![]()

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

WHAT NEEDS TO BE EXPLAINED

THIS BOOK IS AN ECONOMIC history of Europe viewed through the role that energy has played in that history. As such, it also aims to provide an account of the role energy can play in economic history more generally, and how energy consumption and economic development have been, are, and may be, entwined.

All things need energy, and all actions are transformations of energy. Every step, small or large, that a human takes, is part of an energy economy, and every object we treasure, use, or discard is similarly the product of that economy. We have always been “children of the sun,”1 the final source of nearly all of the energy that those living on the surface of this planet will ever consume. The way this energy, with its origins in the nuclear processes at the heart of our nearest star, is obtained and used has put its stamp on human societies since time immemorial, whether of hunter-gatherers, farmers, industrial cities, or astronauts; and whether that energy is consumed as food from plants or animals, as the driving force of wind or water, as the heat of combustion or flow of electricity. All humans that have ever lived have been equally dependent on energy, but each society’s energy economy has taken on distinct forms, and some previous great societal transitions have also been, in their own way, energy revolutions.

But in a very long human history nothing quite like the past couple of hundred years has ever occurred. No previous transformation has been of the scale and intensity of modern times. Indeed, this explosive and ongoing change in scale and speed is what we now evoke with the very word “modern.” While the human population had for the first time advanced to a full billion by the early nineteenth century, less than two hundred years later there are seven times more of us. Yet this sevenfold advance pales beside the increase in our production, which has risen more than seventy-fold in the same period (fifty-five times in the case of Western Europe, the focus of this book). By this measure, the “average” inhabitant of planet Earth is today more than eleven times better off than in 1820, and in Western Europe, eighteen times better off.2 Our technology can achieve feats barely imaginable to our great-great-great grandparents, a mere five generations ago, and each generation continues to be astounded and bewildered by the achievements of the next, even in a world where such change is so commonplace as to have become the norm. Alongside such transformations we are also witnessing a “great acceleration” of impact on our environment, and the possibility that our economy is transgressing the “planetary boundaries” that provide a “safe operating space for humanity,” threatening the functioning of ecosystems and threatening rapid climate change.3 However we value the modern world, it is hard to describe the changes that have occurred without reaching for the lexicon of the big.

Unsurprisingly, a short era that has witnessed more economic growth than in the whole of previous history also has required much more energy. There have been many kinds of revolutions during the modern age. There has been an industrial revolution, or rather three industrial revolutions, which we will use as the organizing principle of the book. There has been an energy revolution or several energy revolutions too, as new energy conversions have been enabled or new energy carriers have been exploited.

We could provide an almost endless list of how radically different our lives have become in the modern, industrial period. Take the case of light. In the premodern world, darkness reigned once the sun slipped below the horizon. Only a handful of cities provided street illumination that cast a weak light into nocturnal streets where only a bright moon provided a guide for the eyes.4 Indoors, most people, if they used artificial light at all, struggled with candles or rush-lights, dried strips of vegetation dipped into animal fat and giving off a foul smell for the short time they burned. How different were the summers and winters then in northern climes, the difference between long, bright nights and short, dim days. Heating was generally provided only when considered an absolute necessity, and then only for one chamber. Even the houses of the well-to-do have well-documented cases of wine freezing in glasses or ink in inkpots. Today manufacturing runs round the clock. Central heating raises temperatures to summer levels in every room irrespective of its use, while for some of us air conditioning seeks to keep the high summer temperatures at bay, out of doors. As centers of population cast their glow into space, we wonder if today’s children will ever see the “true” night sky. By one estimate, the average Briton now consumes six and a half thousand times more artificial light than did their ancestor in 1800.5

The services we get from energy may be the same: heat of low and high temperature, motive power, and light. But in most of Europe in the twenty-first century, none of those services in a domestic home, aside from the work done by the people themselves, are coming from the same sources as they did in the nineteenth century. Not a single one. Such a turnaround has never happened since humans learned to harness fire. And the heat, motion, and light do not just deliver much more of what we used to have, but entirely new services: pictures that come from screens (and can be seen in the dark), voices and music from speakers, conversations in real time that span the globe. This new technology did not just come from changes in knowledge, from the accumulation of generations of ingenuity, but required the use of “energy carriers” that, globally, had only previously been used on a trivial scale and that were inaccessible to most (such as coal, oil, natural gas), or were entirely new (electricity).

As societies and as individuals, our command over resources, and the degree of choice open to us, has vastly increased as a result of these transformations. In a very everyday sense, we have been empowered by the energy revolution; in the choice of what we can do with our time, in our liberation from heavy labor, and in that while we earn much, much, more, we have also benefited from a reduction in working hours since the nineteenth century. This empowerment has come above all in our material life, but in our political and social lives, too. There have also been costs; for many, there may be a sense of disempowerment: a sense of alienation from the natural world that has come with urbanization and the capacity to consume resources with little direct relationship to them. In this book we will stress material changes, but in the broader senses of the word, this is why we think this is a story of bringing power to the people.

Energy also redistributes political power (the more familiar use of “power” to historians). It has not done so in a standard, linear way. Greater energy availability does not, by any means, simply translate into greater democracy or indeed greater governmental control (which are not, in any case, necessarily contradictory). But new systems of harnessing and consuming energy have certainly greatly influenced the options open to governments, individuals, corporations, and countries, and given rise to new areas of contestation and co-operation. Even in the least liberal of European states, people have generally been greatly empowered as consumers relative to their forebears. Sometimes new energy systems have conferred power more directly, whether to the rulers of countries who held major oil reserves, or the political muscle of coalminers, railwaymen and dockers in periods when they populated key parts of the infrastructure.6 The spread of information, whether via steam-powered printing, television, or the Internet, has provided significant new ways to hold leaders to account. Resource endowments have shaped geopolitics.

We can also put numbers to the expansion in energy use: indeed, one of the main contributions of this book is to provide, for the first time, reliable numbers on energy consumption for much of Europe and individual countries within it, including traditional as well as modern energy carriers. The data we can now provide are path-breaking in two regards. First, they provide much more reliable estimates than previously existed on pre–fossil fuel era energy consumption, making much greater use of contemporary sources than pioneering work.7 Second, we have established a consistent methodology for quantifying the economic consumption of energy that can be used for cross-country comparison and aggregation of our datasets.8 These data, focusing on energy as an input into the economy, can then be combined with available long time-series of GDP, capital stocks, and labor to shed new light on what we characterize as “three industrial revolutions” that have occurred over the past two centuries, and their varied impact on energy use in society.

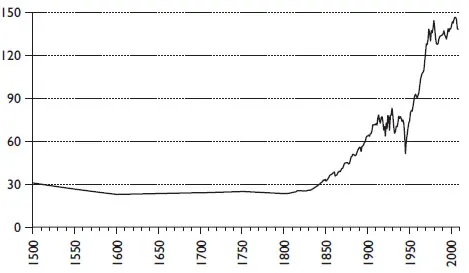

What do these numbers show? We can see in figure 1.1 that the path of the modern economy has not been a straightforward story of a constant rate of increase in the use of energy. Instead, the overall trajectory of energy use within Europe follows a logistic S-shaped curve. It is possible to discern three phases. The first phase, 1500–1800, was marked by little growth in overall energy consumption, and even slightly falling per capita energy consumption in the sixteenth and the eighteenth centuries. The second phase, 1800–1970, is the Industrial Age, which saw explosive expansion in energy use, except for during the World Wars and interwar period. However, industrialization took place at different moments and at different speeds in the countries of Europe, and the curve in figure 1.1, which aggregates the European experience as a whole, makes this change appear smoother than it might seem from a national or regional perspective. The third period, 1970–2008, is exceptional in that it was marked by stabilization in energy consumption per capita. It seems that after around 1970, economic growth has no longer been accompanied by the same level of increase in energy use. Rises in consumption have been modest, and in per capita terms, changed little. At the end of the twentieth century, we seem to have entered a new phase in the relationship between energy and economic growth.

The main thing we set out to explain in this book is why the shape of this curve looks the way it does.

In so doing, we need to investigate the relation between energy and economic growth. This relation is influenced by the kinds of energy carriers involved in the aggregate energy consumption at any point in time. Industrialization has not been just one change in the energy regime, but many: the transition to the first fossil fuel, coal, has been followed by the adoption of oil and natural gas, and the diffusion of electricity. This has affected energy consumption as well as economic growth. For instance, as the main shift into the oil economy happened almost simultaneously across Europe after the Second World War, we see most clearly in the postwar decades, that “golden age” of growth, the explosive increase in energy use that swept the whole continent. Consequently, energy transitions are an important part of our story. Last, but not least, energy transitions influence the economic efficiency of energy use, expressed by the ratio GDP/energy, since different energy carriers form part of new growth complexes, which we call development blocks, using energy to different degrees.

Figure 1.1. Energy consumption per capita in Europe (Gigajoules, 1500–2008)

Sources: Own detailed data, 1800–2008, see www.energyhistory.org. For the period 1500–1800 the trend is nothing more than a rough estimate. See chapter 3.

Of course, bare numbers on energy consumption can only give a bare sense of how everyday life has been transformed, whether through improved access to information, or the much greater ease and speed with which we can accomplish domestic tasks (which means, in turn, that we also do them much more frequently than before, whether washing clothes or heating food and drink at home). Unsurprisingly, ours is a book that stresses material flows and our dependency on physical things. This is not to underplay either changes in, or the role of “wishes, habits, ideas, goals” in this history,9 and these, as they relate to energy, are part of our story (although histories of such things very rarely touch on the role of energy in generating and disseminating them). More energy is not just a consequence of other revolutions, as if it could be hauled up from nothing, like the proverbial man lifting himself by his own bootstraps. We also see the energy revolution as one of the causes of the modern world, and we want to explain why and how this was achieved.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND MAIN ARGUMENTS

At this stage we would like to spell out the main arguments we will make, and the three interrelated research questions we will address, and in doing so position ourselves relative to other approaches:

1. Energy and economic growth;

2. Drivers of energy transitions;

3. Economic efficiency of energy use.

Energy and Economic Growth

The relationship between energy and economic growth is the first and core research question that we deal with throughout the book....