![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Biodiversity and Plant-Animal Coevolution

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The almost-perfect matching between the morphology of some orchids and that of their insect pollinators fascinated Charles Darwin, who foresaw that the reproduction of these plants was intimately linked to their interaction with the insects (Darwin, 1862). Darwin even predicted that the extinction of one of the species would lead to the extinction of its partner:

If such great moths were to become extinct in Madagascar, assuredly the Angraecum would become extinct (Darwin, 1862, p. 202).

Later on, Alfred Russell Wallace would take the examples of plant-animal interactions to illustrate the force and potential of natural selection to shape phenotypic traits. He already noted that the selective pressures derive directly from the interaction itself (Wallace, 1889).

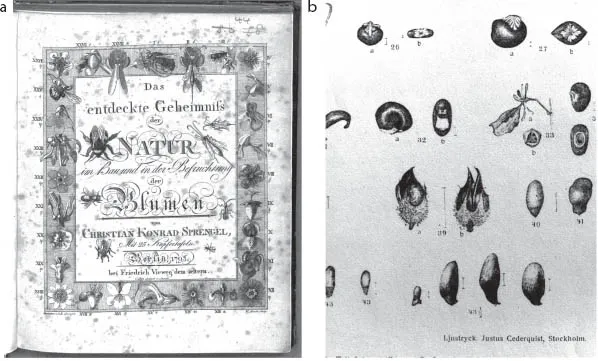

The fascinating experimental work by Darwin on plant sexuality was very influenced by the earlier work of Sprengel (1793) demonstrating the role of insects in plant fertilization (Fig. 1.1a). Similarly, his work on hybridization shows the strong influence by Köllreuter (1761; see Waser 2006, for a historical overview). Köllreuter already documented the diversified pollination service that multiple insect species provide to plants. However, the major advances at that time in documenting the specificity of pollination patterns are due to the monumental work of Müller, Thompson, et al. (1883), providing the list of pollinator species for 400 plant species, and Knuth (1898), reporting records for more than 6000 species. Early researchers on plant-seed disperser interactions (Hill, 1883; Beal, 1898; Sernander, 1906) also emphasized the diversity and subtleties of mutual dependencies among the partners and provided well-grounded evidence for mutual coadaptations between them (Fig. 1.1b). Beal provides an analogy with pollination systems, quoting Darwin’s orchid book (Darwin, 1862):

FIGURE 1.1. The work by early botanists and zoologists represented the foundations for later studies on mutualistic interactions. Prominent among them was a series of monographs on different types of interactions (pollination, seed dispersal, ant-plants, etc.) appearing between the late 1700s and early 1900s. (a) The beautifully detailed front page of Sprengel, the author of an important monograph on flowers and pollination (Sprengel, 1793); (b) detailed view of one of the plates illustrating Sernander monograph on seed dispersal by ants (Sernander, 1906), showing the anatomical details of elaiosomes (reward tissue) attached to the seeds.

The more we study in detail the methods of plant dispersion, the more we shall come to agree with a statement made by Darwin concerning the devices for securing cross-fertilization of flowers, that they “transcend,” in an incomparable degree, the contrivances and adaptations which the most fertile imagination of the most imaginative man could suggest with unlimited time at his disposal (Beal, 1898, p. 88).

The complexity that such interactions could take was already recognized by Darwin in the final paragraphs for the first edition of on the Origin:

It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us (Darwin, 1859, p. 498).

Similarly, in Chapter III, Struggle for Existence, we can read:

I am tempted to give one more instance showing how plants and animals, most remote in the scale of nature, are bound together by a web of complex relations (Darwin, 1859, p. 73).

Darwin also envisioned the mutually reciprocal effects involved in the pollination of red clover by “humble-bees” and the potential effects of declines in pollinator abundance. He foresaw the complexity of mutualistic networks, a complexity that precluded a community-wide approach.

Mutualism and symbiosis became quickly incorporated into the research agenda after de Bary (1879) coined the term symbiosis to account for interactions among two or more dissimilar entities living in or on one another in intimate contact. These developments of the study of mutualisms were well grounded on the empirical evidence obtained by botanists documenting every detail of the morphological structures of flowers, fruits and seeds (Fig. 1.1) as well as the intricacies of the interactions with animals. Since then, a myriad of scientific papers have described the mutually beneficial (mutualistic) interactions between plants and their animal pollinators or seed dispersers. But the interest of ecologists and evolutionary biologists in mutualistic interactions has been quite variable in emphasis and prevalence during this period of time.

Work on mutualism, like the analysis by Pound (1893), remained marginal to dominant views in ecology. Antagonistic interactions were at the core of Clements and Tansley’s views of plant ecology, which dominated the field in the United States and United Kingdom during the early 20th century. This was paradoxical given the rapid discovery of new major symbiotic interactions like mycorrhizae in the 1880s and 1890s (Schneider, 1897). In fact, a few years after the Lotka-Volterra models were developed for antagonistic interactions, Gause and Witt (1935) proposed dynamic models of mutualism based on very similar formulations. However, mutualistic interactions were ignored in the extensive treatment that Volterra and D’Ancona (1935) dedicated to the dynamics of “biological associations” among multiple species. Up to the early 1970s, mutualism was not at the center of ecological thinking (L. E. Gilbert and Raven, 1975), which was more focused on the dynamics of antagonistic interactions such as predation and competition as the major forces driving community dynamics.

Most recent textbooks on ecology and evolution just treat mutualisms as iconic representations of amazing interactions among species, lacking a formal conceptual treatment at a similar depth to predation or competition (Sapp, 1994). Boucher (1985a) provides a lucid analysis for the reasons why mutualism had a marginal importance in ecological studies up to the late 1970s and early 1980s, when dynamic and genetic models of mutualistic interactions started to be revisited (May, 1982). Among these reasons, there are the technical difficulties to find stable solutions for dynamic models of mutualism (May, 1973) and the lack of appropriate empirical and theoretical tools to develop a synthesis of the enormous diversity of mutualistic interactions (May, 1976). Also, the association of the idea of mutualism with anarchist thinking related to the 1902 book Mutual Aid by Peter Kropotkin most likely had an influential effect on the demise of mutualism in the early 1900s and its marginal consideration (Boucher, 1985a).

Ehrlich and Raven, in their classic paper, emphasized the pivotal role of plant-animal interactions in the generation of biodiversity on Earth (Ehrlich and Raven, 1964). Interestingly enough, insects and flowering plants are among the most diverse groups of living beings, and it is assumed that the appearance of flowering plants opened new niches for insect diversification, which in turn further spurred plant speciation (Farrell, 1998; McKenna, Sequeira, et al., 2009). This scheme has some alternative explanations, such as that one group may have been tracking the previous diversification of the other one without affecting it (Ehrlich and Raven, 1964; Pellmyr, 1992; Ramírez, Eltz, et al., 2011). However, the relevant point is that animal-pollinated angiosperm families are more diverse than their abiotically pollinated sister-clades (Dodd, Silvertown, et al., 1999).

Since the seminal paper by Ehrlich and Raven (1964), there has been a flourishing of studies on plant-animal interactions in general and on mutualisms among free-living species in particular. A significant amount of this work stems from recent advances in the study of coevolutionary processes (Thompson, 1994, 1999a) and the recognition of their importance in generating biodiversity on Earth.

Fortunately, there is ample fossil evidence of the origin of mutualistic interactions. Thus, the first preliminary adaptations to pollination can already be tracked around the mid-Mesozoic, almost 200 million years ago, and became widely observed from the mid-Cretaceous, more than 100 million years ago (Labandeira, 2002). In relation to seed dispersal, the early evolution of animal-dispersed fruits in the upper Carboniferous, together with the diversification of small mammals and birds in the Tertiary, allowed the diversification of plant fruit structures and dispersal devices (Tiffney, 2004). Therefore, multi-specific interactions among free-living animals and plants have been an important factor in the generation of biodiversity patterns for a very long time.

But mutualisms have been important not only in the past. They remain important in the present. Mutualisms among free-living species are one of the main wireframes of ecosystems, simply because extant ecosystems would collapse in absence of animal-mediated pollination or seed dispersal of the higher plants. Effective pollen transfer among individual plants is required by many higher plants for successful fructification, and active seed dispersal by animal vectors is a key demographic stage for maintaining forest regeneration and dynamics. Both processes depend on the provision by plants of some type of food resource that animals can obtain while foraging. These plant resources (nectar, pollen, fleshy pulp, seeds, or oil) are fundamental in different types of ecosystems for the maintenance of animal diversity through their keystone influence on life histories and annual cycles.

From a conservation point of view, hunting and habitat loss are driving several species of large seed dispersers toward extinction, and these effects cascade towards a general reduction of biodiversity through reductions in seed dispersal (Dirzo and Miranda, 1990; Kearns, Inouye, et al., 1998; S. J. Wright, 2003). Looking back through time, evidence for these effects comes from the fossil record. Episodes of insect diversity decline, such as the ones during the Middle to Late Pennsylvanian extinction, during the Permian event, and at the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary, have been followed by major extinctions of flowering plants (Labandeira, 2002; Labandeira, Johnson, et al., 2002). All this evidence already suggests that in conservation we cannot treat these species isolated from each other or consider only pairs of interacting species. Rather, we need to have a network perspective.

The first studies on mutualism focused on highly specialized one-to-one interactions between one plant and one animal (Johnson and Steiner, 1997; Nilsson, 1988). Examples of these highly specific pairwise interactions are Darwin’s moth and its orchid (Darwin, 1862; Nilsson, Jonsson, et al., 1987), long-tongued flies and monocot plants (Johnson and Steiner, 1997), fig wasps and figs (Galil, 1977; Wiebes, 1979; J. M. Cook and Rasplus, 2003), and yucca moths and yuccas (Pellmyr, 2003). However, their strong emphasis in evolutionary studies probably reflects more the aesthetics of such almost perfect matching than their frequency in nature (Schemske, 1983; Waser, Chittka, et al., 1996). Motivated by this fact, several authors already advocated a community context to address mutualistic interactions (Heithaus, 1974; Feinsinger, 1978; Janzen, 1980; Herrera, 1982; Jordano, 1987; Fox, 1988; Petanidou and Ellis, 1993; Bronstein, 1995; Waser, Chittka, et al., 1996; Iwao and Rausher, 1997; Inouye and Stinchcombe, 2001).

Waser, Chittka, et al. (1996) made the point that generalism is widespread in nature and advanced conceptual reasons based on fitness maximization in highly fluctuating interaction environments. More recently, and as a consequence of this interest in expanding the pairwise paradigm, there has been significant progress in our understanding of how pairwise interactions are shaped within small groups of species across time and space (Thompson and Pellmyr, 1992; Thompson, 1994; Parchman and Benkman, 2002).

A BIT OF NATURAL HISTORY

Mutualisms are assumed to be among the most omnipresent type of interaction in terrestrial communities (Janzen, 1985). Beyond the mutualistic interactions among conspecific individuals (i.e., the subject of kin-selection and parent-offspring interactions), most of these interactions are allospecific interactions, involving species, or sets of species, completely unrelated. Multispecific interactions involving mutual benefits among partner species are extremely widespread and involve all the terrestrial vertebrates, plants, and arthropods. Many of these mutualisms involve sets of animal species interacting with plant species.

Only five major groups of multispecific mutualisms exist in natural terrestrial ecosystems: (1) pollination and (2) seed-dispersal mutualisms among animals and plants (Jordano, 1987); (3) protective mutualisms among ants (and sometimes other arthropods) that protect plants and homopterans (Rico-Gray and Oliveira, 2007); (4) harvest mutualisms, including the gut flora and fauna of all vertebrate species and many invertebrates, the root rhizosphere occupants, lichens, decomposers, epiphyllae and some epiphytes, and ant-plants (ant-feeding plants; L. E. Gilbert and Raven 1975; Janzen 1985; Rico-Gray and Oliveira 2007). A fifth type of mutualism is the interaction between humans and plants (agriculture) and animal husbandry (Boucher, 1985b), mediated by the domestication process. Facilitative interactions among plants can also be considered as a type of mutualism with beneficial consequences for both partners (Verdú and Valiente-Banuet, 2008), although in many cases the positive effects occur only during specific stages (e.g., facilitation of seedling establishment).

In this book we focus on pollination and seed dispersal with brief excursions into protective and ant-plant mutualisms (Fig. 1.2). The reason for this choice is because this is where the majority of research on mutualistic networks has focused and is where our expertise lies. Still, there is no evidence to suggest that the same rules do not apply to other mutualistic networks.

FIGURE 1.2. Examples of plant-animal mutualisms illustrating interactions among free-living species. These mutualisms typically involve the harvesting of plant resources by animal species with outcomes of fitness gain directly derived from the interaction. Clockwise from top right: Tangara cyanocephala swallowing a Campomanesia (Myrtaceae) berry (Ilha do Cardoso, SE Brazil; photo courtesy of André Guaraldo). Agouti, Dasyprocta aguti, feeding on fallen fruits of a Sapotaceae tree (Amazonia, N Brazil; camera-trap photo courtesy of Wilson Spironello). Eristalis tenax (Syrphidae) visiting an inflorescence of Allium sp. (Sierra de Cazorla, SE Spain; photo by P. Jordano). Ectatomma tuberculatum ants tending the extrafloral nectary of an Inga tree (Gamboa, Panama; photo: © Alex Wild, used with permission).

Typically, we might expect the net outcomes of mutualistic interactions among individuals or among species to fall somewhere along a gradient between antagonism (e.g., parasitism or cheating) and legitimate mutualism (Thompson, 1982). For instance, Rico-Gray and Oliveira (2007) document that ant-plant interactions most likely originated from antagonistic interactions, but the most frequent form of their ecological relationships is mutualistic. And this range can be observed in the interaction of two partner species (variation among individual effects) or when multiple species are involved (variation among species effects). For example, consider the diverse assemblage of insects visiting the flowers of a plant species. The whole range of interactions in a given population of the plant would be th...