![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The World’s Fairs of 1876 and 1939

On a much-anticipated trip in 1939, a family of four drove from the Philadelphia suburbs up U.S. Route 1 into New Jersey and then turned east through the dark overpasses of Weehawken. Suddenly the road began a sweeping circle to the right, and over the left parapet, lit by the afternoon summer sun, appeared the skyline of Manhattan with the towers of the Empire State and Chrysler buildings and Rockefeller Center. Soon the car descended into the three-year-old Lincoln Tunnel before emerging in New York City itself. The senior author (age twelve) and his brother (age ten) had their first view of New York City on the way to Flushing Meadow, site of the 1939 New York World’s Fair. But first they checked into the Victoria Hotel in Manhattan where they were transferred to somewhere in the sky—probably the thirtieth floor—with a view they had never before experienced. They were in the skyline.

The next morning the family drove to the fair and went to the most popular exhibit, the Futurama ride in the General Motors pavilion, also named Highways and Horizons.1 Although they were early, there was already a line longer than either preteen could see. But they were fresh, and finally their turn came. Into the cushioned seats they nestled, and a smooth voice guided them through an incredible landscape of highways, skyscrapers, parks, cities, factories, and forests, all in miniature and all seen from above as if in a low flying airplane (figures 1.1 and 1.2). The unforgettable sixteen minutes in the grip of Norman Bel Geddes, the industrial designer, surpassed all of the other impressions of the fair. It was the future. Even in youth one could sense the central themes of mobility, speed, and adventure—an urban frontier of new cities and new sceneries. Children of the Depression, the senior author and his brother had traveled very little and had led simple lives; their parents would often point to the impressive stone building in Narberth, Pennsylvania, where they had lost all their savings in the bank crisis. The bank lobby was now a beauty salon.

Figure 1.1. James and David Billington at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Source: Billington family album.

Figure 1.2. The Futurama ride at the 1939 General Motors pavilion. Courtesy of Professor Andrew Wood, San Jose State University, and General Motors.

Those who remember the Futurama ride have lived to see it realized as they circle above any major airport today. There below are the superhighways, the tiny cars, the skyscraper cities, and the vast suburbs. In 1939 this civilization could be glimpsed; a generation later it was reality. Yet the 1939 New York World’s Fair was not just a vision of the future; it portrayed a technology and a society already in existence. The cars, highways, buildings, and industries that Bel Geddes portrayed were familiar objects. The Futurama ride was a celebration of steel and concrete, oil and cars, flight and radio, and above all electric power and light—the great industrial innovations of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Before these transformative changes, America was a mostly rural society. People lived close to nature and prosperity depended on the harvest. Technology was simple: most houses were built out of wood or stone, firewood supplied fuel, candles gave light, and tools and equipment were made of wood and iron. Local transport was by horse or horse-drawn carriage over unpaved roads. Life was slow-paced, and communication—for those who could read and write—was by letter. But the steamboat and then the railroad and the telegraph had begun to reduce isolation and to accelerate the pace of American life. An earlier world’s fair, the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876, celebrated these changes and foreshadowed even greater ones to come.

On May 10, 1876, the “United States International Exhibition” opened in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia. The fair commemorated the one hundredth anniversary of the American Revolution and came to be known as “The Centennial.” Large halls dedicated to horticulture and crafts reflected a nation that was still largely rural and self-sufficient. But the principal attraction of the fair, Machinery Hall, displayed the products of new industries that were beginning to remake society. At the center of Machinery Hall stood the Corliss steam engine, thirty-nine feet high. President Ulysses S. Grant and the visiting Emperor Dom Pedro of Brazil inaugurated the fair by turning on the engine: its two giant pistons turned a huge wheel that powered other machinery in the hall. Built by George Corliss of Providence, Rhode Island, the great engine was the ultimate expression of the steam engineering that had led the first hundred years of America’s industrial growth (figure 1.3).2

The first working steam engine was invented by Thomas Newcomen in 1712. Steam from a separate boiler entered a cylinder on one side of a piston. Applying cold water condensed the steam and created a partial vacuum. Atmospheric pressure on the other side then pushed the piston and pulled a rocking beam, enabling the engine to pump water from mines. In 1769 James Watt created a separate condenser that allowed the temperature of the cylinder to remain relatively constant. Watt’s engine could perform the work of the best Newcomen engines with about one-third of the fuel.

Watt soon designed a version of his engine to turn wheels, providing rotary motion to run factories. Belts connected to the wheels of steam engines soon began turning grain mills, weaving looms, machine tools, and other equipment. Early factories in America did not at first need steam power. Water from nearby rivers gave Francis Lowell and other New England manufacturers the power they needed to create a major new textile industry. By the late nineteenth century, though, many factories had shifted to steam. The Corliss engine on display in Philadelphia was one of the largest rotary steam engines ever built.

Figure 1.3. The Corliss engine at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Fair. Courtesy of the Print and Picture Collection, Philadelphia Free Library. Circulating File.

The greatest contribution of steam was not to drive engines in place but to power mobile engines on boats and trains. The first great American engineering innovation, Robert Fulton’s Clermont steamboat, proved itself in an 1807 trip up the Hudson River from New York to Albany. Steamboats soon opened the Mississippi and Ohio rivers to commerce, creating the world captured by Mark Twain, who began his own career as a steamboat pilot. Ocean going steamships soon carried much larger quantities of goods over long distances. More influential still was the railroad. George and Robert Stephenson of England built locomotives in the 1820s that used steam under high pressure to push pistons directly. During the 1830s and 1840s, railroads and steam locomotives revolutionized transportation in Britain and spread to the United States and other countries. In the 1850s J. Edgar Thomson, chief engineer and later president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, built a rail line across the Allegheny Mountains that brought the U.S. rail network to the Midwest. A transcontinental railway connected the two coasts of the United States in 1869. Locomotives designed by Matthias Baldwin of Philadelphia carried much of nineteenth-century America’s rail traffic and Baldwin locomotives were prominent at the 1876 Centennial (figure 1.4).

But the 1876 fair marked the high point of the reciprocating steam engine and the beginning of its decline, for a new kind of engine made its first public appearance in Philadelphia that summer. Developed by the German engineer Niklaus Otto, the new engine also employed piston strokes. However, instead of burning fuel in a separate boiler to produce steam, Otto’s engine burned fuel directly in a piston cylinder, pushing the piston head in a series of timed combustions. In the 1880s engineers began to use such internal-combustion engines to power automobiles, and in the first two decades of the twentieth century, Henry Ford made an automobile with such an engine that was rugged and cheap enough to reach a mass market. The Ford Model T and other mass-produced cars released transportation from the confines of the rail network and gave a sense of personal freedom to Americans that would define their way of life in the new century.

The Otto engine burned coal gas but internal-combustion engines soon ran on gasoline, a distillate of petroleum. Petroleum refining had grown in the 1850s to supply kerosene, another distillate of crude oil, to indoor lamps for burning as a source of light. Kerosene provided a better illuminant than candles and was more abundant than whale oil. The drilling of underground crude oil deposits in western Pennsylvania in 1859 brought a rush of small drillers and refiners to the region. John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company of Cleveland, Ohio, soon dominated the industry, growing from a local refiner in 1870 into a national monopoly a decade later. Standard Oil’s market for kerosene gradually declined as electric power spread and made indoor electric lights an alternative to kerosene. But the automobile would give the oil refining industry a new and even greater market in the twentieth century.

The year of the Centennial was the year Thomas Edison set up his research laboratory at Menlo Park, New Jersey. His greatest inventions were still in the future: the phonograph (1877), the carbon telephone transmitter (1877), an efficient incandescent light (1879), and the electric power network to supply it (1882). But by 1876 Edison had established a reputation as an inventor through improvements he had made to the electric telegraph. Developed in the 1830s and 1840s by Samuel F. B. Morse, the telegraph revolutionized communications in the nineteenth century. One company, Western Union, dominated long-distance telegraphy by the 1870s. The Philadelphia Centennial fair had its own telegraph office, and telegraph devices, lines, and poles were on display. Yet the Centennial marked the high point of the telegraph too, for it was at the Philadelphia fair that Alexander Graham Bell gave his first public demonstration of a telephone. With the telegraph, messages had to be sent and received in offices by trained operators and then delivered by messengers. The telephone permitted instant two-way communication by voice. Bell’s company eventually replaced Western Union as the telecommunications giant of the United States, and daily life in the twentieth century would come to depend on the telephone as much as on the car.

Figure 1.4. Baldwin locomotive at the Centennial Fair. Courtesy of the Print and Picture Collection, Philadelphia Free Library. No. II-1342.

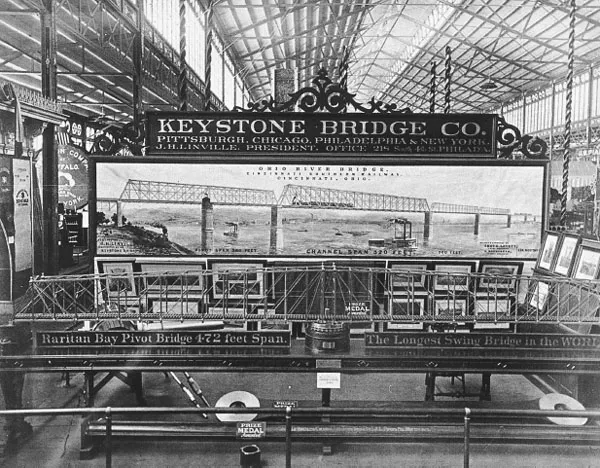

Like Edison, Andrew Carnegie was a telegraph operator early in his career. Carnegie rose in the 1850s from telegrapher in the Pittsburgh office of the Pennsylvania Railroad to manager of the office himself. Striking out on his own, he left the railroad in 1865 to form the Keystone Bridge Company, which built bridges across the Ohio and other rivers. Models of Keystone bridges were on display at the Centennial (figure 1.5). The enormous market for steel soon induced Carnegie to manufacture it, and he built the world’s largest steel plant near Pittsburgh in 1875. He sold his firm to the New York banker J. P. Morgan in 1901, who merged it with rivals to create the first great twentieth-century corporation, United States Steel. Steel made possible the tall skyscraper buildings and long-span bridges that reshaped the cities and landscape of the twentieth century.

These breakthroughs were not the only technically significant events of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But the telephone, the electric power network, oil refining, the automobile and the airplane, radio, and new structures in steel and concrete were the innovations that set the twentieth century apart from the nineteenth. Some of these innovations and the individuals who conceived them are more familiar than others: most Americans have heard of Bell and the telephone but few will have heard of Othmar Ammann, whose George Washington Bridge connected New York to New Jersey in 1931 and became the model for large suspension bridges. This book describes these innovators and their work.

The book also explains innovations in engineering terms. Modern engineering can be grouped into four basic kinds of works: structures, machines, networks, and processes. A structure is an object, like a bridge or a building, that works by standing still. A machine is an object, such as a car, that works by moving or by having parts that move. A network is a system that operates by transmission, in which something that begins at one end is received with minimal loss at the other end (e.g., the telephone system). Finally, a process operates by transmutation, in which something that enters one end is changed into something different at the other end (e.g., oil refining). We will see that many innovations are combinations of these four ideas. With structure, machine, network, and process as a basic vocabulary, complex objects and systems can be understood in terms of their essential features.

Figure 1.5. Keystone Bridge Company exhibit at the Centennial Fair. Courtesy of the Print and Picture Collection, Philadelphia Free Library. No. III-2339.

Engineers describe their works with numbers, and certain numerical relationships or formulas characterize the key engineering works of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These formulas do not explain any object or system in detail; professional engineers today would use more complex mathematics to analyze and design things. But the formulas in this book each convey the basic idea of a key work and enable the reader to think about great works of technology as engineers would think about them. In this way, the reader can enter into the imagination of the designers and can understand the basic choices that went into a design.

The Model T automobile of 1908 is an example. The car’s engine had four cylinders, each containing a piston attached to a single crankshaft underneath the engine. In a timed sequence, gasoline entered each cylinder for ignition and the combustion pushed each piston downward and turned the crankshaft. Another shaft running the length of the car transmitted the rotary motion to the axles and the wheels. A simple relationship expressed by the formula PLAN/33,000 represents this activity and gives the indicated horsepower of the engine. Combustion creates a pressure P (in pounds per square inch) on the head of the piston in each cylinder. The piston travels down the length L of the cylinder (in feet). The area of the piston head A (in square inches) and the number of power strokes per minute N provide other essential information, and dividing by 33,000 gives the indicated horsepower. The formula expresses the basic working of the car’s engine. In chapter 5, we give the PLAN numbers for the Model T and explain how the car was efficient for the needs and conditions of the time.

A suspension bridge has no moving parts but can be explained by a formula that relates its weight and size. A suspension bridge typically has two towers that carry a roadway de...