![]()

The Domestic Evolution of the Yijing

PART ONE

What makes a classic? First, the work must focus on matters of great importance, identifying fundamental human problems and providing some sort of guidance for dealing with them. Second, it must address these fundamental issues in “beautiful, moving, and memorable ways,” with “stimulating and inviting images.” Third, it must be complex, nuanced, comprehensive, and profound, requiring careful and repeated study in order to yield its deepest secrets and greatest wisdom. One might add that precisely because of these characteristics, a classic has great staying power across both space and time. By these criteria, and by most other measures as well, the Yijing certainly fits the bill.1

And yet it seems so different from other “classics” that instantly come to mind, whether literary works such as the Odyssey, the Republic, the Divine Comedy, and The Pilgrim’s Progress or sacred scriptures like the Jewish and Christian Bibles, the Qur’an, the Hindu Vedas and the Buddhist sutras. Structurally it lacks any sort of systematic or sustained narrative, and from the standpoint of spirituality, it offers no vision of religious salvation, much less the promise of an afterlife or even the idea of rebirth.

According to Chinese tradition, the Yijing was based on the natural observations of the ancient sages; the cosmic order or Dao that it expressed had no Creator or Supreme Ordainer, much less a host of good and malevolent deities to exert influence in various ways. There is no jealous and angry God in it; no evil presence like Satan; no prophet, sinner, or savior; no story of floods or plagues; no tale of people swallowed up by whales or turned into pillars of salt. The Changes posits neither a purposeful beginning nor an apocalyptic end; and whereas classics such as the Bible and Qur’an insist that humans are answerable not to their own culture but to a being that transcends all culture, the Yijing takes essentially the opposite position. One might add that in the Western tradition, God reveals only what God chooses to reveal, while in traditional China, the “mind of Heaven” was considered ultimately knowable and accessible through the Changes. The “absolute gulf between God and his creatures” in the West had no counterpart in the Chinese tradition.2

Yet despite its brevity, cryptic text, paucity of colorful stories, virtual absence of deities, and lack of a sustained narrative, the Yijing exerted enormous influence in all realms of Chinese culture for well over two thousand years—an influence comparable to the Bible in Judeo-Christian culture, the Qur’an in Islamic culture, the Vedas in Hindu culture, and the sutras in Buddhist culture. What was so appealing about the document, and why was it so influential?

![]()

Genesis of the Changes

CHAPTER 1

We often cannot say exactly when, where, or how ancient texts were born. Some of the reasons are obvious. The further away in time, the more likely a work’s origins will be obscure: memories fade, original materials disappear, alternative versions surface. Often, not least in the case of many of the world’s most sacred texts, diverse materials have accumulated over long periods, edited by different hands under different historical conditions. This is true, to a greater or lesser degree, of the Hebrew Bible (known, with some rearrangement of material, as the Old Testament), the Qur’an, the Hindu Vedas, and the early recorded pronouncements of Siddhartha, the historic Buddha. It is also true of the Zhou Changes, which, when sanctioned as a foundational text by the Chinese state in 136 BCE, became the Classic of Changes, or Yijing.

Myths and Histories

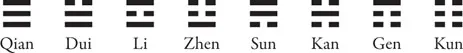

According to a prominent Chinese legend, a great culture hero named Fuxi invented a set of eight three-line symbols known as trigrams, which became the foundation of the Changes. The basic story reads like this:

When in ancient times Lord Baoxi [Fuxi] ruled the world as sovereign, he looked upward and observed the images in heaven and looked downward and observed the models that the earth provided. He observed the patterns on birds and beasts and what things were suitable for the land. Nearby, adopting them from his own person, and afar, adopting them from other things, he thereupon made the eight trigrams in order to become thoroughly conversant with the virtues inherent in the numinous and the bright and to classify the myriad things in terms of their true, innate natures.1

By this account Fuxi was able to represent by means of the eight trigrams a rudimentary but comprehensive understanding of the fundamental order of the universe.

Later, we are told, these eight trigrams came to be doubled, creating a total of sixty-four six-line figures called hexagrams, each with a one-or two-character name that described its fundamental symbolism. Some legends give Fuxi credit for this development; others suggest that another mythological personality, Shennong, may have devised the sixty-four hexagrams. Still other accounts assert that a fully historical figure, King Wen, founder of the Zhou dynasty (ca. 1045–256 BCE), invented the hexagrams and put them in what became their conventional order in 136 BCE. King Wen is also often credited with attaching to each hexagram the short explanatory texts known as judgments, and for adding to each individual line a line statement indicating its symbolic significance within the structure of each hexagram. Some sources claim that King Wen’s son, the Duke of Zhou, added the line statements, and much later Confucius (551–479 BCE) reportedly added the set of commentaries known collectively as the Ten Wings.

One or another version of this general narrative served for more than two thousand years as the commonly accepted explanation for how the Yijing evolved. The archaeological evidence, however, tells a rather different tale.

Trigrams and hexagrams seem to have developed from very early forms of Chinese numerology, including those associated with oracle bone divination—a Shang dynasty (ca. 1600–ca. 1050 BCE) royal practice. By applying intense heat to the dried plastrons of turtles and the scapulae of cattle—a technique sometimes known as pyromancy—the late Shang and early Zhou kings and their priestly diviners were able to produce cracks in the bone, which yielded answers to questions dealing with topics such as family matters, sacrifice, travel, warfare, hunting and fishing, and settlement planning. The “questions” were normally phrased as prayerlike declarations or proposals, the correctness of which could then be tested by divination(s). Written inscriptions carved into a great many of these oracle bones provide direct evidence of the issues the kings addressed as well as the outcomes of their divinations.2

So far archaeological excavations in China have yielded more oracle bones and bronzes with numerical inscriptions that indicate hexagrams than those that indicate trigrams; thus it is at least possible that the latter were derived from the former rather than the reverse, contrary to the common myth. Some scholars have suggested that as early as the twelfth or eleventh century BCE, Shang dynasty diviners may already have begun to analyze trigram and hexagram relationships in terms of techniques previously thought to date only from the final centuries of the Zhou dynasty or later, while others have argued that at least some of the numerical hexagrams found on oracle bones and bronzes are not related to the conventional divinatory traditions of the Changes at all.

Much debate surrounds the issue of when and why various sets of odd and even numbers became “hexagram pictures” with solid and broken lines, and at what point written statements came to be attached to these lines. A good guess is that a more or less complete early version of the basic text of the Changes emerged in China no later than about 800 BCE.3 Recent archaeological discoveries have shown, however, that there were several different traditions of Yijing-related divination in the latter part of the Zhou period, and that hexagram pictures and divinatory procedures took a variety of forms in different localities and at different times.

Some authorities believe that the solid lines of trigrams and hexagrams represent single-segment bamboo sticks used in divination, while broken lines represent double-segmented sticks. Others have suggested an early system of calculation based on knotted cords, in which a big knot signified a solid line and two smaller knots signified a broken line. Still others have argued that the eight trigrams were originally derived either from the cracks in oracle bones or from pictographs of certain key words or concepts that came to be associated with them. Yet another generative possibility may be a rudimentary sexual symbolism. It is difficult even for non-Freudians to look at the first two hexagrams in the received order—Qian and Kun, respectively—and not see representations of a penis and a vulva.

We do not know for certain what the numerically generated trigrams and hexagrams in late Shang and early Zhou oracle bones and other sources might have signified, but by the middle or late Zhou period the primary meanings of the eight trigrams seem to have stabilized (see below). No later than the fourth century, probably earlier, additional meanings began to be attached to these trigrams—meanings that would later become part of an important commentary to the basic text called “Explaining the Trigrams.”

As for the sixty-four hexagrams, we know only that at some point during the early Zhou period—probably about 800 BCE, but perhaps earlier—each of them acquired a name referring to a thing, an activity, a state, a situation, a quality, an emotion, or a relationship; for example, “Well,” “Cauldron,” “Marrying Maid,” “Treading,” “Following,” “Viewing,” “Juvenile Ignorance,” “Peace,” “Obstruction,” “Waiting,” “Contention,” “Ills to be Cured,” “Modesty,” “Elegance,” “Great Strength, “Contentment,” “Inner Trust,” “Joy,” “Closeness,” “Fellowship,” “Reciprocity.”4 There has always been a great deal of debate, however, about the order in which these hexagrams originally appeared, and about the early meanings of the hexagram names and their variants.5

In the conventional version of the Yijing, which may well represent the earliest order of the hexagrams, they are organized into pairs according to one of two principles, each of which involves opposition: The primary organizing principle is one of inversion, by which one hexagram becomes its opposite by virtue of being turned upside down. Fifty-six of the hexagrams fall into this category. The remaining eight, in which inversion would not produce a change, are joined by the principle of lateral linkage—that is, a hexagram structure that would emerge if each line of the original hexagram turned into its opposite.

INVERSION

LATERAL LINKAGE

Most hexagram names in the Changes seem to have been derived from a term or concept that appears in their respective judgments or individual line statements. Take, for example, Gen (number 52 in the conventional order), discussed briefly in the introduction and at greater length below and in subsequent chapters. In this hexagram the character gen appears not only in the judgment but also in all six line statements.6

Here is what one early Zhou dynasty understanding of the judgment and the individual line statements of Gen might have been:

JUDGMENT: If one cleaves the back he will not get hold of the body; if one goes into the courtyard he will not see the person. There will be no misfortune.

First (bottom) line: Cleave the feet. There will be no misfortune. Favorable in a long-range determination.

Second line: Cleave the lower legs, but don’t remove the bone marrow. His heart is not pleased.

Third line: Cleave the waist, rend the spinal meat. It is threatening. Smoke the heart.

Fourth line: Cleave the torso [lit., body]. There will be no mis...