![]()

1

Emerging Markets Crises and Policy Responses

Many excellent books and articles have documented the new breed of “twenty-first century” financial crises.1 I will therefore content myself with a short overview of the main developments. This chapter can be skipped by readers who are familiar with Emerging Markets (EM) crises.

The pre-crisis period

No two crises are identical. At best we can identify a set of features common to most if not all episodes. Let us begin with a list of frequent sources of vulnerability in recent capital-account crises.

Size and nature of capital inflows. The new breed of crises was preceded by financial liberalization and very large capital inflows. In particular the removal of controls on capital outflows (the predominant form of capital control) has led to massive and rapid inflows of capital. Instead of inducing onshore capital to flow offshore to earn higher returns, these removals have enhanced the appeal of borrowing countries to foreign investors by signaling the governments’ willingness to keep the doors unlocked.2

At the aggregate level, the net capital flows to developing countries exceeded $240 bn in 1996 ($265 bn if South Korea is included), six times the number at the beginning of the decade, and four times the peak reached during the 1978–82 commercial lending boom.3 Capital inflows represented a substantial fraction of gross domestic product (GDP) in a number of countries: 9.4 percent for Brazil (1992–5), 25.8 percent for Chile (1989–95), 9.3 percent in Korea (1991–5), 45.8 percent in Malaysia (1989–95), 27.1 percent in Mexico (1989–94) and 51.5 percent in Thailand (1988–95).4

This growth in foreign investment has been accompanied by a shift in its nature, a shift in lender composition, and a shift in recipients. Before the 1980s, medium-term loans issued by syndicates of commercial banks to sovereign states and public sector entities accounted for a large share of private capital flows to developing countries, and official flows to these countries were commensurate with private flows.

Today private capital flows dwarf official flows. On the recipient side,5 borrowing by the public sector has shrunk to less than one-fifth of total private flows.6 As for the composition of private flows, the share of foreign direct investment (FDI) has grown from 15 percent in 1990 to 40 percent, and that of global portfolio bond and equity flows grew from a negligible level at the beginning of the decade to about 33 percent in 1997. Bank lending has evolved toward short-term, foreign currency denominated debt. Such foreign bank debt, mostly denominated in dollars and with maturity under a year, reached 45 percent of GDP in Thailand, 35 percent in Indonesia and 25 percent in Korea just before the Asian crisis.7

There are several reasons for the sharp increase in the capital flows in the last twenty years:8 the ideological shift to free markets and the privatizations in developing countries; the arrival of supporting infrastructure such as telecommunications and international standards on banking supervision and accounting; the regulatory changes that made it possible for the pension funds, banks, mutual funds, and insurance companies of developed countries to invest abroad; the perception of new, high-yield investment opportunities in Emerging-Market economies; and the new expertise associated with the development of the Brady bond market.9

Banking fragility. Up to the 1970s, balance of payment crises were largely unrelated to bank failures. The banking industry was highly regulated, and banking activity was much more limited and far less risky than it is now. It operated mostly at the national level and foreign borrowings were strictly constrained by exchange controls. Various regulations, such as licensing restrictions and interest rate ceilings, kept banks from competing against each other. There were also far fewer financial markets and derivative instruments to play with.

The 1970s and 1980s witnessed a trend toward openness and deregulation, but the subsequent expansion in banking activities and exposure in capital markets made banking riskier. In response, the Basle Committee on Banking Supervision in the past several years has been involved in instituting new banking regulations, concerning minimum capital standards for credit risk (the Basle Accord in 1988), and risk management (the 1996 Amendment to the Accord to account for market risk on the banks’ trading book), and is proposing some further reforms.

A common feature of the new breed of crises is the fragility of the banking system prior to the crisis.10 Often, the relaxation of controls on foreign borrowing took place without adequate supervision. For example, banking problems played a central role in the Latin American crises of the early 1980s.11 The widespread insolvency of Chilean institutions in 1981–4 resulted in the Chilean government guaranteeing all foreign debts of the Chilean banking system and owning 70 percent of the banking system in 1985. Similarly, the banks of the East Asian countries that suffered crises in 1997 (Thailand, Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia) were very poorly capitalized. [More generally, overleverage was not confined to banks as firms’ balance sheets also deteriorated prior to the crises. For example, leverage doubled in Malaysia and Thailand between 1991 and 1996, according to the World Bank (1997).]

Currency and maturity mismatch. Some of the domestic debt and virtually all of the external debt of EM economies is denominated in foreign currency, with very little hedging of exchange rate risk, a phenomenon labeled “liability dollarization” by Calvo (1998). For example, before the Asian Crisis, Thailand, Korea, and Indonesia created incentives to borrow abroad through implicit and explicit guarantees and other policy-induced incentives.12 To be certain, banking regulations usually mandate currency matching, but such regulations have often been weakly enforced. Furthermore, even if the banks’ books are formally matched, they may be subject to a substantial foreign exchange risk through their non-bank borrowers’ risk of default. For example, the Indonesian private sector engaged heavily in liability dollarization, and so the banks faced an important “credit risk” (de facto a foreign exchange risk) with those borrowers who had borrowed in foreign currencies.

The second type of mismatch was on the maturity side. For instance, 60 percent of the $380 bn of international bank debt outstanding in Asia at the end of 1997 had maturity of less than one year.13 Often, the short-term bias has been viewed favorably and even encouraged by policymakers. Mexico increased its resort to de facto short-term (dollar-denominated) government debt, the Tesobonos, before the 1995 crisis. South Korea favored short-term borrowings and discriminated against long-term capital inflows. Thailand mortgaged all of its government reserves on forward markets. As documented by Detragiache–Spilimbergo (2001), short debt maturities increase the probability of debt crises, although the causality may, as they argue, flow in the reverse direction (more fragile countries may be forced to borrow at shorter maturities).

Macroeconomic evolution. Despite attempts at sterilizing capital inflows14 in many countries, aggregate demand and asset prices grew. Real estate prices went up substantially.

In contrast with earlier crises, which had usually been preceded by large fiscal deficits, the new ones offered more variation in fiscal matters. While some countries (such as Brazil and Russia) did incur large fiscal deficits, many others, including the Asian countries, had no or small fiscal deficits.

Poor institutional infrastructure. Many crisis countries have been marred by poor governance, low investor protection, connected lending, inefficient bankruptcy laws and enforcement, lack of transparency, and poor application of accounting standards.

Currency regime. As Stan Fischer (testifying to the Meltzer Commission, 2000) notes, all countries that have lately suffered major international crises had fixed exchange rates (or crawling pegs in the case of Indonesia and Korea).

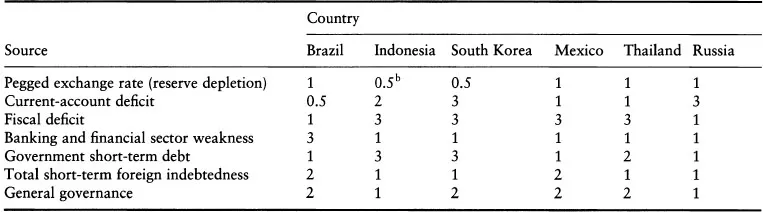

Summers (2000) usefully summarizes the major sources of vulnerability in recent major capital-account crises. As Table 1 shows, traditional determinants of exchange-rate crises (current-account and fiscal deficits) played a role in only some economies. In contrast, banking weaknesses and a short debt maturity seem to have been present in most of the crises.

The crisis

Crises are usually characterized by the following features (in no particular chronological order):

Sudden reversals in net private capital flows. Large reversals of capital flows in a short time interval had a substantial impact on the economies. The reversal reached 12 percent and 6 percent of GDP in Mexico in 1981–3 and 1993–5, respectively, 20 percent in Argentina in 1982–3, and 7 percent in Chile in 1981–3.15 In Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, and Thailand, the combined difference between the 1997 outflows and 1996 inflows equaled $85 bn, or about 10 percent of these countries’ GDPs.

Table 1

Sources of vulnerabilities in recent major capital-accounta

a Notes: Key to table entries: 1, very serious; 2, serious; 3, not central.

b Indonesia let its exchange rate float in August 1998, did exhibit strong signs of real exchange-rate misalignment, and did not expend reserves defending the rate. However, the inflexible exchange-rate regime does seem to have encouraged a large buildup of foreign currency debt in the private sector. (Source: Summers 2000).

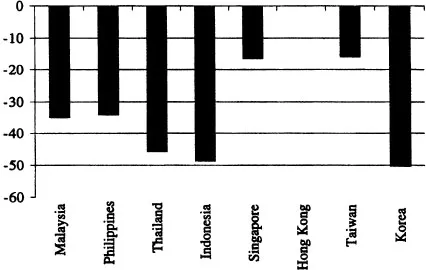

Exchange rate depreciation/devaluation. Most countries suffering a crisis were countries with well-integrated capital accounts and with a fixed exchange rate (or crawling peg). The attacks forced the central banks to abandon the peg or more generally to let their currency depreciate. Figure 1 illustrates this in the case of Asian crises. For example, South Korea’s won lost half of its value in 1997. Thailand devalued by 15 percent and after the IMF got involved the baht lost a further 50 percent. The Mexican peso lost 50 percent of its value in a week in December 1994 before the IMF intervened. The exchange rate depreciation reduced incomes and spending.

Figure 1. Asian exchange rate changes, 1997. US dollar per currency, percentage change, 1 January–31 December. (Source Christoffersen–Errunga 2000)

Activity and asset prices. Bank restructuring proved very costly.16 Fiscal costs associated with bank restructurings averaged 10 percent of GDP and have reached much higher values. Furthermore, whether banks were liquidated or just put on a tighter leash (which was the case for 40 percent of asset holdings in the case of Korean, Malaysian, and Thai banks), restructuring resulted in a credit crunch, which, combined with the firms’ own difficulties, led to severe recessions, in particular in the non-tradable goods sector. Indeed, in Indonesia, Korea, and Thailand, many banks in 1998 not only stopped issuing new loans, but also cut back on trade credit and wor...