![]()

PART ONE

Imperialisms and Colonialisms

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

From Imperium to Imperialism

WRITING THE ROMAN EMPIRE

The rise and fall of a great empire cannot fail to fascinate us, for we can all see in such a story something of our own times. But of all the empires that have come and gone, none has a more immediate appeal that the Empire of Rome. It pervades our lives today: its legacy is everywhere to be seen.

—Barry W. Cunliffe, Rome and Her Empire

The endurance of the Roman Empire is one of the success stories of history. That it survived so long is a sign of its principal achievement, whereby a heterogeneous mixture of races and creeds were induced to settle down together in a more or less peaceful way under the Pax Romana.

—J.S. Wacher, The Roman World

DEFINITIONS OF EMPIRE AND IMPERIALISM

It is generally agreed that the Roman Empire was one of the most successful and enduring empires in world history.1 Its reputation was successively foretold, celebrated and mourned in classical antiquity.2 There has been a long afterlife, creating a linear link between Western society today and the Roman state, reflected in religion, law, political structures, philosophy, art, and architecture.3 Perhaps partly in consequence, many people in the United States and Europe are curiously nostalgic about the Roman Empire in a way that has become deeply unfashionable in studies of modern empires.4

There have even been attempts to imagine a world in which the Roman Empire never ended. Some readers may be familiar with the wonderful conceit of Robert Silverberg’s novel Roma Eterna, and his imagined episodes of later Roman history, including the conquest of the Americas and extending to an attempted “space shot” in the year 2723 AUC (ab urbe condita). The global scope and extreme longevity of Silverberg’s Rome—still a resolutely pagan state at the end, having averted the rise of both Christianity and Islam—emphasizes the unedifying aspects of military dictatorship.5 Like bald narrative accounts of Roman history, these modern reimaginings blur into a catalog of wars, coups, attempted revolts, persecutions, assassinations, and murders.6 Here, of course, is the great paradox of the Roman Empire. Lauded in many modern accounts as an exemplary and beneficent power,7 it was also a bloody and dangerous autocracy.8 Of course, Rome was not the only human society prone to war and violence—much debate has been prompted by Lawrence Keeley’s War before Civilization concerning humanity’s predilection for intercommunal conflict from prehistory onward.9 However, the scale, frequency and length of wars in Roman society were undeniably unusual in a preindustrial age. Despite interesting differences from modern colonial regimes in the manner in which local elites were integrated into the imperial project, the facade of civil government was underpinned by violence, both real and latent.10

Cinematic visions of Rome have changed over the years, but in general there is a mismatch between these depictions and the rosier scholarly consensus on the Roman Empire—typically what has been highlighted in “sword and sandal epics” has been sex and violence, with the empire more often than not representing the “dark side.”11 Occasional ruminations on Rome’s decline and fall, of course, have had as much to tell us about contemporary unease about the future of the American empire.12 It remains a paradox to me that cinema has done more to challenge our preconceptions of Rome than academic study. For instance, I can think of no darker depiction of life at the sharp end of Roman power than the scourging scene in Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ.13

Definitions of imperialism and of empire are varied and controversial, so I need to make my position clear at the outset. Some commentators have argued that the imperium Romanum was quite distinct from the modern term imperialism and, in comparison with modern empires, the Roman Empire was a product of very different political and economic forces.14 A recent study has suggested that Roman expansionism fits more readily into an analytical frame of state building rather than an anachronistic back-projection of imperialism.15 Yet that seems to ignore much about Rome that was exceptional in relation to other states of classical antiquity—the nature of Rome as a cosmopolis or metropolis fits more readily into analysis of imperial systems than of other ancient cities.16 Similarly, the detail of extant Roman treaties with subject and allied peoples emphasize the extraordinary and unequal nature of these relations and the mechanisms that Rome adopted to control or to exert influence on far-flung territories.17 Furthermore, I believe that there are issues relating to the exercise of power and the responses that power evokes, where it is legitimate to draw comparisons as well as contrasts between ancient and modern. Current attempts to situate the modern United States among past empires recognize the relevance of the Roman world.18

So, let us move on to some key definitions. An empire is the geopolitical manifestation of relationships of control imposed by a state on the sovereignty of others.19 Empires generally combine a core, often metropolitancontrolled territory, with peripheral territories and have multiethnic or multinational dimensions. Empire can thus be defined as rule over very wide territories and many peoples largely without their consent. While ancient societies did not have as developed a sense of self-determination as modern states, the fact that incorporation was often fiercely contested militarily is symptomatic of the fundamentally nonconsensual nature of imperialism.

Imperialism refers to both the process and attitudes by which an empire is established and maintained. Some have argued that imperialism is essentially a modern phenomenon, though I would counter that the process existed in antiquity even if less explicitly developed in conceptual terms.20 However, just as empires evolve over time, imperialism need not be static or uniform. When we look at the dynamics of the Roman Empire, we perhaps need to look beyond the rather monolithic definitions of most accounts and to consider several distinctive phases of imperialism. We also need to beware of the tendency of both modern and ancient commentators to explain earlier phases in the light of institutions and ideologies that developed only in later phases. Imperialism should be seen as a dynamic and shape-shifting process.

Colonialism is a more restricted term that defines the system of rule of one people over another, in which sovereignty is operated over the colonized at a distance, often through the installation of settlements of colonists in the related process of colonization.21 Both words, of course, derive from the Roman term colonia, initially definable as a settlement of citizens in conquered territory.22 In recent years there has been increasing interest in the diverse nature of colonialism and colonization through the ages and the archaeological manifestations of these processes.23 We shall look in more detail at colonialism later on.

Explaining empire is much more tricky than defining it, but I think the key approach must be to explore the networks of power that sustain it. What unites all types and ages of empires is the combination of the “will to power” and the large scale at which it is expressed. The domination of others is a characteristic of human societies, but empires very often achieve the step change of effecting rule over vast areas and huge populations by comparatively small numbers of imperial servants.24 For this reason alone, I do not accept that the ancient land empires can have nothing in common with the capitalist sea empires of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries or the American airstrip and aircraft carrier empire of the later twentieth and twenty-first centuries.25 Even a modern account attempting to rehabilitate the reputation of the British Empire reveals telling structural similarities with the themes of this book—the changing realities of any specific empire as it went through phases of (d)evolution, globalization, the shrinking of the world though improved communications and infrastructure, the construction of power around the acquisition of knowledge, resource exploitation as driver or consequence of expansion, and the smoke-and-mirrors realities of minute provincial administrations ruling huge territories and millions of subjects.26

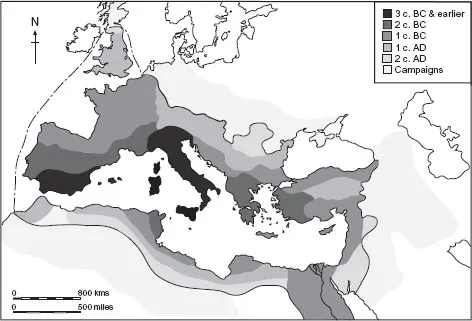

FIGURE 1.1 Map showing phases of expansion of the Roman Empire.

If we consider the extent and chronology of the Roman Empire, along with the manner in which it was acquired and governed, it is apparent that it shares many common characteristics with political and military entities that have been described as empires in world history.27 But it is equally obvious in surveying historical “snapshot” maps of the growth and decline of the Roman territorial empire that this was a dynamic process, with structural breaks and discontinuities, more than a manifest destiny (see figs 1.1–1.2). The sca...