasing) before the external protocols of atonement (“purification of the flesh” through immersion) is a stock theme in Jewish penitential tradition of all periods. However, John coupled his call to recommit to the Torah both to bodily purification and to apocalyptic warnings. Those who failed to heed his warning to repent, says the John of Matthew and Luke, will “burn with unquenchable fire”: “Even now the ax is laid to the root of the trees. Every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit”—that is, the fruit of repentance in Matthew 3.8—“is cut down and thrown into the [apocalyptic] fire” (Mt 3.10).9

John’s message apparently had a major impact on Jesus. In all gospel traditions, Jesus begins his own public mission only after his immersion by John. And Jesus too, say the synoptic gospels, oriented his moral teaching by appeal to the Two Tables of the Law. Asked what were the greatest of the commandments, Jesus responds by quoting from the Torah, citing Deuteronomy 6.4 (the first line of the Jewish prayer the Sh’ma) and Leviticus 19.18. “Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one. And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might”—eusebeia, piety toward God (Dt 6.4); and “You shall love your neighbor as yourself”—dikaiosune, justice toward others (Lv 19.18; Mk 12.29–31 and parallels). In Mark’s gospel, Jesus answers a question about inheriting eternal life by responding, “You know the commandments: ‘You shall not murder; You shall not commit adultery; You shall not steal; You shall not bear false witness; You shall not defraud; Honor your father and your mother’ ” (Mk 10.19). Finally, like pious Jewish males then and since, Jesus wore ritual fringes—tzitziot in Hebrew; kraspeda in Greek—whose function was to remind the wearer of God’s commandments (Mk 6.56; cf. Nm 15.37–40, lines also incorporated into the Sh’ma). We can infer from all this that Jesus defined living rightly as living according to the Torah, as summed up in and by the Ten Commandments; that he defined sin as breaking God’s commandments; and that he defined “repentance” as (re)turning to this covenant.

But according to teachings that appear in the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus may have been even stricter about keeping the law than the law itself required. The law said, “Do not kill”; Matthew’s Jesus teaches that anyone who is even angry will be su...