![]()

Part I

The Personal and Family Spheres

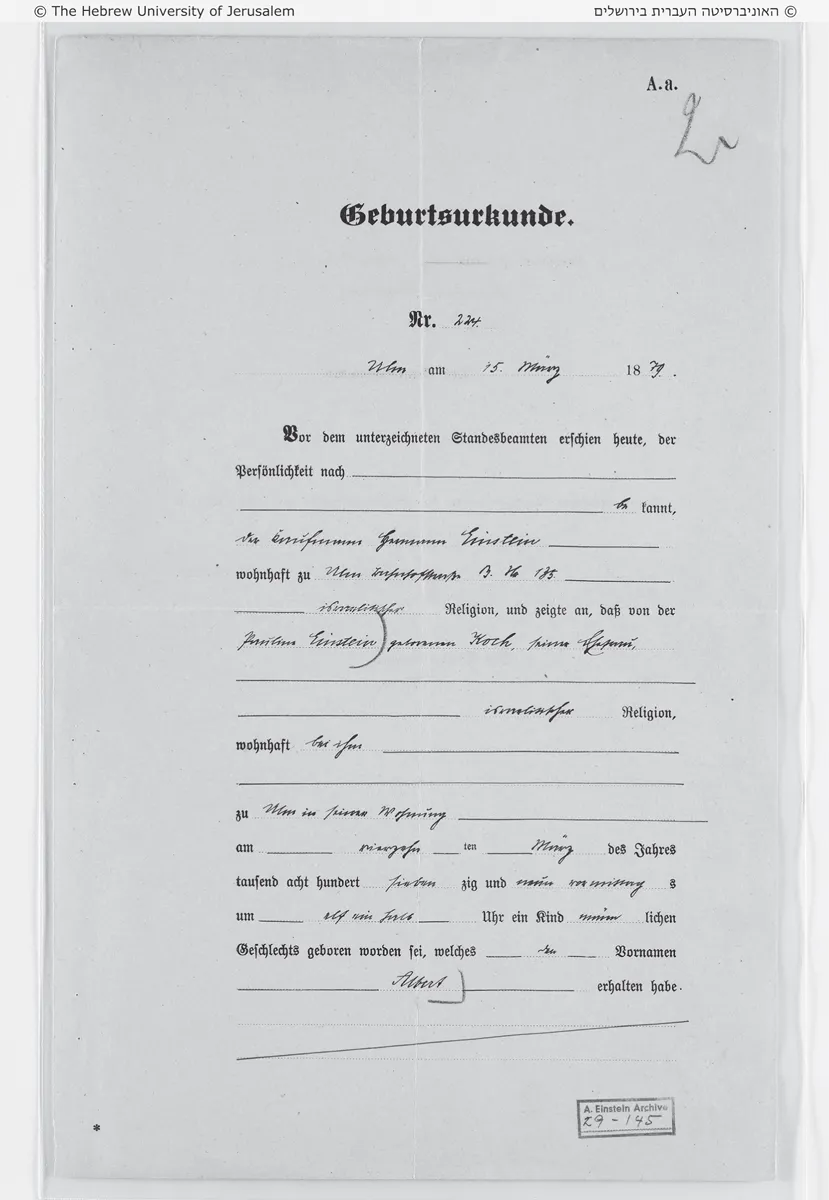

FIGURE 1. Birth certificate. (Courtesy of The Albert Einstein Archives, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel)

Vital Information: Certificates in Facsimile

Below we present samples of important extant facsimile documents relating to Einstein’s life. Translations or further information can be found in the cited cross-references.

Fig. 1. Birth Certificate. See also Birth Information and Family, p. 9

Fig. 2. School Report Card. See also Education and Schools Attended, pp. 28–30

FIGURE 2. School report card. (Courtesy of The Albert Einstein Archives, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel)

Fig. 3. Doctoral Certificate. See also Part II, Doctoral Dissertation

FIGURE 3. Doctoral certificate. (Courtesy of The Albert Einstein Archives, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel)

Fig. 4. Nobel Prize Certificate. See also Part II, Nobel Prize

FIGURE 4. Nobel Prize certificate. (Courtesy of The Albert Einstein Archives, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel)

Fig. 5. U.S. Naturalization Certificate. See also Citizenships and Immigration to the United States, pp. 22–26

FIGURE 5. U.S. Naturalization certificate. (Courtesy of The Albert Einstein Archives, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel)

Fig. 6. Death Certificate. See also Death, pp. 122–132

FIGURE 6. Death certificate. (Courtesy Mercer County Courts)

Birth Information

(As given on Birth Certificate, fig. 1, pp. 2–3)

Date of Birth: March 14, 1879, at 11:30 in the morning, a male child, first name of Albert

Place of Birth: Parents’ apartment, Bahnhofstrasse B, No. 135, Ulm, Württemberg [Germany]

Parents: Pauline née Koch, a homemaker; Hermann Einstein, a merchant

Parents’ Religion: Jewish

Signed by: Hermann Einstein

Archives

(See also Einstein Papers Project and The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, below)

When, in March 1933, Einstein did not return to Germany after the Nazis came to power, his stepdaughter Ilse, with the help of her husband, Rudolf Kayser, and her sister, Margot, packed up his papers in the Berlin residence along with some furniture and other belongings. Rudolf also bundled together some papers at the Einsteins’ summer home in Caputh. Through connections with the French ambassador to Germany, André François-Poncet, the Kaysers were able to remove these portions of Einstein’s literary estate to France via sealed diplomatic pouch. From there they were shipped to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where Einstein took up residence in autumn 1933 (see Fölsing, Albert Einstein, p. 666). These papers and files constituted the earliest form of what later became the Einstein Archives.

In accord with Einstein’s Last Will and Testament (see Death, below), his literary estate was bequeathed to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI). The will stipulated that the files were to be transferred to the university from the Institute after the deaths of Margot Einstein and Helen Dukas (see sec. 13E of the will). Enriched by additional originals, copies, and transcriptions, this literary estate became the foundation of the Einstein Archives.

After Einstein’s death in 1955, Dukas, later with the help of Gerald Holton of Harvard University, began a systematic organization of Einstein’s literary legacy. In the meantime, Otto Nathan, the executor of Einstein’s estate, launched a campaign to acquire new material for the archive, also with the help of Dukas and Holton. One of the goals of their project was to prepare the correspondence, writings, and documents for eventual publication by Princeton University Press (PUP) as The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein. PUP established an advisory board in the 1970s to jumpstart the ambitious project.

After Dukas’s death in early 1982, the archive of original documents was moved to Jerusalem late that year. Dukas had been Einstein’s longtime secretary, and after his death, she had become not only a literary trustee but also the first archivist of his papers. In Jerusalem, the first archivist/curator was Manfred Waserman (1988–1989), followed by Ze’ev Rosenkranz (1989–2003), and Roni Grosz (2004 to the present). The archives were shipped from Princeton to the Jewish National and University Library, administratively a part of the HUJI. They are now administered directly by the HUJI’s Library Authority.

Today the archives consist of approximately 80,000 items, a sharp increase from the 10,000 documents estimated in 1978 and 42,000 estimated in 1980. The 80,000 figure includes not only Einstein’s correspondence, writings, and documents, but also copies, transcriptions, translations, and third-party documents that are invaluable in providing context and preparing annotations. The number also reflects an active and continual search for new materials. As John Stachel, the founding editor of The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, noted in his 1980 guide to the duplicate archive that is now located at Caltech, “The Archive itself is a changing thing. Documents are added and sometimes transferred from one place to another. Annotations may be added, changed, or moved.” Einstein’s diaries, photos, medals, citations, music collection, and books from his personal library are stored in Jerusalem as well, making this the richest of scientific archives.

Duplicate archives for use by scholars have been established at the libraries of Boston University, the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, the Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, and Princeton University in New Jersey. Smaller collections can be accessed in various institutes, colleges, and national archives, to which private parties have donated personal papers that include Einstein correspondence and photographs. Among these are Brandeis University (The Albert Einstein Collection); the Leo Baeck Institute in New York City, particularly useful for its photographs; Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York (Otto Nathan Papers); and the Prussian State Library in Berlin. The Library of Congress in Washington, DC, also has Einstein-related documents and photographs.

Because Helen Dukas and Otto Nathan were the principal figures in establishing the archives, we have placed their biographical information in this section.

Helen Dukas

Helene Dukas, later known as Helen or Helena Dukas, was born on October 17, 1896, in Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, to Leopold and Hannchen Dukas. She was one of seven children. Following the premature death of her mother in 1909, she dropped out of high school to care for her siblings. She later became a kindergarten teacher in Munich and in 1923 moved to Berlin to work as a secretary for a publisher. When the small publishing firm was liquidated five years later, Dukas looked for another job. Her sister Rosa, a friend of Elsa Einstein’s, had heard that Einstein needed a new private secretary because Ilse Einstein, his first full-time secretary, had married Rudolf Kayser and chose to stop working for her stepfather. Rosa alerted Dukas to the open position. After Einstein had employed several temporary secretaries, including Siegfried Jacoby and Edwin Sicradz, Dukas began work in April 1928 as Einstein’s secretary, a position she held until the physicist’s death.

Helen Dukas was not a relative of Einstein’s, but everyone treated her like a family member. She became an enormously important person in Einstein’s life and, after immigrating to the United States, lived in his house with other family members, even after Einstein’s death, for the rest of her life. She never married.

Dukas arrived in Princeton in October 1933 with Einstein and his second wife, Elsa. After Elsa’s death in late 1936, Dukas became housekeeper in the Mercer Street home in addition to carrying out her duties as secretary. On October 1, 1940, she took the American oath of citizenship in nearby Trenton, New Jersey, together with Einstein and his stepdaughter Margot.

Dukas was known for being intelligent, modest, shy, and passionately loyal to Einstein. She was fiercer about protecting his privacy than even Einstein himself. This trait prompted Einstein to nickname her “my Cerberus,” after the hound in Greek and Roman mythology that guarded the entrance to the underworld. Over time, this vigilance and buffering became partly responsible for much of the Einstein mythology. There is no evidence the two ever had a romantic relationship. As if trying to dissuade any rumors, she respectfully referred to him as “Herr Professor” during his lifetime and “the professor” after his death, never as “Albert”—at least in public and in writing. In his last will of 1950, Einstein appointed Dukas, along with his friend Otto Nathan, as co-trustee of his literary estate. The will also stipulated that his personal effects and a sizeable portion of his financial assets be left to her. (See Death, “Last Will and Testament.”)

After Einstein’s death in 1955, Dukas continued to live in the home on Mercer Street with Margot Einstein. She devoted herself to organizing a formal archive of Einstein’s considerable writings and correspondence, a task she undertook first in an office in the basement of Fuld Hall at the Institute and later in a small office on the third floor. She worked faithfully and diligently on the files, adding short notes and cross-references to many of the documents she had filed. Morever, she typed up thousands of transcriptions, mostly of Einstein-authored letters. In addition, she and Einstein’s former assistant Banesh Hoffmann, who became a mathematics professor at Queens College in New York, published two books, Albert Einstein, Creator and Rebel and Einstein, the Human Side.

Dukas continued to come to the office in an Institute shuttle several times a week until her death on February 9, 1982, the result of a ruptured stomach ulcer, at age eighty-five. During her memorial service on February 12 at the Jewish Center in Princeton, Otto Nathan, who had known her for forty-eight years and was close to her for the final twenty-seven, tearfully proclaimed, “When Helen closed her eyes for the last time three days ago, Einstein died a second time. No one was closer to him, no one more dedicated to him. Her purpose in life was to serve Einstein…. She was excited about every new item that came into the archive, as if a part of Einstein himself had returned…. No illustrious scientist could ever duplicate the work she has done.” (From Alice Calaprice’s notes of the service; see also the New York Times’s obituary.) She left her various assets mostly to her sisters and nieces, to Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and to Margot Einstein. She appointed Otto Nathan as the executor of her estate and bequeathed to him a signed, silver-framed photograph of Einstein. (See Einstein Archives 74-628 for a copy of her will.)

Otto Nathan

Otto Nathan was born on July 15, 1893, in Bingen, Germany. An economist, he served as an adviser to the Prussian government during the Weimar Republic from 1920 to 1933 and left Germany after Hitler’s rise to power. After immigrating to the United States, he taught at several universities on the East Coast, including Princeton University, Vassar College, and Howard University, and published two books on Nazi economics. With Heinz Norden, he coauthored Einstein on Peace (1960).

Einstein and Otto Nathan met in Princeton in the mid-1930s, shortly after both established residence there. They quickly developed a trusting friendship that lasted until Einstein’s death. Einstein appointed his old friend as sole executor and a co-trustee of the Einstein estate. With the help of Helen Dukas, Nathan dedicated himself to preserving for posterity Einstein’s established legacy as a secular saint. For years, researchers had tried to construct a more realistic portrait of Einstein but were thwarted by the considerable lengths to which Nathan and Dukas went to avoid sharing information that might be damaging to the physicist’s established reputation. Nathan died in New York City on January 27, 1987, at the age of ninety-three, five years after Dukas. He bequeathed his papers to Vassar College and to HUJI.

Awards, Honorary Degrees, and Honorary Memberships in Foreign Societies

Helen Dukas prepared an incomplete list of awards and honors for the Einstein Archives (Einstein Archives 30-105; see also Reel 65 in the archives). She noted that the citations themselves were left in Germany and that her compilation was likely to be incomplete. However, the archives have since been updated, and we were able to verify all listed honorary degrees with the institutions themselves or with certificates in the archives, thereby adding many previously omitted entries to Dukas...