![]()

PART I

WHAT ARE STATISTICAL RACES?

![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

THERE WAS A RACIAL CLASSIFICATION SCHEME IN AMERICA’S FIRST CENSUS (1790), as there was in the next twenty-two censuses, which brings us to the present. Though the classification was altered in response to the political and intellectual fashions of the day, the underlying definition of America’s racial hierarchy never escaped its origins in the eighteenth-century. Even the enormous changing of the racial landscape in the civil rights era failed to challenge a dysfunctional classification, though it did bend it to new purposes. Nor has the demographic upheaval of our present time led to much fresh thinking about how to measure America. It is, finally, time to escape that past. Twenty-first-century statistics should not be governed by race thinking that is two and a half centuries out of date. They poorly serve the nation, especially how it understands and manages the color line and the nativity line—what separates us as races and what separates us as native born and foreign born.

WHAT ARE STATISTICAL RACES?

On April 1, 2010, the American population numbered more than 308 million. When the Census Bureau finished with its decade population count it hurried to inform the president and the Congress how many of those 308 million Americans resided in each of our fifty states. The nation requires this basic fact to reapportion congressional seats and electoral college votes, allowing America’s representative democracy to work according to its constitutional design (see chapter 2).

Immediately after this most basic population fact was announced, the Census Bureau told us how many of the 308 million Americans belonged to one of these five races: White, African American, American Indian, Asian, Native Hawaiian. The bureau reported that a few million Americans belonged to not just one of these five but to two or more. Simultaneously, the bureau reported how many Americans were Hispanics—which, the government insists, is not a race at all but an ethnic group. Incidentally, not all Hispanics got that message, because about half of them filled in a census line allowing Americans to say they belonged to “some other race.” Hispanics, however, are not a race. Hispanics are expected to be Hispanics and also to self-identify as one or more of the five major race groups listed above (this is explained in chapter 6).

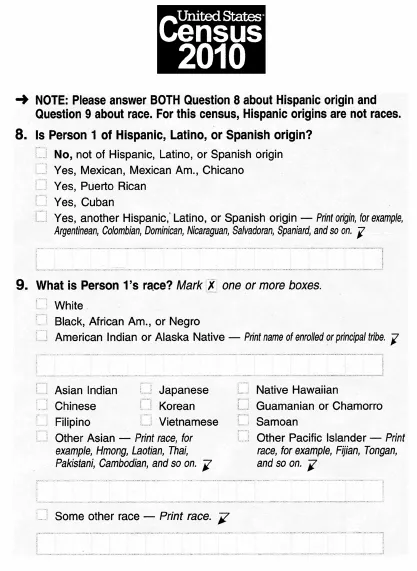

What perhaps puzzles the reader is why race statistics are so terribly important that they are publicly announced simultaneously with the population figures mandated for reapportionment. You may also be puzzled that the census form (fig. 1) dedicates so much of its space to the race and Hispanic question but has no space for education, health, employment, or marital status questions. Are such matters less important than the country’s racial profile? We will examine such puzzles. It is important that we do so because the race and Hispanic questions used in the census have a very long reach. A version of these questions is used in hundreds of government surveys—federal, state, and local—and in official administrative record keeping that captures traits of Americans from the moment of birth to their death: vital statistics, military records, and education and health data. Further, because the statistics resulting from a voracious appetite for information in our modern nation-state are embedded in law, regulations, and policies, there are thousands of private-sector institutions—universities, hospitals, corporations, voluntary organizations—doing business with the government that collect matching race statistics.

America has statistical races. What they are, how we got them, how we use them, and whether today we want or need them are questions that shape this book. America’s statistical races are not accidents of history. They have been deliberately constructed and reconstructed by the government. They are tools of government, with political purposes and policy consequences—more so even than the biological races of the nineteenth century or the socially constructed races from twentieth-century anthropology or what are termed identity races in our current times. Whether these biological, socially constructed, or identity races are “real” is a serious matter, but they are of interest in this book only as they condition what the government defines as our statistical races.

Figure 1. Ethnic and racial categories on the 2010 census form.

What, specifically, are statistical races? Organized counting of any kind—and certainly a census is organized counting—requires counters to know what they are counting, which in turn depends on a classification scheme. Statistical races are by-products of the categories used in the government’s racial classification. And what do the actual 2010 census categories produce? Though you cannot easily tell by looking at the census form, the categories are designed to produce two statistical ethnicities and five statistical races. The ethnicities are Hispanic and Non Hispanic, though this is not evident from a question in which the term ethnicity does not appear. The five statistical races are White, Black, American Indian, Asian, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, which we will learn in chapter 2 directly derive from a color-based division of the world’s population by eighteenth-century natural scientists—white, black, red, yellow, and brown. With these basics established, the census form then unleashes the combinations that result from the “mark one or more” instruction. We will see later how these many combinations have not, as yet, been used to make public policy. They became part of the census to fulfill expressive demands for recognition. Then there is whatever appears on the “some other” line, though again these counts do not become statistical races. So, whatever you think might be going on in these census questions, the political and policy intent is to count the Hispanics separately from everyone else, and to then sort every American, including Hispanics, into five primary races. When I use the term statistical races, it refers to these five groups plus the Hispanic ethnicity.

If you are now confused, you are on your way to understanding why I’ve written this book. That statistical races are real there is no doubt. Law courts, legislatures, executive agencies, media, election campaigns, advocacy groups, corporate planners, university admission offices, hospitals, employment agencies, and others endlessly talk about “how many” African Americans, Asians, Pacific Islanders, American Indians, Whites, and Hispanics there are—and how fast their numbers are growing, how many have jobs, graduate from high school, are in prison, serve in the military, are obese or smoke, own their homes, or marry each other.

If the statistical races are real and important, why does the census form fail to make that clear? In fact, if you take a closer look at the questions you will be even more confused. You should be perplexed that one census-designated race—White—is simply a color. Nothing else is said. The next race is a color, Black (and Negro, which is another way to say Black), but also a descent group—that is, Americans whose ancestors are from the African continent—and in some respects an “ethnicity” as well. Today’s immigrants from Ghana or Ethiopia also go into that category. Then color drops out of the picture altogether. A civil status enters. American Indians/Alaska Natives belong to a race by virtue of tribal membership, which has a clear definition in American law; they can also belong to that race by declaring membership in a principal tribe, which is not a legal status but a self-identification. Look at the census question again. With Whites, Blacks, and Native Americans now listed, there follows a long list of nationality groups. If we read the question stem literally, each of these is a race. The Chinese, the Koreans, the Samoans are presented as if they are independent races. We are not, however, supposed to understand the question literally, but to understand that we become part of the Asian race or the Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander race by checking a national origin or writing one in. Oddly, however, the term Asian only incidentally appears in the question, defining persons from India in a way that doesn’t confuse them with American Indians, and inviting write-in responses, where the examples listed are again nationality groups.

With this nationality nomenclature in mind you might look back at the question on Hispanic/Latino/Spanish origin (terms used interchangeably), where you will see that it is similarly constructed. There is no box indicating Hispanic, but several boxes labeled with nationalities and a write-in space again guided by nationality examples. In a nation famous for its ethnic diversity, you might now be asking, is the census telling us that there are only two ethnic groups that matter (Hispanic and non-Hispanic) while ignoring all white European national origin groups (Swedes, Germans, Italians, Irish, Poles, and Russians, among others)? It seems so.

It’s hard to find the underlying rationale for what appears, and what doesn’t, in these two ethnoracial questions. We will discuss in detail the absence of a coherent rationale. As an astute scholar has written, the Census Bureau “has no choice but to rely on incoherent categories if it hopes to measure race in the United States” because, he continues, “race arises out of (fundamentally irrational) social practices.”1 A large part of the story told in the chapters to follow explains how “incoherent categories” result in incoherent statistical races, which derive not only from social practices but equally from policy goals.

It matters if America measures races, and then, of course, how the government decides what those races are. It matters because law and policy are not about an abstraction called race but are about races as they are made intelligible and acquire their numerical size in our statistical system. When we politically ask why black men are jailed at extraordinarily high rates, whether undocumented Mexican laborers are taking jobs away from working-class whites, or whether Asians have become the model minority in America, we start from a count of jailed blacks, the comparative employment patterns of Mexicans and whites, and Asian educational achievements. When our political questions are shaped by how many of which races are doing what, and when policies addressing those conditions follow, we should worry about whether the “how many” and the “which races” tell us what we need to know about what is going on in our polity, economy, and society. We should worry about whether we should have statistical races at all, and if so, whether we have the right ones. My answer, worked out in chapter 11, argues for incrementally transforming our racial statistics in order to match them with the governing challenges of the twenty-first century. This argument, and the tactical advice offered to realize it, makes sense only in the context of a historical account of statistical races.

Chapter 2 starts with basics that frame this American history. A German doctor in 1776 divided the human species into five races. Today, nearly two and a half centuries later, these are the same five races into which the U.S. Census divides the American population, making America the only country in the world firmly wedded to an eighteenth-century racial taxonomy. Embedded in this science were theories of a racial hierarchy: there were not just different races but superior and inferior races. American politics and policy held onto this assumption for nearly two centuries.

The next section covers the nineteenth century, showing how assumptions of racial superiority and inferiority tightly bound together statistical races, social science, and public policy.

POLICY, STATISTICS, AND SCIENCE JOIN FORCES

The starting point—as is true of many features of American government—takes us to constitutional language (chapter 3). The U.S. Constitution required a census of the white, the black, and the red races.2 The founders faced an extraordinary challenge—how to join the original thirteen colonies into a republic of “united states.” They met this challenge with a political compromise that brought slaveholding states into the Union. Without this statistical compromise there would not have been a United States as we know it today. In the early censuses slaves were counted as three-fifths of a person, a ratio demanded by slaveholder interests as the price of joining the Union. Holding their noses, the northern states agreed. A deep policy disagreement at the moment of founding the nation was resolved in the deliberate creation of a statistical race. In this case, the policy need shaped the statistical practice.

Later in American history the reverse frequently occurred. Specific policies—affirmative action, for example—took the shape they did because the statistical races were already at hand. One of my major arguments, especially starting with chapter 8, is that we should learn a lesson from the founding period: start with agreement on public purposes and then design suitable statistics to meet policy challenges. Without clarity on why the nation should measure race, clarity on what to measure is impossible.

The political understanding in the nineteenth century that counting the population by race could do nationally significant policy work led naturally to a close partnership between race science and census statistics, setting the stage for what 150 years later we call evidence-based policy. It’s a fascinating if also depressing story, resting as it does on the near universal assumption that there is a biologically determined racial hierarchy: whites at the top, blacks at the bottom, with the yellow, red, and brown races arrayed between. Chapter 4 tells the race science story, giving emphasis to features that mark American history to the present day. Among the mo...