![]()

PART 1

Modeling

![]()

Chapter One

Introduction

The essence of the individual-based approach is the derivation of the properties of ecological systems from the properties of the individuals constituting these systems.

—Adam Łomnicki, 1992

1.1 WHY INDIVIDUAL-BASED MODELING AND ECOLOGY?

Modeling attempts to capture the essence of a system well enough to address specific questions about the system. If the systems we deal with in ecology are populations, communities, and ecosystems, then why should ecological models be based on individuals? One obvious reason is that individuals are the building blocks of ecological systems. The properties and behavior of individuals determine the properties of the systems they compose. But this reason is not sufficient by itself. In physics, the properties of atoms and the way they interact with each other determine the properties of matter, yet most physics questions can be addressed without referring explicitly to atoms.

What is different in ecology? The answer is that in ecology, the individuals are not atoms but living organisms. Individual organisms have properties an atom does not have. Individuals grow and develop, changing in many ways over their life cycle. Individuals reproduce and die, typically persisting for much less time than the systems to which they belong. Because individuals need resources, they modify their environment. Individuals differ from each other, even within the same species and age, so each interacts with its environment in unique ways. Most important, individuals are adaptive: all that an individual does—grow, develop, acquire resources, reproduce, interact—depends on its internal and external environments. Individual organisms are adaptive because, in contrast to atoms, organisms have an objective, which is the great master plan of life: they must seek fitness, that is, attempt to pass their genes on to future generations. As products of evolution, individuals have traits allowing them to adapt to changes in themselves and their environment in ways that increase fitness.

Fitness-seeking adaptation occurs at the individual level, not (as far as we know) at higher levels. For example, individuals do not adapt their behavior with the objective of maximizing the persistence of their population. But, as ecologists, we are interested in such population-level properties as persistence, resilience, and patterns of abundance over space and time. None of these properties is just the sum of the properties of individuals. Instead, population-level properties emerge from the interactions of adaptive individuals with each other and with their environment. Each individual not only adapts to its physical and biotic environment but also makes up part of the biotic environment of other individuals. This circular causality created by adaptive behavior gives rise to emergent properties.

If individuals were not adaptive, or were all the same, or always did the same thing, ecological systems would be much simpler and easier to model. However, such systems would probably never persist for much longer than the lifetime of individuals, much less be resilient or develop distinctive patterns in space and time. Consider, for example, a population in which individuals are all the same, have the same rate of resource intake, and all reproduce at the same time. The logical consequence of this scenario (Uchmański and Grimm 1996) is that, of course, the population will grow exponentially until all resources are consumed and then cease to exist. Or consider a fish school as an example system with emergent properties (Huth and Wissel 1992, 1994; Camazine et al. 2001; section 6.2). The school’s properties emerge from how individual fish move with respect to neighboring individuals. If the fish suddenly stopped adjusting to the movement of their neighbors, the school would immediately lose its coherence and cease to exist as a system.

Now, if ecologists are interested in system properties, and these properties emerge from adaptive behavior of individuals, then it becomes clear that understanding the relationship between emergent system properties and adaptive traits of individuals is fundamental to ecology (Levin 1999). Understanding this relationship is the very theme underlying our entire book: how we can use individual-based models (IBMs) to determine the interrelationships between individual traits and system dynamics?

But can we really understand the emergence of system-level properties? Ecological systems are, after all, complex. Even a population of conspecifics is complex because it consists of a multitude of autonomous, adaptive individuals. Communities and ecosystems are even more complex. If an IBM is complex enough to capture the essence of a natural system, is the IBM not as hard to understand as the real system? The answer is no—if we have an appropriate research program. But before we outline this program, which we refer to as “individual-based ecology,” let us first look at three successful uses of individual-based models. Although these examples (which are described in more detail in chapter 6) address completely different systems and questions, they have common elements that play an important role in individual-based ecology.

1.2 LINKING INDIVIDUAL TRAITS AND SYSTEM COMPLEXITY: THREE EXAMPLES

1.2.1 The Green Woodhoopoe Model

The green woodhoopoe (Phoeniculus purpureus) is a socially breeding bird of Africa (du Plessis 1992). The social groups live in territories where only the alpha couple reproduces. The subdominant birds, the “helpers,” have two ways to achieve alpha status. Either they wait until they move up to the top of the group’s social hierarchy, which may take years, or they undertake scouting forays beyond the borders of their territories to find free territories. Scouting forays are risky because predation, mainly due to raptors, is considerably higher while on a foray. Now the question is: how does a helper decide whether to undertake a scouting foray? We cannot ask the birds how they decide, of course, and we do not have enough data on individual birds and their decisions to answer these questions empirically.

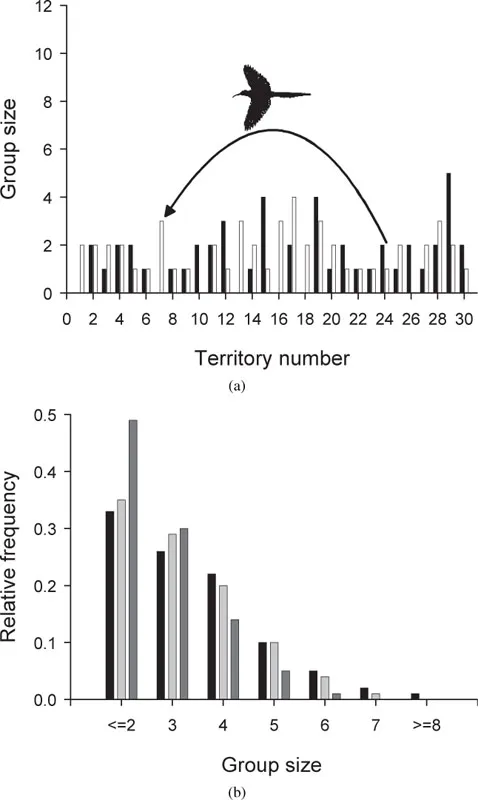

What we have, however, is a field study that compiled a group size distribution over more than ten years (du Plessis 1992). We can thus develop an IBM and test alternative theories of helper decisions by how well the theories reproduce the observed group size distribution (Neuert et al. 1995). These theories represent the internal model used by the birds themselves for seeking fitness. It turned out that a heuristic theory of the helpers’ decisions, which takes into account age and social rank, caused the IBM to reproduce the group size distribution at the population level quite well (figure 1.1), whereas alternative theories assuming nonadaptive decisions (e.g. random decisions) did not. Then, after a sufficiently realistic theory of individual behavior was identified, questions addressing the population level could be asked—for example, on the significance of scouting distance to the spatial coherence of the population. It turned out that even very small basic propensities to undertake long-ranging scouting forays allow a continuous spatial distribution to emerge, whereas if the helpers only search for free alpha positions in neighboring territories the population falls apart (section 6.3.1; figure 6.5).

1.2.2 The Beech Forest Model

Without humans, large areas of Middle Europe would be covered by forests dominated by beech (Fagus silvatica). Foresters and conservation biologists are therefore keen to establish forests reserves that restore the spatiotemporal dynamics of natural beech forests and to modify silviculture to at least partly restore natural structures. But how large should such protected forests be? And how long would it take to reestablish natural spatiotemporal dynamics? What forces drive these dynamics? What would be practical indicators of naturalness in forest reserves and managed forests? Because of the large spatial and temporal scales involved, modeling is the only way to answer these questions. But how can we find a model structure that is simple enough to be practical while having the resolution to capture essential structures and processes?

Figure 1.1 Individual decisions and population-level phenomena in the woodhoopoe IBM of Neuert et al. (1995). (a) Group size (black: male; white: female) in thirty linearly arranged territories. Subdominants decide whether to undertake long-distance scouting forays to find vacant alpha positions. (b) Observed group size distribution (black), and predicted distributions for the reference model (scouting decisions based on age and social rank; light gray); and a model with scouting decisions independent of age and status (dark gray). (After Neuert et al. 1995.)

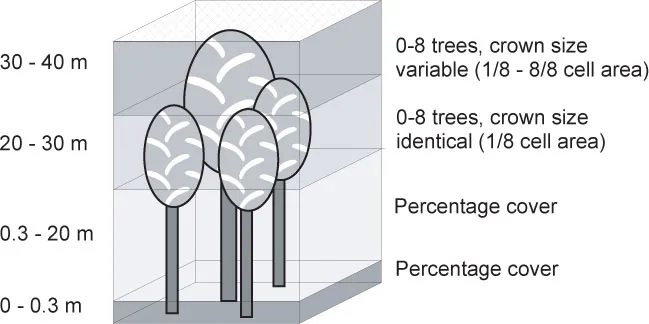

What we can do to find the right resolution of the model is use patterns observed at the system level. For example, old-growth beech forests show a mosaic pattern of stands in different developmental phases (Remmert 1991; Wissel 1992a). The model must therefore be spatially explicit with resolution fine enough for the mosaic pattern to emerge. Another pattern is the characteristic vertical structures of the developmental stages (Leibundgut 1993; Korpel 1995). For example, the “optimal stage” is characterized by a closed canopy layer and almost no understory. The model thus has to have a vertical spatial dimension so that vertical structures can emerge (figure 1.2). Within this framework the behavior of individual trees can be described by empirical rules because foresters know quite well how individual growth and mortality depend on the local environment of a tree. Likewise, empirical information is available to define rules for the interaction of individuals in neighboring spatial units.

The model BEFORE (Neuert 1999; Neuert et al. 2001; Rademacher et al. 2001, 2004; section 6.8.3), which was constructed in this way, reproduced the mosaic and vertical patterns. It was so rich in structure and mechanism that it also produced independent predictions regarding aspects of the forest not considered at all during model development and testing. These predictions were about the age structure of the canopy, spatial aspects of this age structure, and the spatial distribution of very old and large trees. All these predictions were in good agreement with observations, considerably increasing the model’s credibility. The use of multiple patterns to design the model obviously led to a model that was structurally realistic. This realism allowed the addition of model rules to track woody debris, which was not an original objective of the model. Again, the amount and spatial distribution of coarse woody debris in the model forest were in good agreement with observations in natural forest and old forest reserves (Rademacher & Winter 2003). Moreover, by analyzing hypothetical scenarios where, for example, no windfall occurred, it could be shown that storms and windfall have both desynchronizing (at larger scales) and synchronizing (at the local scale) effects on the spatiotemporal dynamics of beech forests. The model thus can be used for answering both applied (conservation, silviculture) and theoretical questions.

Figure 1.2 Vertical structure of the beech forest model BEFORE (Neuert 1999; Rademacher et al. 2001). (Modified from Rademacher et al. 2001.)

1.2.3 The Stream Trout Model

Models have been used to assess the effects of alternative river flow regimes on fish populations at hundreds of dams and water diversions. However, the approach most commonly used for this application, habitat selection modeling, has important limitations (Garshelis 2000; Railsback, Stauffer, and Harvey 2003). IBMs of stream fish have been developed as an alternative to habitat selection modeling (e.g., Van Winkle et al. 1998). These IBMs attempt to capture the important processes determining survival, growth, and reproduction of individual fish, and how these processes are affected by river flow. The trout literature, for example, shows that mortality risks and growth are nonlinear functions of habitat variables (depth, velocity, turbidity, etc.) and fish state (especially size), and that competition among trout resembles a size-based dominance hierarchy. River fish rapidly adapt to changes in habitat and competitive conditions by moving to different habitat, so modeling this adaptive behavior realistically is essential to understanding flow effects.

However, existing foraging theory could not explain the ability of trout to make good trade-offs between growth and risk in selecting habitat under a wide range of conditions. A new theory was developed from the assumption that fish select habitat to maximize the most basic element of fitness, the probability of surviving over a future period (Railsback et al. 1999). This survival probability considers both food intake and predation risk: if food intake is insufficient, the individual will starve over the future period, but if it feeds without regard for risk, it will likely be eaten. The new theory was tested by demonstrating that it could reproduce, in a trout IBM, a wide range of habitat selection patterns observed in real trout populations (Railsback and Harvey 2002).

Once its theory for how trout select habitat was tested, the IBM’s ability to reproduce and explain population-level complexities was analyzed (Railsback et al. 2002). The IBM was found to reproduce system-level patterns observed in real trout including self-thinning relationships, “critical periods” of intense density-dependent mortality among juveniles, density-dependence in juvenile size, and effects of habitat complexity on population age structure. Further, the IBM suggested alternatives to the conventional theory behind these patterns (section 6.4.2).

In an example management application, the trout IBM was used to predict the population-level consequences of stream turbidity (Harvey and Railsback 2004). Individual-level laboratory studies have shown that turbidity (cloudiness of the water) reduces both food intake and predation risk. Whereas the population-level consequences of these two offsetting individual-level effects would be very difficult to evaluate empirically, they can be easily predicted using the IBM: over a wide range of parameter values, the negative effects of turbidity on growth outweighed the positive effects on risk.

1.3 INDIVIDUAL-BASED ECOLOGY

The preceding examples address different systems and problems, and the models differ considerably in structure and complexity. What they have in common, however, is the general method of formulating theories about the adaptive behavior of individuals and testing the theories by seeing how well they reproduce, in an IBM, patterns observed at the system level. The main focus may be more on the adaptive behavior of individuals, as in the woodhoopoe and stream trout examples, or on system-level properties, as in the beech forest example, but the general method of developing and using IBMs is the same.

This general method of using IBMs is a distinctly different way of thinking about ecology. We therefore have taken the risk of coining a new term, individual-based ecology (IBE), for the approach to studying and modeling ecological systems that this book is about. Classical theoretical ecology, which still has a profound effect on the practice of ecology, usually ignores individuals and their adaptive behavior. In contrast, in IBE higher organizational levels (populations, communities, ecosystems) are viewed as complex systems with properties that arise from the traits and interactions of their lower-level components. Instead of thinking about populations that have birth and death rates that depend only on population size, with IBE we think of systems of individuals whose growth, reproduction, and death is the outcome of adaptive behavior. Instead of going in the field and only observing population density in various kinds of habitat, with IBE we also study the processes by which survival and growth of individuals are affected by habitat (and by other individuals) and how the individuals adapt.

The following are important characteristics of IBE. Many of these have more similarity to interdisciplinary complexity science (e.g., Auyang 1998; Axelrod 1997; Holland 1995, 1998) than to traditional ecology:

1. Systems are understood and modeled as collections of unique individuals. System properties and dynamics arise from the interactions of individuals with their environment and with each other.

2. Individual-based modeling is a primary tool for IBE because it allows us to study the relationship between adaptive beh...