![]()

PART I

Some are born great

![]()

The oracle neither conceals, nor reveals, but indicates.

—Heraclitus in Plutarch, Moralia 404D

I

ORACLE

The appointed day had come. Having journeyed up the winding mountain paths to the sanctuary hidden within the folds of the Parnassian mountains, individuals from near and far, representatives from cities and states, dynasties and kingdoms across the Mediterranean had gathered in Apollo’s sanctuary. As dawn broke, the word spread that it would soon be known whether the god Apollo was willing to respond to their questions. Sunlight reflected off the temple’s marble frontage, the oracular priestess entered its inner sanctum, and the crowd of consultants moved forward, waiting their turn to know better what the gods had in store. The gods were considered all powerful, all controlling, and all knowing; their decisions, time and again, had proven to be final. The consultants had waited perhaps months, traveled perhaps thousands of miles. Now they waited patiently for their turn, each likely entering the home of the god with a great deal of trepidation as to what he might be told. Some left content. Others disappointed. Most thoughtful. With dusk, the god’s priestess fell silent. The crowds dispersed, heading to every corner of the ancient world, bringing with them the prophetic words of the oracle at Delphi.

Without doubt, what fascinates us most about Delphi are the stories surrounding its oracle and the women who, for centuries, acted as the priestesses and mouthpieces of the god Apollo at the center of a Delphic oracular consultation (see fig. 1.1). But just how did the oracle at Delphi work, and why did it work for the ancient Greek world for so long?

Figure 1.1. Tondo of an Athenian red-figure cup c. 440–30 BC, found in Vulci, Etruria, showing Aegeus consulting Themis/the Pythia (© Bildarchiv Preussicher Kulturbesitz [Staatliche Museum, Berlin])

These are difficult questions to answer for two central reasons. First, because, incredibly for an institution so central to the Greek world for so long, there has survived no straightforward, complete account about exactly how a consultation with the oracle at Delphi took place, or about how the process of bestowing divine inspiration upon the Pythian priestess worked. Of the sources we have, those from the classical period (sixth through fourth centuries BC) treat the process of consultation as common knowledge, to the extent that it does not need explaining, and indeed the consultations at Delphi often act as shorthand for descriptions of other oracular sanctuaries (“it happens here just like at Delphi …”). Many of the sources interested in discussing how the oracle worked in any detail are actually from Roman times (first century BC to fourth century AD), and thus at best can tell us only what the people in this later period thought (and often they offer conflicting stories) about a process that, as all of those writers agreed, was by then past its heyday. Also, while the archaeological evidence is of some use both in helping us understand the environment in which the consultation took place and in revealing possible scenarios about the process by which the Pythia was inspired during the classical, Hellenistic, and Roman periods, it comes up short in helping us understand the first centuries of the oracle’s existence (the late eighth and seventh centuries BC), during which the oracle was, according to the literary sources, astoundingly active.1

The second difficulty surrounding the oracle is in analyzing the literary evidence for what questions were put to her and the responses she gave.2 This is not only because many of the responses are recorded for us by ancient authors writing long after the response was supposedly uttered, and sometimes by those hostile to pagan religious practices, like the Christian writer Eusebius. And it is not only because these writers themselves often were relying on other sources for their information, with the result that even if two or more describe the same oracular consultation, their records of it are often different. It is also because these writers tend not to record oracular consultations as “straight” history, but rather employ these stories to perform a particular function within their own narratives.3 As a result, some scholars have sought to label as ahistorical nearly everything the oracle from Delphi is said to have pronounced before the fifth century BC. Others have thought it almost impossible to write a history of the Delphic oracle after the fourth century BC because of difficulties with the sources. Still others have tried to steer a middle path in a spectrum of more likely to less likely, albeit with the understanding, as the scholars Herbert Parke and Donald Wormell put it in their still-authoritative catalog of Delphic oracular responses in 1956, that “there are thus practically no oracles to which we can point with complete confidence in their authenticity.”4

As several scholars have remarked, it is thus one of Delphi’s many ironies that the Pythian priestesses—the women central to a process that was supposed to give clarity to difficult decisions in the ancient world—have taken the secret of that process to their graves and left us instead with such an opaque view of this crucial ancient institution. In such a situation, the only option is to produce a fairly static snapshot of what we know was a changing oracular process at Delphi over its more than one thousand–year history; a snapshot that is both a compilation of sources from different times and places (with all the accompanying difficulties such an account brings) and one that inevitably takes a particular stance on a number of conflicting and unresolvable issues.

The oracle at Delphi was a priestess, known as the Pythia. We know relatively little about individual Pythias, or about how and why they were chosen.5 Most of our information comes from Plutarch, a Greek writing in the first century AD, who came from a city not far from Delphi and served as one of the priests in the temple of Apollo (there was an oracular Pythian priestess at the temple of Apollo, but also priests—more on the latter later). The Pythia had to be a Delphian, and Plutarch tells us that in his day the woman was chosen from one of the “soundest and most respected families to be found in Delphi.” Yet this did not mean a noble family; in fact, Plutarch’s Pythia had “always led an irreproachable life, although, having been brought up in the homes of poor peasants, when she fulfils her prophetic role she does so quite artlessly and without any special knowledge or talent.”6 Once chosen, the Pythia served Apollo for life and committed herself to strenuous exercise and chastity. At some point in the oracle’s history, possibly by the fourth century BC and certainly by AD 100, she was given a house to live in, which was paid for by the sanctuary. Plutarch laments that while in previous centuries the sanctuary was so busy that they had to use three Pythias at any one time (two regular and one understudy), in his day one Pythia was enough to cope with the dwindling number of consultants.7

Diodorus Siculus (Diodorus “of Sicily”), who lived in the first century BC, tells us that originally the woman picked had also to be a young virgin. But this changed with Echecrates of Thessaly, who, coming to consult the Pythia, fell in love with her, carried her off, and raped her; thus the Delphians decreed that in the future the Pythia should be a woman of fifty years or older, but that she should continue, as Pythia, to wear the dress of a maiden in memory of the original virgin prophetess. Thus, it is thought not uncommon for women to have been married and to have been mothers before being selected as the Pythia, and, as a result, withdrawing from husbands and families to perform their role.8

The Pythia was available for consultation only one day per month, thought to be the seventh day of each month because the seventh day of the month of Bysios—the beginning of spring (our March/April)—was considered Apollo’s birthday. Moreover, she was only available nine months of the year, since during the three winter months Apollo was considered absent from Delphi, and instead living with the Hyperboreans (a mythical people who lived at the very edges of the world). During this time, Delphi may have been oracle-less but was not god-less; instead the god Dionysus was thought to rule the sanctuary.9

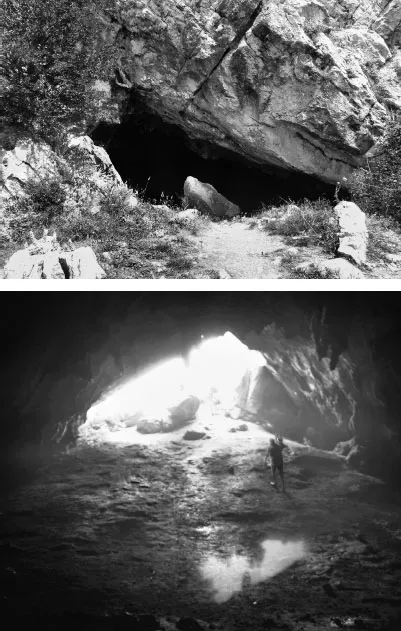

Despite this rather narrow window of opportunity for consultation—only nine days per year—there has been much discussion of the availability (and, indeed, popularity) of alternative forms of divination on offer at Delphi. In particular, scholars have debated the existence of a “lot” oracle: a system whereby a sanctuary official, perhaps the Pythia, would perform a consultation using a set of randomized (“lottery”) objects, which would be “read” to give a response to a particular question.10 Such a system of alternative consultation may also have been supplemented by a “dice” oracle performed at the Corycian cave high above Delphi (see figs. 0.2, 1.2), which from the sixth century BC onward, was an increasingly popular cult location for the god Pan and the Muses, and a firmly linked part of the “Delphic” itinerary and landscape.11

On the nine days a year set aside for full oracular consultation, the day seems to have progressed as follows. The Pythia would head at dawn to bathe in the Castalian spring near the sanctuary (see fig. 0.2). Once purified, she would return to the sanctuary, probably accompanied by her retinue, and enter into the temple, where she would burn an offering of laurel leaves and barley meal to Apollo, possibly accompanied by a spoken homage to all the local deities (akin to that dramatized in the opening scene of the ancient Greek tragedy Eumenides by the playwright Aeschylus).12 Around the same time, however, the priests of the temple were responsible for verifying that even these rare days of consultation could go ahead. The procedure was to sprinkle cold water on a goat (which itself had to be pure and without defect), probably at the sacred hearth within the temple. If the goat shuddered, it indicated that Apollo was happy to be consulted. The goat would then be sacrificed on the great altar to Apollo outside the temple as a sign to all that the day was auspicious and the consultation would go ahead.13

Figure 1.2. The Corycian cave from the outside (top) and inside (bottom), high above Delphi on a plateau of the Parnassian mountains (© Michael Scott)

The consultants, who would have had to arrive probably some days before the appointed consultation day, would now play their part. They first had to purify themselves with water from the springs of Delphi. Next, they had to organize themselves according to the strict rules governing the order of consultation. Local Delphians always had first rights of audience. What followed them was a system of queuing that prioritized first Greeks whose city or tribe was part of Delphi’s supreme governing council (called the Amphictyony), then all other Greeks, and finally non-Greeks. But within each “section” (e.g., Amphictyonic Greeks), there was also a way to skip to the front, a system known as promanteia. Promanteia, the right “to consult the oracle [manteion] before [pro] others,” could be awarded to individuals or cities by the city of Delphi as an expression of the close relationship between them or as thanks for particular actions. Most famously, the island of Chios was awarded promanteia following its dedication of a new giant altar in the Apollo sanctuary (see fig. 1.3), on which they later inscribed, in a rather public way given that the queue very likely went past their altar, the fact that they had been awarded promanteia. If there were several consultants with promanteia within a particular section, their order was decided by lot, as was the order for everyone else within a particular section.14

Figure 1.3. A reconstruction of the temple terrace, the area in front of the temple of Apollo in the Apollo sanctuary of Delphi, with main structures marked (© Michael Scott) 1 Delphi charioteer. 2 Fourth century BC column with omphalos and tripod. 3 Stoa of Attalus. 4 Apollo temple. 5 Athenian palm tree dedication. 6 Statue and columns of Sicilian rulers. 7 Column and statue of Aemilius Paullus. 8 Altar of Chians. 9 Salamis Apollo. 10 Rhodian statue of Helios. 11 Statues of Attalus II and Eumenes II of Pergamon. 12 Direction of approach for those coming from lower half of Apollo sanctuary. 13 Plataean serpent column.

Once the order was decided, the money had to be paid. Each consultant had to offer the pelanos, literally a small sacrificial cake that was burned on the altar, but that they had to buy from the Delphians for an additional amount (the “price” of consultation, and the source of a regular and bountiful income for Delphi). We don’t know a lot about the prices charged, except that they varied. One inscription, which has survived to us, recounts an agreement between Delphi and Phaselis, a city in Asia Minor, in 402 BC. The price for a “state” inquiry (i.e., by the city) was seven Aeginetan drachmas and two obols. The price for a “private” inquiry by individual Phaselites was four obols.15 The interesting points here are not only the difference in price for offici...