![]()

1

IMAGE AND ECONOMY IN THE ANCIENT WORLD

THE BRONZE AGE OF MIKHAIL ROSTOVTZEFF

Mikhail Ivanovich Rostovtzeff (1870–1952) is remembered most often today for his seminal studies of Greco-Roman antiquity, and for his controversial—some might say untenable—view that the true architects of classical civilization were not those tied to the land, whether as peasant laborers or feudal aristocracy, but rather the middling professional classes of merchants, industrialists, and bankers whose social aspirations were most closely in tune with the civic values of an expanding urban society.1 In reviewing Rostovtzeff’s monumental work on the social and economic history of the Roman Empire, Glenn Bowersock notes that “he presupposed a capitalist society which itself presupposed the primacy of commerce and industry” as guiding influences upon the course of history.2 Rostovtzeff therefore represents one side of an ongoing debate over the nature of economic life in the ancient world, and the extent to which the forms and functions of ancient economies can be understood through the lens of modern experience.3

Rostovtzeff’s life and work has been the subject of several notable studies, written mostly by experts on the classical world.4 This may explain a relative lack of attention to those features of his scholarship that an archaeologist, working on earlier periods, might find most intriguing. They relate less to his championing of the bourgeoisie than to the sheer scale—both spatial and chronological—on which he tried to pursue a complex argument about the relationship between economic forces and cultural change, and also to the variety of historical sources that he brought into account. For Rostovtzeff, the civilizing role of commerce and capital (as opposed to agrarian values and dynastic authority) was not to be reconstructed just on the basis of fiscal records and other textual sources. It could also be detected in the material culture of tribal, nonliterate societies, and most notably in the elaborate styles of imagery that they produced, circulated, and wove together with a consummate skill that still commands our admiration (figure 1.1).

Following on the heels of his (1922) Iranians and Greeks in South Russia, we find a series of lectures on The Animal Style in South Russia and China, delivered at Princeton and published in 1929. I will return to those lectures, and to the subject of China, in chapter 5. The former study laid foundations for an internal account of seminomadic civilization on the Russian steppe, relying mainly on archaeological discoveries, instead of the written accounts of Scythian and Sarmatian culture provided by Greek commentators. Rostovtzeff highlighted the prominence of cosmopolitan display items, procured from urban trading partners, in the tombs of the steppe kings. He took this as evidence that their wealth and power was grounded in access to commercial routes flanking the great patchwork of grasslands between the Danube and the Yellow River. The steppe acted as a kind of cultural cauldron in which otherwise unrelated elements of urban civilization were drawn together in novel combinations, and disseminated farther afield. This was most apparent in the intense fusion of visual styles and techniques to be found in nomadic art, echoes of which could be detected from the northern frontiers of China to Celtic Europe.5

Still more striking are Rostovtzeff’s attempts to find traces of this commercial and cosmopolitan impulse amid the evidence of pre- and protohistoric societies.6 This interest in the deep origins of Old World civilizations becomes more understandable in the context of Rostovtzeff’s exile from his native Russia, at age forty-eight. It provided a way of suggesting that Bolshevik communism, far from being the culmination of a long evolutionary process, was an anomalous departure from the values that had shaped Europe’s development over the millennia.7 Alongside studies of Greco-Roman economy and society, we find Rostovtzeff embroiled in debates over the chronological position and cultural affiliations of Bronze Age metal hoards, unearthed along the shores of the Caspian and Black Seas.8 With remarkable perspicacity, he discerned relationships among the elite iconography of protodynastic Egypt, Mesopotamia, Elam, and the Caucasus, some of which I will be considering in the chapters that follow. And in Iranians and Greeks, we discover a cultural genealogy for the fantastic beasts of Scythian art, reaching back to the first Bronze Age states on the Tigris and Euphrates. The wider implications were fairly clear: feudalism had not emerged from the closed, command economies of Marx’s “Asiatic mode of production,” but from an interconnected world of remote antiquity, bound together by shared commercial interests.

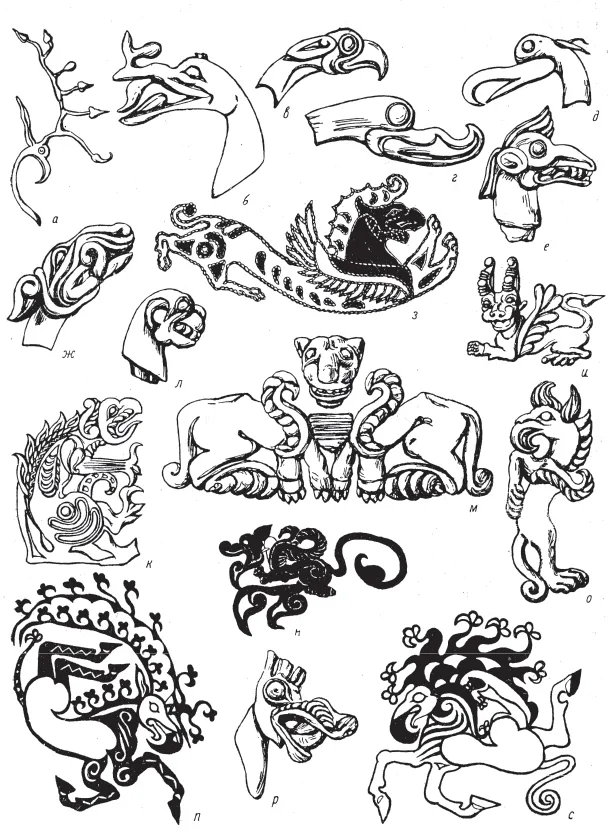

1.1. Images of fantastic creatures from the Pazyryk and Tuekta kurgans, South Russia, seventh to fourth century BC (after S. I. Rudenko. 1960. Kul’tura naseleniia tsentral’nogo Altaia v Skifskoe vremia. Moscow/Leningrad: Izdvo Akademii nauk SSSR, fig. 148).

It is, perhaps, worth trying to relate these prehistoric interests a little more closely to Rostovtzeff’s better-known work on later periods of antiquity. Caravan Cities, published in 1932, was a more personal account of the classical remains at Petra, Jerash, Palmyra, and also Dura-Europos, on the Syrian Euphrates, where Rostovtzeff had excavated. Its opening chapter, tracing the Bronze Age origins of the caravan trade in the Near East, demonstrates an acute awareness of archaeological evidence as a window onto far-flung connections, linking the development of ancient societies. The first great alluvial civilizations of Sumer and Egypt, he noted, were dependent on remote highland sources for supplies of metal, ivory, rare woods, precious stones, spices, cosmetics, pearls, and “incense for the delectation of gods and men.” The archaeological distribution of luxury consumables, commercial instruments, and political symbols confirmed that “the oldest city-states of Sumer in Mesopotamia were linked to far distant lands by caravans: to Egypt in the west, to Asia Minor in the north, to Turkestan, Seistan, and India in the east and south-east.”9

Archaeologists, such as V. Gordon Childe and Henri Frankfort, would later add substance to this historical sketch of a connected Bronze Age world, reaching from the Indus to the Mediterranean, bound together through commerce in rare and precious commodities.10 The chapters that follow will explore that world in greater detail. First, however, there is more to say about Rostovtzeff’s approach to images, and how it defines my own task.

CELEBRATING MONSTERS

By the early decades of the twentieth century, the study of prehistoric and ancient art in continental Europe had become strongly associated with questions of racial identity and national spirit. The influence of Alois Riegl (1858–1905), and his concept of Kunstwollen, was especially strong in Austria and Germany.11 As Jas Elsner points out, the period in which Riegl’s followers developed his new science of the visual arts was also that in which Mendelian genetics were first applied to questions of inheritance and variability among natural species. The common analytical factor, which Elsner also detects in Gestalt psychology, was faith in the idea that minute and critical study of form would eventually lay bare the workings of a grand totality.12

Applied to culture, this paradigm could only incorporate the mixing of local and foreign elements in somewhat ambivalent terms. Hence Riegl, writing of the famous Bronze Age cups from Vapheio near Sparta, could acknowledge a technological debt to Oriental craftsmanship, while insisting that the borrowings had been of a purely technical nature, serving only to augment a preexisting cultural milieu that remained steadfastly Greek, and hence European. Half a century before the decipherment of the Linear B script, which demonstrated the Bronze Age roots of Classical Greek language, he already felt able to write, on the basis of the golden cups and their relief decoration, that “the Mycenaean period heralds the people who would later invent philosophy and the natural sciences and who would create the notion that man is the measure of all things.”13

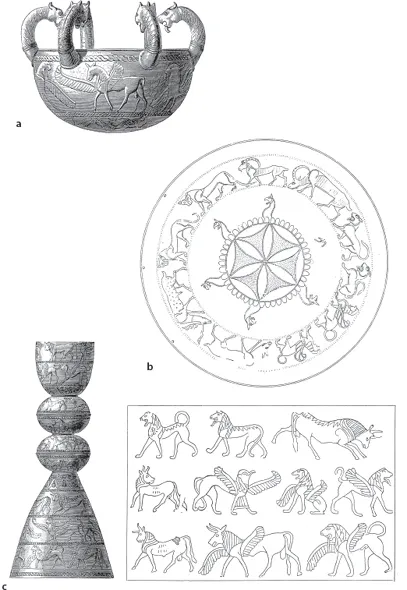

Riegl did not live to see the publication of Fredrik Poulsen’s (1912) study of orientalizing influences upon archaic Greek art. Poulsen’s achievement was to lay out, with unprecedented clarity, a range of evidence for the movement of artistic techniques and motifs—including a variety of composite creatures—from the western fringes of the Neo-Assyrian Empire to the Aegean and central Mediterranean, in the centuries preceding the formation of the classical Greek canon (figure 1.2).14 Perhaps it is wrong to speculate as to whether Riegl would have agreed with the view of some later historians, who interpreted orientalizing art as a kind of unpleasant inoculation, which Greek culture had to endure in order to realize its native genius. But at a time when social fears about a contemporary “Eastern Problem” ran high in Europe, there seemed an obvious significance to the infiltration of Greek art by “monstrous” forces at its point of gestation, and their subsequent “taming” within a native scheme of representation.15

It is against this background that we can begin to appreciate the distinctiveness of Rostovtzeff’s approach to the interpretation of imagery, and his particular attraction to the imaginary creatures of nomadic art. He seems to have delighted in the unbounded character of these particular designs, following their transmission far and wide, across the boundaries of urban and pastoral, literate and nonliterate, societies. In addition to their innately hybrid character—as depictions of fantastic, composite species—the images whose distribution he so carefully traced are also the outcome of cultural admixtures and borrowings, fusing technical knowledge of diverse media and modes of representation from multiple societies. And yet, as he intimated, we typically find these depictions on the surfaces of artifacts that possessed strong local significance as ritual or magical objects, through the use of which each individual society forged its own special relationship to the gods.

1.2. (a, b) Sheet-bronze vessels and (c) stand with relief decoration, engraving, and repoussé, from Central Italy (a, c) and Rhodes (b), seventh century BC (after F. Poulsen. 1912. Der Orient und die frühgriechische Kunst. Leibzig: B. G. Teubner, figs. 86, 135–137).

It might be argued that these movements of monsters, seemingly promiscuous and endlessly adaptive, offered a kind of visual counterpart to Rostovtzeff’s story of an ever-expanding Bronze Age civilization, evolving by virtue of its receptiveness to outside influence, and its ingenuity in weaving together the local and the foreign. As a template for the interpretation of social history, however, this attempt to project Homo economicus onto the world of images—if such it was—was scarcely less idealized than the myths of cultural autochthony that it sought to displace. Image and economy are connected in Rostovtzeff’s work through their distributions in time and space, rather than by any causal or functional relationship. We search in vain for any attempt to account for the fact that, over a period of millennia, the nomadic elite of the Russian steppe not only commissioned and accumulated exotic wealth from an urban hinterland but also sacrificed it to the ground in spectacular burial rites, creating a monumental landscape of kurgan mounds that extended from the Altai to the Black Sea (ensuring, in the process, the physical preservation of objects and images that have largely disappeared from their areas of manufacture).

It is not difficult, with hindsight, to see why Rostovtzeff avoided such matters. In the 1920s and 1930s, they would have brought him into the uneasy company of the Frankfurt- and Vienna-based Kulturkreislehre, or still worse perhaps, the hyper-diffusionist school of prehistory, which was busily tracing the movement of Egyptian cults and esoteric signs across the Atlantic, borne aloft on the slimmest of evidence.16 Yet an unwillingness to consider functional, as opposed to merely distributional, relationships between the spread of representations and the expansion of commerce is equally evident in Rostovtzeff’s reconstructions of later antiquity. Following his gaze around the ruins of Jerash, Petra, or Palymra, it is the ritual landscape of sacred springs and pathways, ornate rock-cut tombs, and stone temples adorned with cult statues that command our attention, but their links to the mundane world of the market, theater, public bath, and household remain unclear.17

What, then, has Rostovtzeff bequeathed to the study of preclassical antiquity that might be of lasting value? Different people will have different answers, but the legacy that interests me, and that I propose to develop, concerns the links he explored between large-scale distributions of images and the growth of commercial an...