![]()

1

Entering the Elite

Most Americans believe that hard work—not blue blood—is the key to success. Textbooks, newspapers, and novels are filled with Horatio Alger stories in which an individual rises to the top through personal drive and perseverance. Whether these narratives focus on Warren Buffett or Homeless to Harvard, the underlying message is the same: economic and social positions are achieved, not inherited from one’s parents. The people at the top are there because of their own intellect, unflagging effort, and strong character. Those at the bottom have their own weaknesses to blame.1

Despite this widespread faith in a monetary payoff for hard work and belief in myths of a classless society, economic inequality is now greater in the United States than in many other Western industrialized nations, and American rates of social mobility are lower.2 Contrary to our national lore, the chances of ascending from meager beginnings to affluence or falling from fortune to poverty are slim.3 The top and bottom rungs of America’s economic ladder are particularly sticky; children born to families in the top or bottom fifths of the income distribution tend to stay on those same rungs as adults.4 Children from families at the top of the economic hierarchy monopolize access to good schools, prestigious universities, and high-paying jobs.5

This raises an obvious but pressing question: In an era of merit-based admissions in education and equal opportunity regulations in employment, how is it that this process of elite reproduction occurs? Social scientists in a variety of disciplines have examined how historical and economic changes at home and abroad, social policies, and technological factors have contributed to the concentration of wealth and income at the top of the economic ladder.6 These studies inform us about crucial drivers of economic inequality, but they do not tell us enough about how and why economic privilege is passed on so consistently from one generation to the next.

Sociologists interested in social stratification—the processes that sort individuals into positions that provide unequal levels of material and social rewards—historically have focused on studying poverty rather than affluence. Recently, though, cultural sociologists have turned their attention to the persistence of privilege.7 Focusing on schooling, these scholars have illuminated ways in which affluent and well-educated parents pass along advantages that give their children a competitive edge in the realm of formal education.8 Missing from this rich literature, however, is an in-depth investigation of how elite reproduction takes place after students graduate, when they enter the workforce. We know that even among graduates from the same universities, students from the most elite backgrounds tend to get the highest-paying jobs.9 But how and why does this happen?

To answer this question, I turn to the gatekeepers who govern access to elite jobs and high incomes: employers. Ultimately, getting a job and entering a specific income bracket are contingent on judgments made by employers. The hiring decisions employers make play important roles in shaping individuals’ economic trajectories and influencing broader social inequalities.10 In this book, I investigate hiring processes in some of the nation’s highest-paying entry-level jobs: positions in top-tier investment banks, management consulting firms, and law firms. My analysis draws on interviews with employees of all three firm types, observation of their recruitment events, and in-depth participant observation of a representative firm’s recruiting department. I examine the behind-closed-doors decisions that these employers make as they recruit, evaluate, and select new entry-level employees from the ranks of undergraduate and professional school students; and I show how these decisions help explain why socioeconomically privileged students tend to get the most elite jobs.

I argue that at each stage of the hiring process—from the decision about where to post job advertisements and hold recruitment events to the final selections made by hiring committees—employers use an array of sorting criteria (“screens”) and ways of measuring candidates’ potential (“evaluative metrics”) that are highly correlated with parental income and education. Taken together, these seemingly economically neutral decisions result in a hiring process that filters students based on their parents’ socioeconomic status.

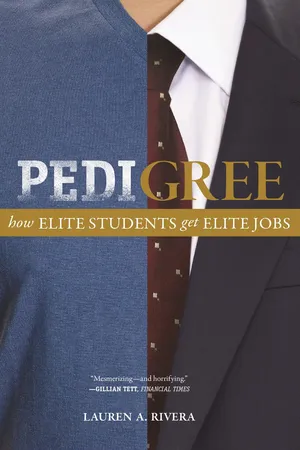

The book’s title, Pedigree, refers to the term that employers in elite firms used as shorthand for a job candidate’s record of accomplishments. “Pedigree” was widely seen as a highly desirable, if not mandatory, applicant trait. Significant personal achievements (such as admission to an elite university, being a varsity athlete at an Ivy League college, or having an early internship at Goldman Sachs) were interpreted as evidence of the applicant’s intelligence, orientation to success, and work ethic. Employers considered pedigree a quality based purely on individual effort and ability. Yet the original meaning of the term, still widely in use today, is synonymous not with effort but rather with inheritance-based privilege, literally meaning “ancestral line.” In that sense, the title evokes the book’s main argument that hiring decisions that appear on the surface to be based only on individual merit are subtly yet powerfully shaped by applicants’ socioeconomic backgrounds. In the twenty-first century, parents’ levels of income and education help determine who works on Wall Street, who works on Main Street, and who reaches the top of the nation’s economic ladder.11

In the remainder of this chapter, I discuss foundational scholarship relevant to elite reproduction in hiring, describe the study I conducted, outline my argument, and provide an overview of the subsequent chapters. I begin by reviewing the literature on socioeconomic inequalities in education. This research is relevant not only because schools shape the pipeline of applicants to jobs but also because this scholarship reveals general mechanisms of social stratification.

ELITE REPRODUCTION VIA EDUCATION

Economic inequalities that occur long before job offers are made help explain how elite kids come to have elite jobs. In prior eras, elite reproduction in the United States commonly took the form of parents handing the reins of companies or family fortunes to their adult children. Today, the transmission of economic privilege from one generation to the next tends to be indirect. It operates largely through the educational system.12

Higher education has become one of the most important vehicles of social stratification and economic inequality in the United States.13 The earnings gulf between those who graduate from high school and those who graduate from college has nearly doubled over the past thirty years. Graduates of four-year colleges and universities typically now make 80 percent more than graduates of high school alone.14

Despite the rapid expansion of higher education over the past fifty years and the popularity of national narratives of “college for all,” children from the nation’s most affluent families still monopolize universities. Roughly 80 percent of individuals born into families in the top quartile of household incomes will obtain bachelor’s degrees, while only about 10 percent of those from the bottom quartile will do so.15 The relationship between family income and attendance is even stronger at selective colleges and universities. In fact, holding constant precollege characteristics associated with achievement, parental income is a powerful predictor of admission to the nation’s most elite universities.16 These trends persist into graduate education, where over half of the students at top-tier business and law schools come from families from the top 10 percent of incomes nationally.17

Many Americans are content to explain these disparities in terms of individual aspirations or abilities alone. But research shows that affluent and educated parents pass on critical economic, social, and cultural advantages to their children that give their kids a leg up in school success as well as the race for college admissions.18 Scholars often refer to these three types of advantages as forms of “capital,” because each can be cashed in for access to valued symbolic and material rewards, such as prestigious jobs and high salaries.19

Economic Advantages

Income, wealth, and other types of economic capital are the most obvious resources that well-off parents can mobilize to procure educational advantages for their children. Simply put, affluent parents have more money to invest in their children’s educational growth and indeed do spend more on it.20 A crucial manner in which economic capital can provide children with educational advantages is through enabling school choice. The United States is one of the few Western industrialized countries where public primary and secondary school funding is based largely on property values within a given region. Consequently, high-quality public schools are disproportionately concentrated in geographic areas where property values are the highest and residents tend to be the most affluent. Families with more money are better able to afford residences in areas that offer high-quality schools and school districts. In fact, for many affluent families with children, school quality is one of the most important factors used to decide where to live.21 Heightened economic resources can also enable parents to send their children to private schools, regardless of the neighborhood in which they reside. In major metropolitan areas, private school tuition can run close to forty thousand dollars per year per child, beginning in kindergarten.22

Together, these patterns make it more likely that children from well-off families will attend primary and secondary schools that have higher per-student spending, better-quality teachers, and more modern and ample learning materials and resources than students from less affluent families. At the secondary school level, children from economically privileged homes are more likely to attend schools with plentiful honors and advanced placement (AP) courses, athletics, art, music, and drama programs; these schools also are likely to have well-staffed college counseling offices.23 Attending schools with such offerings not only enhances students’ cognitive and social development but also helps them build academic and extracurricular profiles that are competitive for college admissions.24 Compounding these advantages, selective college admissions committees give preference to students from schools with strong reputations for academic excellence.25 In short, the primary and secondary schools that children attend play significant roles in whether they will go to college, and if so, to which ones. Students in resource-rich, academically strong schools—which are dominated by affluent families—are more likely to attend four-year universities and selective colleges than are children who attend less well-endowed schools and live in lower-income neighborhoods.

Given the high cost of university tuition, parents’ economic resources influence what colleges (or graduate schools) students apply to and which they ultimately attend. As sociologist Alexandra Walton Radford shows in a recent study of high school valedictorians, many top-achieving students from lower-income families do not apply to prestigious, private, four-year universities because of the high price tags associated with these schools. Illustrating how money and cultural know-how work together, some who would have qualified for generous financial aid packages from these institutions did not apply because they were unaware of such opportunities. Others had difficulty obtaining the extensive documentation required for financial aid applications.26 By contrast, students from affluent families in Radford’s study made their college choices based on noneconomic factors, such as academic or extracurricular offerings, or feelings of personal “fit” with a university or its student body.27

Once on campus, parental financial support can help offset the cost of children’s college tuition and living expenses. Freed from the need for paid employment, students from well-off families can concentrate on academic and social activities and accept unpaid internships, all of which can facilitate college success, valuable social connections, and future employment opportunities.28 Those who have to work part- or full-time to pay tuition bills or to send money to family members do not have this luxury. To summarize, parents with more economic capital can more easily help their children receive better-quality schooling, cultivate the types of academic and extracurricular profiles desired by selective college admissions offices, and participate fully in the life of the college they attend.

Social Connections

Money is only part of the story, however. Social capital—the size, status, and reach of people’s social networks—is important, too. Parents’ social connections can provide their children with access to vital opportunities, information, and resources. For example, parents in the same social network can share information about the best teachers in a school or pass along tips for getting on a principal’s or coach’s good side. Likewise, a well-placed contact can nudge a private school, college, or internship application toward acceptance. Students’ social networks also matter. Having college-oriented friends and peers can shape aspirations, motivate performance, and supply insider tips on how to navigate the college admissions process.29

Cultural Resources

Finally, cul...