![]()

CHAPTER 1

Location Cubed

THE IMPORTANCE OF NEIGHBORHOODS

Any Realtor can tell you that “the three most important things about real estate are location, location, location.” This oft-repeated refrain, which we might label “L3,” or “location cubed,” underscores the importance of place in human affairs. Everyone needs somewhere to live, of course—a dwelling that confers protection from the elements and a private space for eating, sleeping, and interacting with socially relevant others. Naturally the quality of a dwelling has direct implications for the health, comfort, security, and well-being of the people who inhabit it, and matching the attributes of housing with the needs and resources of families has long been a principal reason for residential mobility in the United States (Rossi 1980). As income and assets rise, households generally seek to improve the housing they inhabit to match it more closely with their changing familial needs, either by moving elsewhere or by investing to modify the current dwelling.

When people purchase or rent a home, however, they not only buy into a particular dwelling and its amenities but also into a surrounding neighborhood and its qualities, for good or for ill. In contemporary urban society, opportunities and resources tend to be distributed unevenly in space, and in the United States spatial inequalities have widened substantially in recent decades (Massey and Fischer 2003; Reardon and Bischoff 2011). Where one lives is probably more important now than ever in determining one’s life chances (Dreier, Mollenkopf, and Swanstrom 2001; de Souza Briggs 2005; Sampson 2012). In selecting a place to live, a family does much more than simply choose a dwelling to inhabit; it also selects a neighborhood to occupy. In doing so, it chooses the crime rate to which it will be exposed; the police and fire protection it will receive; the taxes it will pay; the insurance costs it will incur; the quality of education its children will receive; the peer groups they will experience; the goods, services, and jobs to which the family will have access; and the relative likelihood a household will be able to build wealth through home appreciation; not to mention the status and prestige, or lack thereof, family members will derive from living in the neighborhood.

For these reasons, real estate markets constitute a critical nexus in the American system of stratification (Massey 2008; Sampson 2012). Housing markets are especially important because they distribute much more than housing; they also distribute education, security, health, wealth, employment, social status, and interpersonal connections. If one does not have full access to the housing market, one does not have access to the full range of resources, benefits, and opportunities that American society has to offer (Massey and Denton 1993). Residential mobility has thus always been central to the broader process of social mobility in the United States (Massey and Mullan 1984; Massey and Denton 1985). As individuals and families move up the economic ladder, they translate gains in income and wealth into improved residential circumstances, which puts them in a better position to realize even greater socioeconomic gains in the future. By interspersing residential and socioeconomic mobility, over time and across the generations, families and social groups ratchet themselves upward in the class distribution. In a very real way, therefore, barriers to residential mobility are barriers to social mobility.

Historically, the most important barriers to residential mobility in the United States have been racial in nature (Massey and Denton 1993; Massey, Rothwell, and Domina 2009). Before the civil rights era, African Americans, especially, but also other religious and ethnic minorities, experienced systematic discrimination in real estate and mortgage markets and were excluded from federal lending programs designed to promote home ownership (Jackson 1985; Katznelson 2005). In addition, the practice of redlining, which was institutionalized throughout the lending industry, systematically denied capital to black neighborhoods (Jackson 1985; Squires 1994, 1997). Poor black neighborhoods were often targeted for demolition by urban renewal programs, displacing residents into dense clusters of badly constructed and poorly maintained public housing projects that isolated families by class as well as race (Hirsch 1983; Goldstein and Yancy 1986; Brauman 1987; Massey and Bickford 1992; Massey and Kanaiaupuni 1993; Jones 2004).

The end result was a universally high degree of urban racial segregation in mid-twentieth-century America that only began to abate in the wake of landmark civil rights legislation passed in the 1960s and 1970s (Charles 2003; Massey, Rothwell, and Domina 2009). Progress in eliminating racism from real estate and lending markets was slow and halting, however, and desegregation was only achieved slowly through a multitude of individual efforts undertaken in cooperation with civil rights organizations (Patterson and Silverman 2011). One such effort occurred in the New Jersey suburbs of Philadelphia in 1969, when a group of lower-income, predominantly minority residents joined together to form the Springville Community Action Committee (Haar 1996; Lawrence-Haley 2007). Dismayed at their inability to find decent housing at a price they could afford in their hometown of Mount Laurel, New Jersey, committee members teamed up with a local contractor to build thirty-six units of affordable housing for themselves and other low-income families in the region.

Not surprisingly given the history of race and housing in America, the response from township officials to the proposed development of clustered town houses for low-income minority families was a firm and resounding “no.” The proposed project, they said, would violate Mount Laurel’s zoning policies and land-use regulations, which as in many suburban communities, favored large single-family dwellings set back from the street on large lots (Rose and Rothman 1977). In response, members of the Springville Action Committee joined with local chapters of the NAACP and Camden Regional Legal Services in 1971 to file suit against the township, arguing that its zoning rule effectively prohibited the construction of affordable housing and thus, in de facto if not de jure terms, excluded poor, predominantly minority families from living in the township and enjoying its resources and benefits.

After a prolonged legal battle, the New Jersey Supreme Court in 1975 found for the plaintiffs and handed down a decision that came to be known as Mount Laurel I. In it, the court defined a new “Mount Laurel Doctrine,” which stated unequivocally that municipalities in the state of New Jersey had an “affirmative obligation” to meet their “fair share” of the regional need for low-and moderate-income housing (Kirp, Dwyer, and Rosenthal 1995). The decision and its associated doctrine provided a blueprint for fair-housing advocates and affordable-housing developers elsewhere to launch similar efforts on behalf of low-income residents, and in the ensuing years Mount Laurel I was cited frequently in housing litigation around the country (Burchell 1985; Haar 1996).

Although some community members supported the project from the beginning, such encouragement was not popular. In general, public officials, township inhabitants, and neighbors near the proposed development were none too pleased with the court’s decision and decried it in vitriolic demonstrations, raucous public hearings, and vituperative letters to local newspapers. Ordered to amend its zoning to accommodate its fair-share housing obligations, Mount Laurel Township officials stalled for time and after a year begrudgingly rezoned three unsuitable properties while they appealed the initial court decision.

A second drawn-out court case ensued and in 1983 the Supreme Court reaffirmed its earlier ruling in a decision that came to be known as Mount Laurel II, ordering the township to recalculate its fair share of affordable housing and to redo its zoning amendments quickly. Two years later, Township officials and the plaintiffs reached a settlement that permitted multifamily zoning in the area and provided partial funding to enable the project finally to move forward (Haar 1996). Plans were submitted to local authorities but this action triggered another round of acrimonious public hearings attended by angry citizens who vehemently expressed fears that the development would bring vexing urban problems into their suburban utopia (Kirp, Dwyer, and Rosenthal 1995). Areas of specific concern were the perceived potential for rising taxes, increasing crime, falling property values, and a general disruption of the suburban ethos (Smothers 1997a, 1997b, 1997c).

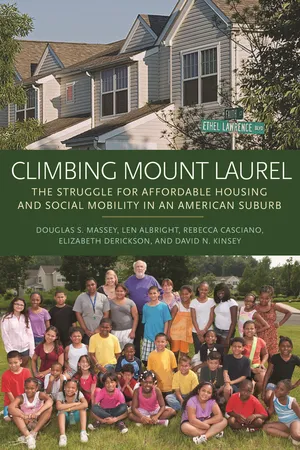

The hearings and public protests dragged on for more than a decade, and it was not until 1997 that the Mount Laurel Planning Board finally approved plans for the project to begin construction. Even then, architectural blueprints had to be finalized, permits solicited, and numerous details negotiated with local officials before the project’s nonprofit developer could break ground. It was not until the year 2000 that the project was finally completed and its developers could accept applications for entry into the project’s one hundred units. Late in the year the first tenants began moving in—thirty-one years after the Springville Community Action Committee originally sought to launch the project, twenty-nine years after the filing of the lawsuit, twenty-five years after Mount Laurel I, and seventeen years after Mount Laurel II. Unfortunately it was also six years after the death of the lead plaintiff, Ethel Lawrence, and the project was duly named in her honor (Lawrence-Halley 2007). In 2004, forty additional units were added to the Ethel Lawrence Homes (ELH) and leased to a new set of tenants, bringing the development to its current size of 140 units.

ELH is unusual in that it is 100 percent affordable. Many affordable housing projects in New Jersey and elsewhere simply require setting aside a percentage of units for low-income families within larger market-rate developments, typically 20 percent. In contrast, ELH from the start was designed and built entirely for low-and moderate-income families. The project presently contains one-, two-, and three-bedroom apartments located within two-story town houses that are affordable to households lying between 10 percent and 80 percent of the regional median income. These criteria yield a remarkably broad range of “affordability,” with units in ELH going to families with incomes that range from $6,200 to $49,500 per year. Given New Jersey’s high-income economy and pricey real estate market, however, no inhabitant of ELH could be considered well-off or affluent, though obviously not everyone is abjectly poor either.

As the project’s first residents moved in, a host of observers looked on with curiosity and no small amount of apprehension. Local officials braced for possible negative reactions from citizens and disruptions arising from the incorporation of poor, minority families into the community’s social fabric. Neighbors, while hoping for the best, nonetheless feared that their premonitions about rising tax rates, declining property values, and increasing crime rates might indeed come true. Fair housing advocates in New Jersey and around the country mostly crossed their fingers and prayed that the disruptions would be few and that the development would enable the new tenants to forge a pathway out of disadvantage. The residents themselves entered with a combination of hope for the future and trepidation about how they would fit into a white suburban environment whose residents had made abundantly clear their skepticism and rancor about the development they were entering.

It is within this contradictory and contentious context that we undertake the present analysis, the first systematic, comprehensive effort to determine as rigorously as possible the degree to which the manifold hopes and fears associated with the Mount Laurel project were realized. In the next chapter we describe in greater detail the Mount Laurel court case and the controversy it generated. We then go on in chapter 3 to describe the construction, organization, and physical appearance of the Ethel Lawrence Homes and to assess the project’s aesthetics relative to other housing in the area. In chapter 4 we outline our study’s design and research methodology, describing the specific data sources we consulted to determine the effects of the project on the community and the multiple surveys and in-depth interviews we conducted to gather information on how the opening of the homes affected residents, neighbors, and the community in general.

Having set the stage in this fashion, we begin our analysis in chapter 5 by evaluating the outcomes that were of such grave concern to local residents and township officials prior to the project’s construction, using publicly available data to determine the effects it had on crime rates, tax burdens, and property values. After detecting no effects of the project on trends in crime, taxes, or home values, either in adjacent neighborhoods or the township generally, in chapter 6 we move on to consider the effects of Ethel Lawrence Homes on the ethos of suburban life. Drawing on a representative survey and selected interviews with neighbors living in surrounding residential areas, we show that despite all the agitation and emotion before the fact, once the project opened, the reaction of neighbors was surprisingly muted, with nearly a third not even realizing that an affordable housing development existed right next door.

In chapter 7 we turn our attention to a special survey we conducted of ELH residents and nonresidents to assess how moving into the project affected the residential environment people experienced on a day-to-day basis. The design of the survey enables us to compare neighborhood conditions experienced by ELH residents both before and after they moved into the project, as well to compare them with a control group of people who had applied to ELH but had not yet been admitted. Both comparisons reveal a dramatic reduction in exposure to neighborhood disorder and violence and a lower frequency of negative life events as a result of the move. Chapter 8 moves on to consider whether the move—and the improved neighborhood conditions it enabled—were sufficient to change the trajectory of people’s lives. Systematic comparisons between project residents and members of the nonresident control group indicated significant improvements in mental health, economic independence, and children’s educational outcomes as a result of moving into the project. In chapter 9 we recap the foregoing results and trace out their implications for public policy and for social theory. We argue that neighborhood circumstances do indeed have profound consequences for individual and family well-being and that housing mobility programs constitute an efficacious way both to reduce poverty and to lower levels of racial and class segregation in metropolitan America.

Before turning to our analyses, however, in the remainder of this chapter we situate the Mount Laurel controversy in a broader theoretical and substantive context. Theoretically, we develop a conceptual understanding of the political economy of place to underscore the distinct character of real estate markets. In doing so, we shed light on the motivations and behaviors of the various participants in the Mount Laurel controversy—project developers, prospective residents, potential neighbors, and local officials, as well as ancillary actors such as housing advocates, civil rights leaders, and suburban politicians. Substantively, we describe the evolving spatial ecology of race and class in the United States, outlining recent trends in racial and economic segregation nationally and in New Jersey, and reviewing the role that housing policies have played in structuring these trends over the past several decades. We also review the evidence adduced to date on the role played by neighborhoods in determining the social and economic welfare of individuals and families.

Although the Mount Laurel controversy was fraught with much anger and animosity, and charged with an abundance of positive and negative emotion, we hope that our theoretical and substantive framing of the issues, along with our empirical analyses of the project and its consequences, will bring needed facts and reason to the debate, enabling citizens to reflect more calmly and policy makers to evaluate more objectively the efficacy of affordable housing developments such as the Ethel Lawrence Homes as social policy. We believe our empirical findings validate the use of affordable housing projects as a tool to address the pressing problems of housing scarcity, poverty alleviation, and residential segregation. We also believe that the study’s methodology and data will be of interest to social scientists, enabling them to assess more definitively than hitherto possible the influence of neighborhood circumstances on individual and family outcomes.

The Political Economy of Place

In a capitalist society such as the United States’, homes are exchanged through markets. Dwellings are offered for sale or rent by owners, landlords, or agents who seek to maximize monetary returns while renters and home buyers seek to obtain highest-quality housing at the lowest possible price. Americans often celebrate “the free market” and denigrate “government interventions” and their correlate “bureaucracy.” But markets are not states of nature. They are social constructions, built and elaborated by human beings for the instrumental purpose of exchanging goods and services (Carruthers and Babb 2000). They do not arise spontaneously and they do not somehow spring into existence in a free and unfettered condition until disturbed by an intrusive state (North 1990; Evans 1995). Instead they are self-consciously constructed by human actors within specific societies and assume a variety of different institutional forms or “architectures,” depending on how they are embedded within surrounding and often preexisting social structures (Hall and Soskice 2001; Fligstein 2001; Guillen 2001; Portes 2010).

In reality, governments create markets and markets cannot exist without government regulation (Massey, Behrman, and Sanchez 2006). Governments create and support a medium of exchange, define property rights, enforce contracts, specify the rights of buyers, delineate the obligations of sellers, and create infrastructures—social, physical, and virtual—to enable market exchanges to occur (Massey 2005a). Many Americans who believe they attained their suburban homes by pulling themselves up by their bootstraps, in fact received significant government help along the way from federally backed loan programs, mortgage interest deductions, subsidies for freeway construction, and other government actions. The issue is not whether governments are involved in markets or not, but whose interests are served by government actions taken to constitute the markets and how these actions influence market performance and the economic outcomes experienced by market participants. These are empirical and not philosophical questions.

For most of human history the things that people needed were exchanged outside of markets, through networks of reciprocal exchange, through inheritance within kinship systems, or by fiat within authoritarian regimes (Massey 2005b). It is only in the past two hundred years that markets have come to dominate human societies; and they did not spring to life fully formed, but emerged gradually over time as economies industrialized, monetized, and expanded to become more fluid, dynamic, and widespread. Compared with markets for goods, commodities, capital, and labor, real estate markets emerged relatively late in the capitalist game because, as we shall see, they are unlike other markets in many ways, making for a unique political economy of place in which the material stakes for market participants are high and emotion plays a salient but often unappreciated role in structuring transactions.

The exchange of homes through real estate markets entails a commodification of place in which market participants seek to maximize the value of property for private use or monetary exchange (Logan and Molotch 1987). A property’s use value is determined by its suitability for carrying out the daily activities of life—eating, sleeping, and interacting with others inside the dwelling while consuming retail, educational, recreational, religious, social, and economic services in the surrounding neighborhood. A property’s exchange value is determined by the amount of money it can command in the short run from rent or sale, or over the lon...