![]()

CHAPTER 1

Beyond Economism

Workers flood the streets to protest government policy. They shut down businesses and public offices. This describes moments in nineteenth-century America; it certainly captures recent events in parts of Europe, Asia, and the American Midwest. While all unions are involved in politics to some degree, large-scale political strikes are rare in the contemporary Anglo-Saxon democracies, and rarer still is the use of industrial action for political ends. Variation in the size, form, and goals of political mobilization is the subject of countless studies. The most interesting tend to focus on the collective actions of those who are marginalized—be they African Americans in the United States or peasant farmers in China—or those engaged in out-and-out rebellion or revolution against the state. This book raises a somewhat different puzzle.

We ask why some organizations move beyond the particular and particularized grievances that are the raison d’être of the organization and engage in political actions, especially those that have little or nothing to do with members’ reasons for belonging. For example, in the late 1930s, dockworker unions in Australia and on the West Coast of the United States refused to load scrap iron bound for Japan, in protest against the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. These unions continue to periodically engage in work stoppages or boycotts in opposition to national foreign policy or to assist in freedom struggles overseas.

We explore the variation in organizational norms, governance arrangements, and social networks that produce systematic differences in aggregate behavior. We also explain why members go along. Left-wing longshore union members give up time and money to fight on behalf of social justice causes from which they can expect no material return. Parishioners of churches throughout the United States risk jail to shelter asylum seekers. Altruism is common enough, and so are volunteering, political commitment, and unselfish service to others. Yet, we know that there are environments that evoke such behavior and those that depress it. Why and how do some organizations produce membership willingness to self-sacrifice on behalf of a wide range of political and social justice issues? In some instances, the answer may be simple: self-selection. Those who want to act on behalf of others join the church or the interest group or the activist organization that encourages, indeed advertises, such behavior. The more interesting cases are those in which individuals join for one reason but come to pursue goals they may not have considered previously. Membership changes them. It shapes their identity and choices.

Part of the answer lies in how an organization defines its community of fate (Levi and Olson 2000), those with whom individuals come to perceive their own interests as bound and with whom they are willing to act in solidarity.1 This term is more than a rhetorical flourish. It embodies two distinct but interrelated concepts. The community identifies those whose situations organizational members see as distinct possibilities for themselves. An individual looks at others and imagines “there, but for the grace of God, go I.” But more than simple human recognition is the entwining of fate. The community of fate identifies those the organizational members perceive as engaged in similar struggles for similar goals. Organizational members view their welfare as bound up with that of the community. It is a short jump to see how defining a community of fate has strong implications for the organization’s scope of legitimate action. The community of fate may encompass only members of the organization, in which case its actions will be narrow and exclusively self-serving. But the community of fate could encompass unknown others for whom the members feel responsibility. These external others need not recognize or even know about the organization.

A community of fate requires recognition of common goals and enemies, and it is strengthened by interdependence. Social interactions, education, and the transmission of credible information by leadership shape common beliefs about what actions are possible for the organization and its members. Perceived interdependence is a function of immediate social, work, and residential networks, but it can also result from learning about distant events and connecting them to local possibilities.

Organizations successful at encouraging costly actions that transcend narrow self-interest are worthy of note in their own right. They also offer insight into the processes that foster aggregate behavior and, possibly, changes in beliefs and preferences. An extensive literature exists on the factors affecting individual choice and the aggregation of individual preferences into collective outcomes. We build on that scholarship to understand the factors that encourage individuals to act in ways they may not have considered, let alone gone along with, prior to their engagement in a particular organization.

In attempting to explain the conditions under which organizational membership transforms individual action, altering aggregate behavior, we reframe the question that motivated Lenin in What Is to Be Done? (1963 [1902]). Lenin wanted workers to think beyond their own immediate needs, to imagine a society in which a different life was possible, and then to engage in revolution to achieve it. Workers are relatively easily persuaded to fight for improvements in wages, hours, and working conditions. For Lenin, such goals constitute “economism,” a focus on the narrow economic interests bound up in the job. He wanted to transform the preferences, beliefs, and actions of the working class. His aim was to create class-conscious workers who understood their fate as bound up with each other across occupations and even borders, workers who realized their struggle had to be over far more than their working conditions and pay. Lenin held that only in this way could the proletariat become victorious, significantly improving their material well-being while also achieving a more equitable society.

Lenin proposed political education as the way to inspire workers. He advocated a workers’ newspaper to convey information, and he encouraged other socialization processes to make workers aware of and sensitive to the salience of political projects near and dear to the revolutionaries’ hearts.2 His strategy, developed within an authoritarian and repressive context, also included the organization of the revolutionaries into cells, with very few individuals knowing each other. He was eager to prevent the regime from locating and jailing the Communist Party activists.

Predating Lenin and operating within a democratic framework, Frederick Engels argued that ballots might transform capitalism into socialism. However, confidence in electoral victories stumbled on the very problem Lenin identified: workers were more committed to achieving immediate material benefits than long-term changes that might come at a significant price (Przeworski 1985). The empirical reality is that middle-class and well-off proletariat voters reveal little interest in overturning the economic system (Przeworski and Sprague 1986; Ziblatt 2014).

Mobilizing the proletariat to engage in revolution is not what is at issue for us in this book, but we do care about the conditions that change individual beliefs and actions. While we can dismiss Lenin’s model of revolution, we cannot so easily dismiss the central question he raises: What motivates members of organizations developed to serve the interests of their membership to choose to engage in actions on behalf of a larger whole? Nor can we easily dismiss some of Lenin’s insights, namely the critical role of leadership, education, and information. Our research reinforces the importance of these factors in empowering members to act in ways they may not previously have thought viable.

Some scholars focus on structural factors and political opportunities that make it more or less likely for a group to act and to act in a certain way. The principal contemporary exemplar of this analytic tradition is the resource mobilization literature (Lipsky 1968; Tilly 1978; Zald and McCarthy 1979; Tarrow 1994) and its more recent contentious politics variant (McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly 2001). While our approach shares much in common with the contentious politics perspective, our focus is more squarely on the micro-foundations of behavior and the strategic interactions between the leaders and followers and among the followers themselves. Consistent with recent work by Bueno de Mesquita (2010), we claim that leaders need to convince followers that they can succeed, which in turn requires a demonstration that enough others share the leaders’ sentiments about appropriate actions and are willing to act when necessary.

One way to think about this set of issues, of course, is through models of collective action, particularly those that suggest the various dilemmas that exist for those deciding whether to cooperate or contribute (see, e.g., Lichbach 1995, 1997). Mancur Olson (1965), James Q. Wilson (1973), and many others emphasize selective incentives, largely material but also solidary and ideological. Selective incentives certainly play a role in accounting for certain kinds of contributions; indeed, Olson discussed union dues–paying as a primary example of how selective incentives work in practice. Others emphasized leadership as a means for providing and targeting selective incentives (Frohlich, Oppenheimer, and Young 1971). What selective incentives cannot adequately explain is how encompassing communities of fate are or how governance and norms influence group choice. Rational choice models, particularly the new economic institutionalism (North 1990; Ostrom 1990), get us a little further by considering how rules constrain or facilitate behavior. Behavioral economics provides even more clues with its focus on social preferences, such as ethical commitments and altruism. Considerations of when prosocial preferences are crowded out by material incentives (Bowles and Polanía-Reyes 2011) and the extent to which social context influences this process (Fehr and Hoff 2011) are related to the issues we raise here.

Our question and approach also have much in common with the large sociological literature on group mobilization and collective action.3 Though we build on several insights in this literature, we differ in that our concern is not so much with cooperation in discrete, well-defined activities. Rather, we emphasize how groups already recognizing a mutual interest come to expand their scope of action to act on behalf of those outside the group. That is, we make endogenous the projects a group is willing to undertake. A central issue here—one that is less explored in the sociological literature—is how such commitments can be maintained and reproduced through time in the context of formal organizations.

Our approach is to identify the aggregate behaviors that result from interactions between leaders and followers, as mediated by organizational institutions. Although we rely on both game theory and economic models, ours is a highly contextual account emphasizing the beliefs of the leaders, the settings they create as well as inherit, and the beliefs, networks, and responses of the members. Unlike most of the work in the literatures from which we primarily draw, we do not presume that individuals already have clear preferences. We are open to the possibility that preferences change as a consequence of membership. At the least, preferences are clarified and, possibly, reordered as members come to believe that certain goals are actionable and potentially achievable.

Our Argument

We explore our puzzle in the context of labor unions, focusing on variation in unions’ use of industrial power for political ends. A union’s bargaining power ultimately lies in the members’ ability to coordinate in withholding labor from employers.4 Most unions maintain some contact with politicians and political authorities. Nevertheless there is variation across unions in both the extent of political mobilization and their industrial success. Most unions, not surprisingly, strike rarely and then only to promote the wages, hours, benefits, job security, and working conditions of members, or even specific subsets of members (Golden 1997). Many unions also lobby for protective legislation or forms of social insurance from which they will benefit. At the extreme end of both continua are unions that use their industrial power in the service of political ends having virtually nothing to do with their own conditions. They do not give up their social movement energy as Michels (1962 [1919]) predicted or displace their goals as Merton (1968 [1957]) observed.

But why do they behave this way and how do they sustain it? To state the main thesis of the first part of the book: sustained political mobilization requires an ideologically motivated founding leadership cohort who devises organizational rules that facilitate both industrial success and coordinated expectations about the leaders’ political objectives. The result is contingent consent (Levi 1997): members will willingly, sometimes enthusiastically, go along with leadership demands as long as they are convinced that they are receiving the material benefits the organization promised them upon joining, that the leadership is accountable, and that enough other members are also going along. In the second half of the book, we explore the claim that members come to hold the belief (or at least act consistently with the belief) that their fate is intertwined not only with their associates in the organization but also with a larger population; by helping others, they are helping themselves. This may also require them to focus on long-term goals in addition to immediate aims. Interactions among the members, the capacity to challenge leadership arguments and demands, and attachments to the organizational traditions are the factors that produce both contingent consent with leadership and a more encompassing community of fate.

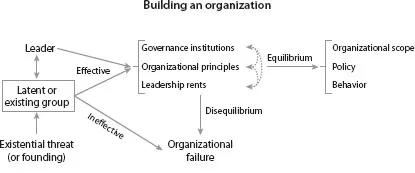

Figure 1.1 outlines schematically the first part of our argument, identifying the major actors, variables, and outcomes that we discuss in subsequent chapters. We begin at a moment of organizational founding or crisis. At such times a leader who devises tactical solutions to the threats confronting the organization has an outsized opportunity to design subsequent organizational governance institutions, defined as the formal rules and informal norms that delineate how decisions are taken, how the organization will respond to future events, and how and on what basis organizational members should evaluate the actions of leaders. But there is no guarantee that effective leaders will emerge. A persuasive leader could arise and drive the organization off a cliff with the wrong policies or weak governance institutions. Or perhaps the challenges facing the organization are simply insoluble. In these cases, the organization will fail.

All the leaders we investigate are asking members to act on behalf of material interests, but some are also asking members to act on behalf of political or ethical goals that have little or nothing to do with the reasons for joining the voluntary organization. Variation in leaders’ political commitments is not the object of explanation here; we take the leaders’ preferences as exogenous. Our explanation emphasizes the processes by which leadership earns the confidence of members and then succeeds in persuading them to act on behalf of goals the leadership argues are important. The leader attempts to convince members that their own fate hinges on achievement of ends that serve external others as well as themselves. Successful leaders effect their ends through a four-step process: (1) achievement of the economic goals of the union; (2) the announcement of principles the leaders pledge to uphold; (3) the creation of governance arrangements that allow leadership and members to effectively coordinate; and (4) processes and institutions that either induce consensual maintenance of the principles or compel members to act as if they consent. Numbers 2, 3, and 4 on this list are components of the organizational governance institutions.

Figure 1.1: The founding argument in schematic form

Nearly all unions, indeed most organizations, have governance institutions in this sense. However, not all organizational governance institutions emphasize acting beyond material self-interest. That, we argue, requires leadership commitment to political causes. More generally we argue that leadership is costly and difficult. Those who undertake to lead do so not only for the benefit of the organization but also because they themselves have other desires and objectives—monetary, social, or political. Organizational members will be willing to contribute to the leader’s “rents” so long as the leader continues to serve the members well. The founding leaders at these pivotal moments are in unique positions to establish the form and level of leadership rents. Where these founding leaders are politically motivated, the resulting leadership rents will be such that the leader is able to ask for member mobilization for political causes, up to a point.

We claim that these features—form and level of leadership rents, organizational principles, and governance institutions—form, loosely speaking, an equilibrium in which they are all self-reinforcing...