![]()

Section 3

THE FUTURE

![]()

CHAPTER 8

The Fate of Fossil Fuel CO2

We would never have imagined life on Earth if we hadn’t seen it for ourselves. The intrepid heroes on the TV show Star Trek occasionally encountered sentient beings composed entirely of energy, rather than carbon. Such beings would never have predicted the magic of carbon on Earth from first principles, or at least from the first principles of science that we have discovered so far.

A tiny fraction of the carbon on Earth is living carbon. If the living carbon on Earth were smeared out over the entire surface of the Earth (a grisly thought) it would be just a few millimeters thick. This thin layer of goo is able to accelerate the chemical reactions on the planet to rates thousands of times faster than they would go otherwise. It controls the chemistry and the climate of the surface of the planet, its atmosphere, oceans, and soils. It aggressively seeks out new chemical reactions to exploit, and has figured out how to harvest light energy from the star the planet is orbiting. Who would have thought of this?

Life is based on the chemistry of the element carbon. No other element rivals it in its complexity on Earth. Carbon’s nearest relative on the periodic table, silicon, has a complicated chemistry on the Earth, too. Silicon chemistry sets the stage for plate tectonics, and the properties of the ocean and continental crusts. The formation of soils as a product of weathering reactions is a result of silicon chemistry.

Silicon controls the Earth’s interior, but carbon has claimed the surface. The carbon cycle extends into the oceans, and into solid parts of the Earth. Trees and grasses are made of carbon, and they leave carbon residues in soils. The ocean contains a thin soup of biological carbon, and much larger amounts of abiological, oxidized carbon in forms like bicarbonate ion, HCO3–. Carbon remnants of dead plankton, from biological tissue and as CaCO3 shells, sink to the sea floor and accumulate in the sediments. Some of that carbon is carried into the deep hot interior of the Earth where the ocean plates converge in subduction zones. Perhaps the largest reservoir of carbon is the sedimentary rocks on continents, deposited there during times of high sea level or tossed from the ocean onto continental crust by the slow train wrecks of plate tectonics.

The atmosphere is one of the smaller reservoirs of carbon on Earth. If the CO2 in the atmosphere were to freeze out into dry ice and fall to the ground in a uniform snowfall around the world, the CO2 snow would only be about 10 cm deep. The large carbon reservoirs in the ocean, on land, and in the rocks, all exchange carbon with the atmosphere. They all breathe, like lungs of different sizes and different breathing rates. The atmosphere is Grand Central Station, a CO2 conduit, shared by all of the CO2 lungs on the planet.

The carbon in fossil fuels has been sleeping in its geological beds for a long time. As it moves into the atmosphere, it will provoke responses from the other parts of the carbon cycle. In some cases the response will be to take up CO2, for example when excess CO2 dissolves in the ocean as described in this chapter. Other carbon reservoirs may tend to release CO2, as in the case of melting hydrates (Chapter 10), amplifying the climate forcing from the original fossil fuel CO2.

Humanity is releasing CO2 to the atmosphere, primarily from fossil fuel combustion, at a rate of about 8.5 billion metric tons of carbon per year. A billion metric tons is called a gigaton and abbreviated Gton. Seven gigatons of carbon is equivalent to 1% of the biomass of the Earth (mostly trees). Our carbon emission outweighs humanity, all the bodies of all the souls on Earth, by a factor of about twenty.

The rate of fossil fuel CO2 release is tiny compared with natural exchanges of carbon between the ocean and the atmosphere. The rates of exchange between the atmosphere and the land biosphere, and between the atmosphere and the ocean, are about 100 Gton C per year, 20 times higher than the rate of fossil fuel CO2 release. It may seem reassuring that humankind is releasing CO2 more slowly than these natural CO2 fluxes. But the fossil fuel CO2 is special because it is essentially new to the fast carbon cycle of the atmosphere, ocean, and land surface. Fossil carbon, slumbering for millions of years, is being injected into the atmosphere, the Grand Central Station of the carbon cycle.

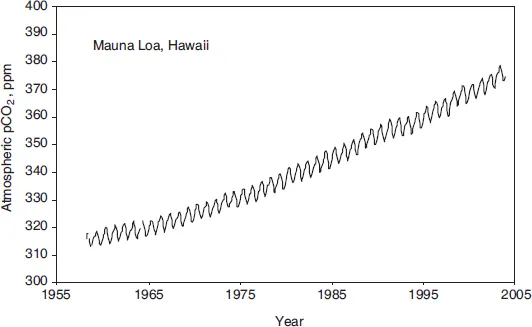

The land biosphere exchanges carbon with the atmosphere. The biosphere on land draws carbon from the air to produce leaves and new branches in the summertime, only to release the carbon again in winter. You can witness the breathing of the terrestrial biosphere in the seasonal cycle of atmospheric CO2 concentration (Figure 13). The northern and southern hemispheres are out of sync with each other, because the seasons are opposite each other across the equator. There is more land in the Northern hemisphere, so the northern hemisphere biosphere breathes more deeply.

The visible carbon—the trees, elephants, people and so on—is made up of about 500 Gtons of carbon, larger than the amount of fossil carbon released so far (300 Gton C), but tiny compared to the total potential amount of fossil carbon available (5000 Gton C). The soil carbon reservoir is larger, about 2000 Gton C, about three times the mass of the living carbon on land but still smaller than the fossil fuel carbon.

FIGURE 13. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations of the past fifty years measured on top of Moana Loa on the big island of Hawai’i. The wiggles are the annual breathing of the biosphere, and the upward trend is caused by human emissions.

The factors that control the amount of carbon on land are complex enough that the land could serve either as a source or a sink of fossil fuel CO2 in the coming century; it is impossible to predict which. Deforestation is already contributing CO2 to the atmosphere, because when trees are cut down, their carbon is ultimately released to the atmosphere when the wood is burned or decomposes. Today this is mostly a tropical phenomenon, because most of the forests in temperate latitudes have already been cut, and may even be regrowing. The rate of carbon release by deforestation is about 2 Gton C per year, a bit less than a third of the fossil fuel CO2 release rate.

There appears to be a net uptake of another 2 Gton C per year into the land biosphere, in places that are not being deforested. For a long time, this huge uptake of carbon was called “the missing sink” because no one was quite sure where the carbon was going. It is difficult to measure the amount of carbon on land, because its distribution, mostly determined by its concentration in soils, is very patchy, so it would take a huge number of measurements to tally the total accurately. Also, unlike trees and elephants, underground carbon cannot be seen with the naked eye, it must be laboriously measured. Even though 2 Gton C per year is an enormous flux, more than ten times the mass of the population of the Earth every year, our ability to see the carbon in the landscape is not good enough to find it.

The best way to determine the fate of the missing carbon is to measure the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, rather than in soils. To simplify the story for the sake of explanation, let’s imagine that the wind blew only from west to east, and that the CO2 concentration in the air just above the land surface decreased steadily from west to east. The atmospheric CO2 measurements would imply that CO2 is invading the land surface as the wind blows through.

In the real world, the winds are not steady but blow in all different directions in the chaotic turbulence of weather. CO2 measurements are made not just at a single pair of locations, once and for all, but every day, from a global network of dozens of locations around the globe. The differences in CO2 concentration around the globe are pretty tiny, and the results of different laboratories have to be calibrated carefully. The CO2 data are analyzed using computer models of the winds, the same sorts of models that predict the weather. These studies commonly conclude that the missing CO2 has gone to ground in the high Northern latitudes, the great northern forests of Canada and Eurasia.

It is not clear where exactly the carbon is going, so neither is it known why it’s going there. It could be that the land takes up new carbon because the growing season is longer in a warming world. Changes in the length of the growing season have been clearly documented in agricultural records. Warming is most intense in high latitudes, explaining why the high latitudes appear to be taking up carbon now.

Alternatively, the land could be taking up carbon because of nitrogen deposition, a by-product of internal combustion engines. At high temperatures in the engines’ power cylinders, nitrogen gas from the atmosphere is converted into a family of nitrogen–oxygen compounds called NOx. These compounds contribute to ozone formation in urban polluted air. The NOx compounds then degrade to nitric acid and rain out, comprising about a third of acid rain. (The rest is sulfuric acid.) The nitrogen then winds up in soils in a chemical form called nitrate (NO3–), which is a plant fertilizer. An increase in the deposition of nitric acid rain might be fertilizing plants to take up the extra carbon.

A third possibility is that higher CO2 concentration itself could be fertilizing the plants. Plants grow better, everything else being equal, in higher CO2 air. Plant growth requires CO2, just as it requires fertilizers like nitrate. CO2 is obtained through vents called stomata in the air-tight waxy seals around leaves. The waxy leaf walls exist to prevent loss of water vapor. Opening the stomata in order to inhale CO2 entails a certain unavoidable loss of water. Higher CO2 concentration in the air enables the leaf to get the CO2 it needs without opening the stomata as much.

CO2 fertilization goes only so far toward stimulating plant growth, however, because plant growth is typically more closely limited by fertilizers like nitrate, rather than by CO2. Forest scientists have made measurements of the CO2 fertilization effect by releasing CO2 into the air upwind of a grove of trees, and then measuring the growth rates relative to the rates of “control” trees that have no extra CO2. Imagine steel towers in a ring like Stonehenge, blowing CO2 on a grove of trees from the upwind direction, 24 hours a day, for years on end. Typically, the trees grow faster for a few years, but then the boost wears off, and the growth rates taper off to normal.

The land surface today just about balances out as a carbon source or sink. Deforestation is almost balanced by high-latitude uptake, formerly known as the missing sink. It is difficult to predict what will happen to the land carbon in the coming century, whether it will be a source or a sink. High latitude uptake of CO2 could continue, or it could taper off as the CO2 fertilization effect saturates (if that is the reason for the present-day uptake). Or the land could start giving off excess carbon, as the bacteria and fungi that decompose organic carbon in soils do their work more quickly as temperatures rise. Tropical soils do not have as much organic carbon as higher latitude soils do, so a transition to a tropical world might in the end reduce the amount of carbon stored in the landscape.

Decisions that people make about how to use the land will have an enormou...