![]()

II

The Northeast

Since the eighteenth-century beginnings of the United States, the northeast, as the seat of national wealth, power, population and culture, has more often than not dominated American politics. The exceptions to this hegemony have been periods of popular rule—the Jeffersonian, Jacksonian and New Deal eras—during which Southern, Western and urban working-class upheaval displaced the party of powerful Northeastern interests. More than any other region, the Northeast can be relied upon to defend the politics of the past and the interests of the dominant American “establishment.” Such persisting loyalty produced nationally atypical support for the fading regimes and impetus of John Adams, John Quincy Adams and Herbert Hoover.

In George Washington’s day, the contemporary Northeast—the Middle Atlantic states and New England—was a heterogeneity of regional entities. New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Baltimore were centers of distinctive cultural and economic patterns. The first establishmentarian party, the Federalists, spoke for New England and the Seaboard mercantile aristocracy; they were followed by the Jeffersonians, whose popular politics gave way to a broader grouping of vested interests, only to be overturned in 1828 by the popular Jacksonians. After 1860, a new, powerful Northeastern Establishment of Boston and New York financiers, railroaders, New England manufacturers and Pennsylvania mine-owners and ironmongers, in control of the Republican Party, fought the South and won, profited extraordinarily and set a new course for the nation.

The Northeastern Establishment—those ruling powers which have historically played such an important national role—is not a fixed geographic, sociological, economic or ideological entity; it is a changing aggregation of vested interests, and Northeastern politics have shown a considerable tendency to change in its wake.

After the Civil War, the Northeastern industrial and commercial establishment espoused laissez faire and the locally controlled Republican Party, giving each more support than did any other part of the nation. Finally, the New Deal triumph of 1932 overthrew the old establishment, enthroning a new liberal impetus of expansive government. At first, the New Deal was Western, Southern, urban Catholic and anti-establishment, but as liberalism and the New Deal institutions took firm hold, they gave rise to a new establishment in the Northeast and became vested interests themselves. By 1968, there was a very real Northeastern Establishment centered on the profits of social and welfare spending, the knowledge industry, conglomerate corporatism, dollar internationalism and an interlocking directorate with the like-concerned power structure of political liberalism. Ever the mirror of establishmentarianism, the Northeast of 1968 was the most liberal and Democratic section of the United States (just as it was the most Federalist, anti-Jacksonian and anti-New Deal in bygone days). A new political cycle is beginning, and it is entirely commensurate with past history that loyalty to the existing order of things should be centered in the Northeast.

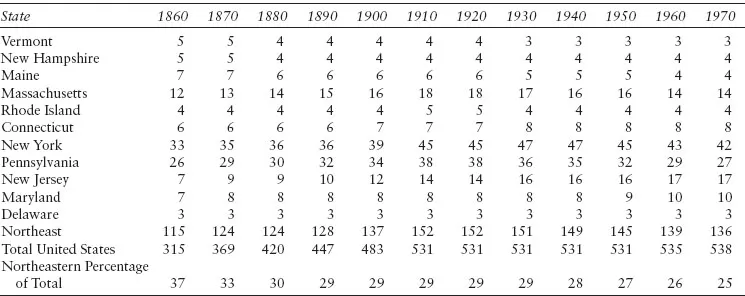

But if Northeastern politics flow onward in a dynamics of establishmentarianism, they do so with steadily less power to sway the nation. Every passing decade has shrunk the Northeast’s share of United States population. Chart 5 shows the steady decline in the percentage of the electoral vote for president cast by the Northeastern states in the century after the Civil War. Liberalism does not face a bright national future as a Northeastern-based establishmentarian impetus.

Chart 5. Northeastern Electoral Vote Strength, 1860–1970, Census Results and Projections

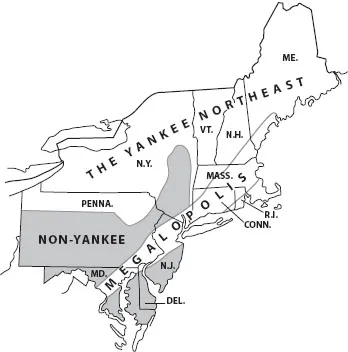

Given the establishmentarianism of the Northeast, it is fitting that the Northeast should be delineated by the Megalopolis, seat of the liberal Establishment. Thus drawn, the Northeast encompasses the eleven states north of the Potomac and east of the Appalachians, all of which save Vermont are traversed by the Megalopolis. As analyzed by geographer Jean Gottman, the Megalopolis is the massive urban-suburban corridor stretching from Washington, D.C. to Portland, Maine.1 It is no exaggeration to say that the Megalopolis is the sociocultural spinal column of the Northeast and the prime shaper of the region’s outlook. Even as the national power of the Northeast is on the wane, the Megalopolis’ share of the population within the region is growing. However, the Megalopolis is not everywhere dominant; part of the Northeast remains small-city and rural. Non-Megalopolitan politics are particularly influential in the six states of Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Delaware, Pennsylvania and Maryland. Prior to the mid-century emergence of the Megalopolis, the true Northeast was more limited in geopolitical scope, pivoting as it did on Northern Civil War tradition.

In the years between the Civil War and the New Deal (and especially between the war and 1896), two different traditions relating back to the fratricidal conflict divided the area now spanned by the Megalopolis. The division was regional rather than sociological. Maryland, Delaware and much of southern New Jersey and Pennsylvania looked to the South while New England, upstate New York and northern Pennsylvania were Yankee by culture and Republican by politics. Map 5 shows the contemporary Megalopolis-defined Northeast, together with the two rural sections of disparate tradition. However, the rise of the Megalopolis has withered the partisan Mason-Dixon line and Megalopolitan social conflicts are structuring a new era. Given the impact of the Megalopolis, the best way to fathom Northeastern political trends is to tear apart the regional political fabric and examine the many strands—rural Yankee, Negro, urban Catholic, silk-stocking and suburban—rather than discuss states or sections. But first a historical sketch is in order.

The Civil War period was a decisive one for the Northeast. For many years the South and the Northeast had been rivals for the nation’s future, and as the two competing socioeconomies moved west, they jealously divided the United States into slave and non-slave spheres of influence. Finally, the peace of Appomattox resolved the issue in favor of Yankeedom. Subsequent decades saw Northern industry expand, Northern capital multiply and Northern interests rule the country through the Republican Party which, having been born in the pre-war sectional struggle and baptized in wartime strife, was virtually an arm of Northern hegemony. By 1929, the laissez faire of Northern industrialism and Republicanism was obsolescent, it was no longer needed for nation-building, but history could not have been written so boldly by a lesser drive.

Throughout this entire period, non-Yankee and non-Republican traditions prevailed through considerable sections of the Northeast; areas that had neither sought the Civil War nor shared in its political and industrial fruits. Most of today’s history books oversimplify the Civil War; the loyalties of the time were quite complex. To many Northerners, the Civil War was a Yankee war, not a Northern war. Not only Border Marylanders and Delawareans, but a sizeable number of Pennsylvania Germans, Southern New Jerseyans, New York Irish, Hudson Valley landed conservatives and Ohio Valley farmers, feeling that none of their own interests were at stake in a war against the South, strongly objected to fighting a war for New England manufacturers and Pennsylvania ironmongers. To some of these groups, the South was their principal trade and produce outlet. For economic reasons, the New England states were the only bloc solidly behind the war. Beyond the boundaries of rabid New England, Northeastern war support was overwhelming only in upstate New York, northern Pennsylvania and the Great Lakes, all areas settled by New Englanders. The Civil War was principally a Yankee war and the party that fought it was principally a Yankee party. As the victors, the Northeast and the Republican party shared the spoils.

Map 5. The Northeast

The non-Yankee Northeast is essentially that part of the Northeast which was settled by non-New Englanders prior to the American Revolution. It included Hudson Valley Dutch, Schoharie Germans, Pennsylvania Germans, Scotch-Irish Appalachian uplanders, Quakers and the Southern-leaning inhabitants of Delaware Bay and Chesapeake Bay. New England is the cradle of the Yankee Northeast, but this latter section also includes most of upstate New York and part of Pennsylvania settled by New Englanders after the Revolution. Almost entirely Anglo-Saxon, the Yankee Northeast was the Nineteenth-Century seedbed of both the Civil War and the Republican Party, while the non-Yankee Northeast viewed both the war and the party with considerably less favor.

Since World War II, a number of Northeastern coastal cities and suburbs have fused into a practically contiguous corridor often called “Megalopolis.” The new sociological oppositions attendant upon the rise of this Megalopolis have blurred the rural cleavage stemming from Civil War traditions and cultural oppositions. Democratic traditions are fading in the non-Yankee Northeast and Republican traditions in the Yankee bastions.

Contrary to public impression, the Civil War did not really create a Republican majority. As a matter of fact, once Northern military-supported Reconstruction governments surrendered their hold on the South, the GOP all but became a minority again, a détente, which persisted through 1896. The base of Republican power was exactly those Yankee districts where Civil War support had been greatest—New England, upstate New York, machine-run Pennsylvania and the Great Lakes. (In Ohio, Indiana and Illinois there were close fights, because Great Lakes Republicanism was counterbalanced by Democratic voting in the Southern-settled Ohio Valley.) Voting patterns tended to refight the Civil War.

In the years between the Civil War and 1896 (when William Jennings Bryan’s agrarian radicalism prompted conservative Democrats to flee to the GOP), Northeastern presidential preference divided along quite predictable lines. Maryland, Delaware and New Jersey—much of southern New Jersey lay below the Mason-Dixon line extended—normally voted for Democratic presidents; Vermont, Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Pennsylvania always voted for the Republican nominee; and New York and Connecticut were highly marginal. In Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Democratic strength occurred in rural and Southern-leaning areas, but from New York north, Democratic support in Yankee country was principally Catholic. Charts 6 and 7 illustrate the presidential partisanship of t...