![]()

A POET’S FABLE

EARLY IN 1529 a London lawyer, Simon Fish, anonymously published a tract, addressed to Henry VIII, called A Supplication for the Beggars. The tract was modest in length but explosive in content: Fish wrote on behalf of the homeless, desperate English men and women, “needy, impotent, blind, lame and sick” who pleaded for spare change on the streets of every city and town in the realm.1 These wretches, “on whom scarcely for horror any eye dare look,” have become so numerous that private charity can no longer sustain them, and they are dying of hunger.2 Their plight, in Fish’s account, is directly linked to the pestiferous spread throughout the realm of beggars of a different kind: bishops, abbots, priors, deacons, archdeacons, suffragans, priests, monks, canons, friars, pardoners, and summoners.

Simon Fish had already given a foretaste of his anticlerical sentiments and his satirical gifts. In his first year as a law student at Gray’s Inn, according to John Foxe, one of Fish’s mates, a certain Mr. Roo, had written a play holding Cardinal Wolsey up to ridicule. No one dared to take on the part of Wolsey until Simon Fish came forward and offered to do so. The performance must have been impressive: it so enraged the cardinal that Fish was forced “the same night that this Tragedy was played” to flee to the Low Countries to escape arrest.3 There he evidently met the exile William Tyndale, whose new English translation of the Bible, inspired by Luther, he subsequently helped to circulate. At the time he wrote A Supplication for the Beggars, Fish had probably returned to London but was in hiding. He was thus a man associated with Protestant beliefs, determined to risk his life to save the soul of his country, and endowed, as were many religious revolutionaries in the 1520s and 1530s, with a kind of theatrical gift.4

In A Supplication for the Beggars, this gift leads Fish not only to speak on behalf of the poor but also to speak in their own voice, crying out to the king against those who have greedily taken for themselves the wealth that should otherwise have made England prosperous for all of its people. If his gracious majesty would only look around, he would see “a thing far out of joint” (413). The ravenous monkish idlers “have begged so importunately that they have gotten into their hands more then the third part of all your Realm.” No great people, not the Greeks nor the Romans nor the Turks, and no ruler, not King Arthur himself, could flourish with such parasites sucking at their lifeblood. Not only do they destroy the economy, interfere with royal prerogative, and undermine the laws of the commonwealth, but, since they seduce “every man’s wife, every man’s daughter and every man’s maid,” they subvert the nation’s moral order as well. Boasting among themselves about the number of women they have slept with, the clerical drones carry physical and moral contagion—syphilis, leprosy, and idleness—through the whole commonwealth. “Who is she that will set her hands to work to get three pence a day,” the beggars ask, “and may have at least twenty pence a day to sleep an hour with a friar, a monk, or a priest?” (417). With a politician’s flair for shocking (and unverifiable) statistics, Fish estimates the number of Englishwomen corrupted by monks at 100,000. No one can be sure, he writes, that it is his own child and not a priest’s bastard who is poised to inherit his estate.

Why have these diseased “bloodsuppers” succeeded in amassing so much wealth and power? Why would otherwise sensible, decent people, alert to threats to their property, their health, and their liberties, allow themselves to be ruthlessly exploited by a pack of “sturdy idle holy thieves” (415)? The question would be relatively easy to answer were this a cunningly concealed crime or one perpetrated on the powerless. But in Fish’s account virtually the entire society, from the king and the nobility to the poor housewife who has to give the priests every tenth egg her hen lays, has been openly victimized. How is it possible to explain the dismaying spectacle of what Montaigne’s friend, Etienne de la Boétie, called “voluntary servitude”?5

For la Boétie (1530–1563) the answer is structural: a chain of clientage and dependency extends and expands geometrically, he argues, from a small number of cynical exploiters at the top to the great mass of the exploited below.6 Anyone who challenges this system risks attack, both from the few who are actually reaping a benefit and from the many who are deceived into thinking that their interests are being served. Individuals may actually grasp that they have been lured into voluntary servitude, but as long as they have no way of knowing who else among them has arrived at the same perception, they recognize that it is dangerous to speak out.

If those who see through the lies could share their knowledge with other, like-minded souls, as they long to do, they could take the steps necessary to free themselves from their chains. Those steps are remarkably simple: what is needed, in fact, is not a violent uprising but a quiet refusal. Since only a minuscule fraction of the society is truly profiting from the system, all it would take, were there widespread enlightenment, is peaceful noncooperation. When the king demands his breakfast, one need only refuse to bring it. He may sputter in rage, but the rage will be as inconsequential as an infant’s, provided that the great majority of men and women have collectively determined to be free. But how is that determination to be fostered? How is it possible for those who understand the situation to awaken others, so that all can act in unison? As long as they remain isolated, there is little that enlightened individuals can do, and it is risky for them to open their secret thoughts to others. If only there were little windows in each person, la Boétie daydreams, so that one could see what is hidden inside and know to whom one could safely speak.

For Etienne de la Boétie, the first and fundamental problem is to account for widespread behavior that seems so obviously against interest, and not simply against the marginal or incidental concerns of particular groups but against the central material and sexual preoccupations of all human societies. Why do people allow themselves to be robbed and cheated? Simon Fish is grappling with the same problem, but his answer centers not on social structures or institutions or hierarchical systems of dependency. After all, very few people think of themselves as actually dependent on the lazy, syphilitic monks and friars who shamelessly take advantage of them. These so-called holy men are not conspicuous figures of wealth or might; on the contrary, unarmed and unattended, they dress poorly and go about begging. In Fish’s account their place at the center of a vast system of pillaging and sexual corruption relies upon the exploitation of a single core conviction: Purgatory.

ALMS FOR THE DEAD

Fish was not alone in his theory. Elsewhere in the writings of the early Reformers, we find similar claims for the overwhelming importance of the doctrine of Purgatory, a doctrine already long under attack in England by those heretics known as Lollards.7 “In God’s name, tell me,” the king asks the impoverished Commonality in the tragedy King Johan by John Bale (1495–1563), “how cometh thy substance gone?” To which Commonality replies, “By priests, canons and monks, which do but fill their belly, / With my sweat and labor for their popish Purgatory.”8 Tyndale similarly writes of the churchmen that “[a]ll they have, they have received in the name of Purgatory … and on that foundation be all their bishoprics, abbeys, colleges, and cathedral churches built.”9

The claim obviously serves a Protestant polemical purpose by loading the immense weight of the entire Catholic Church upon one of its most contested doctrines, but in the heated debates of the sixteenth century, at least some English Catholics agreed. Writing in the 1560s in defense of Purgatory, Cardinal William Allen (1532–1594) claims that “this doctrine (as the whole world knoweth) founded all Bishoprics, builded all Churches, raised all Oratories, instituted all Colleges, endowed all Schools, maintained all hospitals, set forward all works of charity and religion, of what sort soever they be.”10 Though it received its full doctrinal elaboration quite late—the historian Jacques Le Goff places the “birth of Purgatory” in the latter half of the twelfth century11—the notion of an intermediate place between Heaven and Hell and the system of indulgences and pardons meant to relieve the sufferings of souls imprisoned within it had come to seem, for many heretics and orthodox believers alike, essential to the institutional structure, authority, and power of the Catholic Church.

This degree of importance is certainly an exaggeration, but it is not a complete travesty: by the late Middle Ages in Western Europe, Purgatory had achieved both a doctrinal and a social success. That is, it was by no means exclusively the esoteric doctrine of theologians but part of a much broader, popular understanding of the meaning of existence, the nature of Christian faith, and the structure of family and community. Hence, to cite a single English example, the various fifteenth-century devotional treatises known collectively as The Lay Folks Mass Book include for recital after the elevation of the Host a vernacular prayer for the dead. The faithful pray for those souls, “father soul, mother soul, brother dear, sisters souls, sib men and other sere [relatives and other particular individuals],” who may be suffering in “Purgatory pain.”12 The prayer—from a text that is not a piece of the official liturgy but a model of private, vernacular faith, intended to be read while the priests conduct the Latin Mass—pleads that bonds shackling these dead be unlocked, so that they can pass from torment to everlasting joy.

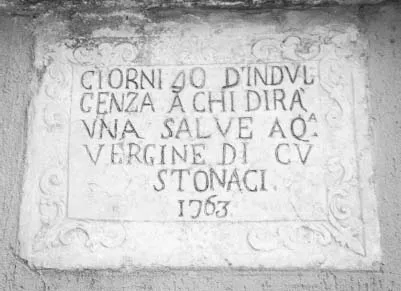

The simple English prayer is evidence—to which much more could be added—that the attempt to free souls from the prison house of Purgatory was not exclusively the work of a priestly class of specialists. There was such a class, large in numbers, as Fish and other Protestant polemicists stridently insisted, whose maintenance cost a considerable amount of money. But their rituals, though regarded as particularly efficacious, were not the only assistance that the dead could receive, and lay persons could supplement the liturgical ceremonies that their donations sponsored with a variety of less formal (and less expensive) acts on behalf of their loved ones and themselves. In Catholic countries that did not pass through periods of iconoclastic violence, one can still see, particularly in small towns, many traces of this popular piety, often accorded formal, if grudging, recognition by the church. Thus, for example, embedded in the stone walls along the narrow lanes of Erice, in western Sicily, there are numerous small, rather crude votive images beneath which elegant inscriptions, dating for the most part from the eighteenth century, promise the remission of periods of purgatorial suffering for those who stand before the images and recite prayers (fig. 1). I asked a local resident once, an elderly woman, whether people still stopped and said the ritual words. No, she replied, not any more. Was that, I inquired, because the practice was now regarded as superstitious? Not at all, she said; the priests now wanted you to pay for prayers in church. To be sure, these prayers were much more powerful, but they were too expensive, and everyone she knew had stopped buying them. But if the price came down, she added, more people would certainly want them.

Fig. 1. “40 days of indulgence” Votive plaque beneath image of Virgin, Erice, Sicily. Photo: Stephen Greenblatt.

Along with private fasts and vigils, such prayers—casual, informal, recited in the streets—certainly did not replace the proper intercessory gestures provided for by the “pious bequests” made in large numbers of wills, but they do clearly indicate that the task of assisting the soul’s passage to bliss was not entrusted entirely to the certified authorities on the afterlife. Nonspecialists understood that they could do things in their everyday lives to ease the pain of those they loved or to shorten their own anticipated share of postmortem pain.

Charity to the dead, whether performed privately or in public, by lay persons or by priests, began at home. But the effort to alleviate suffering extended beyond the immediate circle of self, family, and friends to “all Christian souls.” On All Hallows’ Eve, before All Saints’ Day (November 1), bells rang throughout the night in English towns and villages, as communities joined in prayers for the whole, vast company of the dead, and on the day following, All Souls’ Day (November 2), it was customary to distribute “soul cakes.” John Mirk, canon of Lilleshall, Shropshire, in the mid–fifteenth century, lamented that the custom of giving bread for the souls of the dead—“hoping with each loaf to get a soul out of Purgatory”—was in decline, but it evidently survived, at least in rural areas, into the eighteenth century.13 The Sarum Prymer of 1538 includes “A prayer to God for them that be departed, having none to pray for them.” These are soul...