![]()

1

WHERE POLITICS BEGINS

CICERO’S REPUBLIC

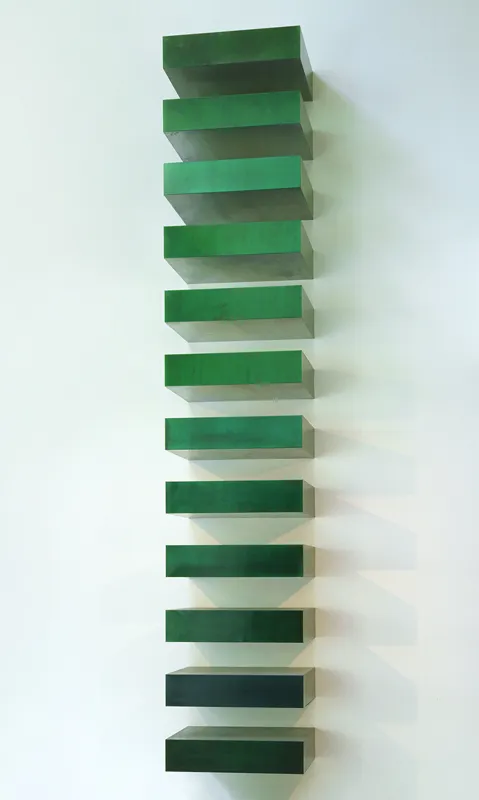

IN HIS FAMOUS 1967 essay “Art and Objecthood” Michael Fried argues that minimalist, or as he calls it, “literalist” art is an art of theatricality; that in its promise of interpretative endlessness—offered by Donald Judd’s boxes in figure 2, for example, which thematize the seriality of return—it fosters solipistic emptyheadedness; and that, banking on its anthropomorphic, dramatically powerful presence, it greets the viewer as a subject and panders to that subjectivity.1 Pieces like Tony Smith’s black-painted steel box and Carl André’s figure-eight stack of rough cedar logs evade art’s primary responsibility and pleasure by dumping the job of creating the art onto the viewer. By contrast, the art Fried favors—Jackson Pollock, Frank Stella, and Anthony Caro, for instance—presents itself in all the glory of its presentness. Proclaiming its identity as art, it transcends the merely theatrical (as Fried would say); it compels the viewer to step out of herself, to contemplate the composition of the piece, to judge the relationship of its various elements, to feel their structural tension, to think in a dialogic relation to the material. The viewer is a free agent, but an agent whose thinking and acting, at least for the moment, takes shape and finds meaning in the space between herself and the composition before her. This relation between viewer and artwork is dynamic but also, in a crucial sense, constrained by the material existence of the composition.

The sensation of composition, of structure, is a theme I will take up again in my discussion of Sallust’s histories in chapter 2. For now, though, I want to single out one concern underlying Fried’s objections to minimalist art in this essay, a concern he pursued often elsewhere in his criticism. “The effect is literally irresistible,” he wrote of Larry Poons’ first show in early 1963, “and it is this characteristic which finally seems to me to limit Poons’ achievement, maybe severely.” Fried glimpsed an “element of coercion” in Poons’ canvases “that runs counter to art, or at any rate to even the barest notion of individual sensibility.”2 Set aside the question of whether or not Fried’s evaluation of Poons is persuasive (I happen to like Poons, so I dis-agree with Fried): the point I want to take away from his discussion is the sensation he describes of being in the presence of the “literally irresistible.”

FIGURE 2 Donald Judd, Untitled (Stack), 1967. Lacquer on galvanized iron, Twelve units, each 9 × 40 × 31”, installed vertically with 9” intervals. Helen Acheson Bequest (by exchange) and gift of Joseph Helman. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA. Art © Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

The specific effect that leads Fried to criticize Poons’ art in these terms is that every viewer of Poons’ work is bound to suffer the optical illusion of the dots’ flickering and flaring under the bright lights of the gallery. The paintings resemble scientific experiments, with Poons the scientist scheming to bring about a specific effect in all his subjects. Poons’ paintings will have this effect on each and every viewer, and the biological design of the human eye means that they cannot escape. This bothers Fried the most: the artist has made a work of art that is designed to push viewers around, to dominate them. Their agency lost, viewers become objects of force.

Fried has more in mind, I think: the viewer of a Poons dots painting confronts a rectangle of canvas covered with paint applied with care (the dots are discrete and of a limited number of colors against a single-color background) but no discernible order or system beyond a roughly even distribution in space. No dot or set of dots draws attention to itself, just as no box in a Judd stack draws attention to itself; the relation of each dot to the other carries no particular hint of a meaning—there are no sites of perceptible tension, no special interaction between the dots and the edge of the piece. The viewer receives no direction: no figuration to concentrate on, no point of energy to start from, no swirls or patterns to follow, scarcely even the trace of the human hand dragging a brush to track. There is energy, but no entry-point. In the case of the Judd boxes, the evocation of the column or the ladder leads in no particular direction. The viewer is suspended; exactly where depends on the viewer—perhaps in the attempt to create meaning, in the enjoyment of symmetry, in the curious search for flaws in the metal. There is no point of focus, no over-balancing or lunge toward an edge—the kind of aesthetic gesture that gives the viewer a place to stand, something to push back against. It is not that the art lacks power, specifically the power to engage: it is simply irresistible.

Fried’s reaction must be understood in the context of his famous (and controversial) view of modernist art, abstract art in particular. He argues that the “chief function of the dialectic of modernism” has been to furnish a “principle” by which painting can be seen and see itself as a tradition, and by which it may transform and renew that tradition. Approvingly citing Merleau-Ponty on fecundity (he has since re-evaluated his heavy reliance on this citation), he sees modern artists as intimately engaged with one another’s work: specifically, as solving formal problems posed by earlier artworks. Fried sees this engagement with other artists, again controversially, in moral terms. Modernist painting may seem to have abandoned lived reality and its material concerns, he concludes, but the “actual dialectic by which it is made”—the relation of artist to artist, work to work—has assumed “more and more of the denseness, structure, and complexity of moral experience—that is, of life itself, but life as few are inclined to live it: in a state of continuous intellectual and moral alertness.”3 To make an artwork that transforms the viewer into an experimental subject who has the same experience as all other subjects, that transforms the idealized dynamic exchange between viewer and artwork into an oppressive act, that reduces the experience of the new into the sensation of having been worked upon: for Fried this breaches the implicit moral code by which he judges modern art.

The themes of coercion and resistibility and the creation of the new are important to this chapter: part of my argument is that it is impossible to discuss republican politics without them. The other part takes up the importance of preserving the conditions of resistibility and novelty in politics. Consider for a moment the political community as a work of art: using Fried’s terms, the community needs to preserve not just the condition of potential disagreement or dissent, but discernible entry-points into disagreement, sites in which dissenting citizens can not only stand but push back and create new ways of thinking and doing politics.

Liberty and concord—agreement on what constitutes the common good—are commonly understood as core republican political values. I argue here for a new approach to these concepts in Cicero’s theoretical writings, mainly his Republic. My aim is not to redefine these two concepts from top to bottom but to examine what his account of both reveals about the conditions of a republican politics.

Three themes will be centrally important and will recur in different ways: 1) the place of the people; 2) the formation of concord and consensus; and 3) the role of aesthetics in Cicero’s conception of the constitution at the republic’s foundation. In the course of handling these, I rebut two common claims: first, that Cicero’s thought holds as the main goal of politics the common good as articulated through a consensus made possible in conditions of concord; and second, that the conditions through which consensus is achieved in this vision confirm the irrelevancy of the Roman political experience for today. Proponents of the latter view either argue that the creation of consensus through public assemblies and the like demanded a high level of active participation in politics that is not sustainable under the conditions of modernity (Benjamin Constant’s point), or they claim that Roman consensus was the creation of a senatorial elite with little or no investment in popular interests.

By putting the practices of Roman politics in a head-to-head comparison with modern politics, both judgments miss the significance of Cicero’s reflections on the republic. Universal freedom and popular participation in politics, by the modern measuring sticks of human rights, ballots, democratic representation, and popular influence on political discourse, are not bedrock values of Roman republican thought, and any attempt to claim otherwise is bound to run into trouble. In its exposure of fundamental tensions at the heart of politics, Cicero’s treatment of liberty and concord prompts us to think about what kind of civic experience we had better value. We will see that matters are more complicated than dismissive judgments of elitism allow: Cicero’s unmistakable bias toward the domination of the senatorial order does not prevent him from illuminating the conditions of political conflict or from identifying practices of politics that may transcend the conventional familiarities of our own postdemocratic moment.4 Chantal Mouffe’s agonistic politics, Andreas Kalyvas’ “politics of the extraordinary,” Jacques Rancière’s notion of dissensus, and Nadia Urbinati’s work on democratic representation are important interlocutors in my account of the Ciceronian vision of politics and how it bears on contemporary experience.

LIBERTY AND CONCORD

In his influential books Republicanism and A Theory of Freedom, Philip Pettit has defended a tradition of political thought he calls “Roman in origin and character” that emerged in tandem with the institutions and practices of fourth through first century BCE Rome.5 Roman writers of this period, Pettit argues, conceived of the freedom of the citizen as that which distinguished the free from the slave: the capacity to live not in potestate domini, not “in the power of a master,” but free from even the possibility of domination by another. Pettit concludes that the three axial “Roman” ideas are the conception of freedom as non-domination, the claim that this sort of freedom requires a body of law under which the polity aims to guarantee the common good, and the belief that institutions are a necessary element in the constitution.

Non-domination involves more than just being free from actual interference by other people at any given moment in time. It means being free from even the possibility of arbitrary interference by others. This is Cicero’s point when he says that “freedom consists not in having a just master, but in having none” (Rep. 2.43). Pettit defends his neo-Roman conception of freedom on the grounds that it captures the breadth and depth of the injustice of various forms of unfreedom, including slavery, better than the liberal definition of freedom as non-interference. The republican theory of freedom as non-domination proposes that slaves are unjustly, unacceptably unfree regardless of whether their masters are in fact benevolent or cruel, because even the slave of a non-interfering master lives according to the master’s arbitrary whim.6 From this paradigmatic example, Pettit expands the ideal of non-domination to a range of other unfree relationships: the worker fearful of losing his job, the wife submissively obeying her dominating husband, the impoverished person subjected to the petty, intrusive supervision of a welfare worker.

Patchen Markell rightly identifies a problem in Philip Pettit’s overarching claims on behalf of non-domination as the heart of the republican account of freedom: that “in seeking to account for the injustice even of rule-bound and norm-governed subordination, we have recourse to a notion of ‘common avowable interest’ understood as the result of a demanding process through which caprice is purified or educated toward universality.”7 Concerned with “the possible unintended consequences of framing an engagement with [imperial power] exclusively around the problem of arbitrary power” (both in the sense of power exercised by whim and without reference to the good of the interferee), Markell suggests that we should concern ourselves not with domination but with the stultifying, “world-narrowing” effect on relations and experience caused by domination that successfully justifies itself with arguments that its interfering action is benevolent—motivated, for example, by the desire to improve or liberate a people. Drawing on the history of European imperialistic interventions around the world, Markell calls this effect “usurpation.”8

I share his concerns about what Pettit’s conception of freedom as non-domination leaves out. With regard to thinking about our Roman sources, however, I see this not so much as a matter of properly defining concepts as it is a problem of understanding where politics begins and in what it consists. In Pettit’s republican polity no one can interfere with another like a master does a slave, and in cases where representatives of institutions, like tax-collectors or army draft officers, must and do interfere, their interference must “track” the people’s “common, recognizable interests.” Pettit himself admits that the belief that consent is a necessary element in the legitimacy of any government “has spawned dubious doctrines of implied or virtual or tacit consent.”9

To avoid such doctrines, he argues that in order to meet the standard of non-arbitrariness, the exercise of a given power (such as tax-collecting) requires neither ongoing participation nor actual consent but “the permanent possibility of effectively contesting it.” Some element of “contestability” is required to stop the imperium of government from coming to represent an insidious form of domination. “T...