![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

This book examines the various ways in which economic outcomes differ for women and men and seeks to identify the reasons for these differences. The fact that economic activities differ by gender has traditionally been attributed—only partly correctly—to the advantages of a sexual division of labor. It has been argued that, because women perhaps have an advantage over men in looking after children when they are young, it has been beneficial for both men and women for the former to engage in paid employment while the latter concentrate on (unpaid) housework. But technology, fertility choices, market opportunities, and social norms have changed all of that in the past few decades. Women now have more freedom and more time available for education, for paid employment, and more generally for careers. Yet outcomes in the household and in the market are often markedly worse for them than for men with similar economic qualifications. In this book we seek to understand why this is so, why gender matters in the economic realm.1 We shall see how small differences and relatively minor advantages (such as physical strength for men) can be magnified to produce striking differences in outcomes by gender. These have been translated into economic differences. But, as we shall also see, economics is by no means the sole reason for gender disparities. Socialization, culture, biology, history, and religion have played roles in bringing about gender inequities.

Although the subject matter of this book is extremely important, interest in it among mainstream economists has been surprisingly recent. Only in the past few decades have scholars in economics started addressing these issues systematically. It is not the case that there was no interest at all prior to this. Powerful voices in the past brought attention to important gender issues. Ardent feminists such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Harriet Mill and her husband John Stuart Mill, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony, among many others, sought through their writings to level the gender playing field along many dimensions. But mainstream economists did not follow their cue. However, in recent decades—partly under the influence of feminist economists who have questioned male-centered presumptions in economics—the profession has seriously turned its attention to issues pertaining to gender.

As a result, the literature on gender and its role in economics has been transformed. In the early days of formal analysis in this area, the labor supply activity of women was in the foreground and occupied almost the entire scope of the field. Recently, however, many aspects of women’s economic lives have been investigated, and it has become clear that their labor supply captures only one facet—though a very important one—of their economic well-being. Today the numerous topics pertaining to the economics of gender that are being investigated almost defy classification. Nevertheless, it is possible to organize the research in a manner that communicates the core factors that determine the well-being of women. Furthermore, although it is impossible to present a single overarching model that addresses all the diverse issues, it is possible to communicate the sort of models that are best suited to analyzing them. These, in fact, are the ultimate twin goals of this book.

The problems confronting women in the developed and the developing worlds can be quite different, and so this book treats the core concerns in both. To a certain extent, some of the problems of women in poor countries today are similar to those that were faced by women in the rich countries when those countries were at the corresponding stage of development. However, culture matters, and so does history. Therefore, the lessons learned from the rich countries cannot be directly applied to poor countries. Nevertheless, at a broad level there are some similarities. For eons, the lives of women the world over have been dominated by decisions made by men—by patriarchy, in other words. In the rich countries patriarchy has certainly been retreating for at least a century, though it has hardly vanished. In the poor countries today, the pace of retreat has been much slower. In this book we shall see how crucially important economic opportunities for women are in undermining patriarchy. However, although economic development certainly improves the condition of women, it cannot by itself eliminate the gender differences in outcomes.2

This book is set out in four modules. In the first module (“Fundamental Matters,” comprising Chapters 2 and 3), we deal with core mechanisms—the economic, psychological, and social factors that determine gender differences in behavior. In the second (“Gender in Markets,” Chapters 4–6), we discuss how gender plays out in market activities. In the third (“Marriage and Fertility,” Chapters 7–9), we discuss gender issues pertaining to the economics of marriage and family. And finally, in the last module (“Empowering Women,” Chapters 10 and 11), we discuss what enhances the autonomy of women in their struggle for equality with men. In the rest of this chapter, I outline with a broad brush the sorts of issues that are dealt with in depth in the rest of this book.

When economic outcomes are different for women than for men, not all of these may be due to differences in the constraints they face, the skills they possess, or the discrimination they may encounter. It is conceivable that, in similar circumstances, the economic behavior of women may differ from that of men. For example, in the context of negotiations, Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever (2003) have documented the fact that women, in contrast to men, frequently receive less because they don’t ask for more.3 This can have serious long-term consequences. A lower starting salary would contribute to a substantial wage gap in a few decades even if salaries were to subsequently increase at the same rate. Whether women have different attitudes and behaviors in the economic realm and, if so, whether they respond to the way they are viewed and how this works to their disadvantage, is the subject matter of Chapter 2. In particular, we shall discuss the role of nature and nurture (including socialization) in determining behavior.

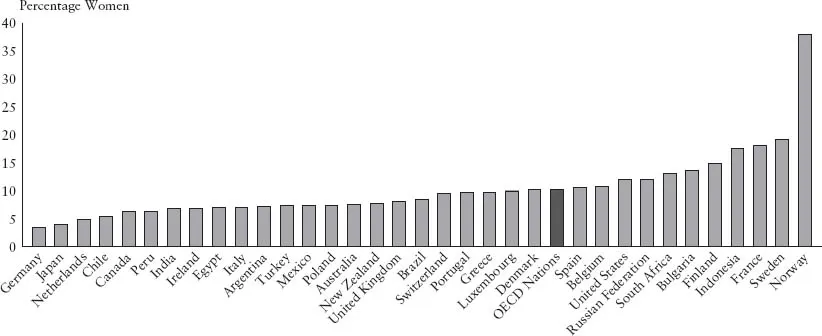

A large part of the gender gap in average wages is due to the fact that, across the world, the top executive positions are occupied mostly by men; relatively few women find their way to the top. See Figure 1.1 for the share of women on the boards of directors of publicly traded companies in the three dozen or so rich countries of the world, which belong to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).4 The OECD average, shown in black (as opposed to gray), is a mere 10%. Norway owes its relatively high proportion of women on boards to legislation that mandated a minimum proportion that is very high by OECD standards.

We would expect that these top positions would be determined by competition among potential candidates based on their past performance. If it turns out that women are averse to this sort of competition, they will stay out of the fray and, naturally, will not be chosen for these positions. If this is the case, women may not make it to the top, not because they lack the skills, the drive, or the creativity but simply because they do not care for the means employed to select the winner. Is this true? In Chapter 2 we shall examine this issue and also survey the experimental evidence on questions of this nature. Furthermore, we shall examine gender differences in competitiveness or cooperativeness, both within single-sex groups and within mixed-sex groups. Interestingly, behavior (especially for women) can differ in the two scenarios and therefore lead to asymmetric economic outcomes.

FIGURE 1.1 Proportion of women on the boards of publicly traded companies in the OECD countries, 2012 (percent)

Source: OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2012), Closing the Gender Gap: Act Now, OECD Publishing, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264179370-en, with permission.

A very important venue in women’s struggle for gender equality is the household. Much of their time and energy are devoted to running their households. But how much say do they have in household decisions relative to their spouses? To what extent can they determine the goods and services on which their households’ income should be spent? Can they single-handedly decide whether they should work in the labor market? And, if they do work outside their homes, how much control can they exercise over their earnings? How much control do they have (if any) over how many children they will have? Do they have any input into how much education their children should receive? Do they have the independence even to decide whether their children need to be taken to the doctor when they are unwell? The answers to some of these questions depend on whether the women in question live in developed countries or in developing ones. And the answers are quite sobering.

The core issue at the root of all of the questions raised in the paragraph above is this: what determines women’s autonomy, independence, or status in their households? This is the subject matter of Chapter 3. The bargaining models used in economics are of great relevance to providing satisfactory answers. We shall first discuss the Nash bargaining model, which identifies the fundamental principle that women’s status in marriage depends on how well they can do for themselves outside marriage.5 We shall examine why this is so. The chapter also discusses why it is that males have the dominant say in marriage in most societies and how the changing outside options of women have been mirrored by their changing status in their households in recent times. In other words, the chapter suggests how patriarchy arises, how it is perpetuated through culture, and how it is undermined. The insights of bargaining theory will be useful in understanding many of the phenomena discussed in this book.

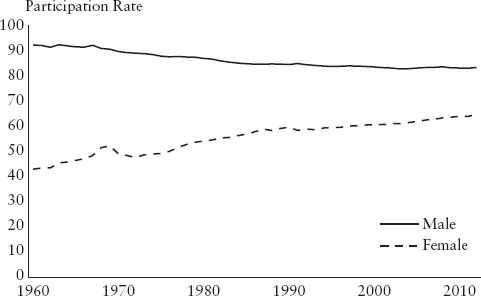

The second module (“Gender in Markets”) examines how gender interacts with markets. Since World War II, the participation of women in the labor market has steadily increased in the rich countries, and that of men has decreased slightly.6 As a result, the gender gap in labor force participation (male minus female participation) has declined, though a gap still exists. The average trends in the OECD countries for the past five decades can be seen in Figure 1.2. There are many reasons that this gender gap in labor force participation has declined. Technological change has reduced the burden of housework and so has freed up the time of women (the traditional homemakers) to work in the labor market. Also, technology has opened up market opportunities for the sort of skills that women are more likely to possess than men.