![]()

PART I

Population and the New World

![]()

Chapter 1

Population, Empire, and America

THERE WAS NO ONE ELEMENT WITHIN Thomas Robert Malthus’s principle of population that was wholly new, and yet he managed to make everything about it seem new. He did not invent so much as select from received observations about population and innovate within existing modes of demographic analysis. In intellectual terms, he was a magpie, a thief and reweaver of whatever he stole. That should not diminish his achievement—far from it. His use of familiar features of population analysis, if anything, gave his conclusions added power. But the extent to which he drew upon established modes of inquiry about population, adopting some elements while rejecting others, must be understood in order to appreciate his own and singular contribution: placing new worlds at the heart of population analysis.

Most historians of population studies look too late in the history of the field to make sense of Malthus. In identifying demography as a modern science, they trace its origins to the early modern period, often as late as the eighteenth century, with perhaps a little background on earlier periods. But population had concerned political and religious commentators since ancient times, most notably in Judeo-Christian Scripture. Those traditions of analysis did not cease in the early modern period. Rather, they were overlaid by subsequent and eventually more secular forms of analysis. Because Malthus would draw upon the scriptural and secular, the ancient and the modern, beginning at the beginning of the history of demography (long before it bore that name) is essential to understand his ideas about population and to understand how his contemporaries read them.

Four intellectual strands would be crucial to European comprehension of empires, new worlds, and population, and to Malthus’s own eventual work on these long-connected topics. First, there was a natural theology of human generation, an interpretation of material things and processes that explained them as parts of divine mandate; this natural theology of population stressed that humanity had a genealogy precisely because of Adam and Eve’s fall from grace and expulsion from Eden, a paradise that the new world was sometimes believed to resemble. Second, reason-of-state arguments from the Renaissance presented population as a tool of statecraft, one that was particularly relevant for rulers who had or wanted imperial territories. Third, political arithmetic, the early modern ancestor of demography, used statistical analyses to define knowledge of what populations existed, their sizes, and whether they were rising or declining (and why). Fourth, political economy analyzed modern commercial society in terms of whatever had economic value, including land, commodities, and labor; as such, it depended on a stadial theory of society in which a commercial stage was thought to be the last in a series of ever more sophisticated social forms.

From the discovery of the Americas through the US War for Independence, each of these intellectual idioms would define the new world as particularly important for an emerging, modern science of population. A variety of experts would contribute to each tradition. But even more important, some commentators would synthesize what was familiar in order to generate a new kind of understanding. That was what Malthus would do in relation to the Americas (later the other new worlds of the Pacific), and in this regard he would draw upon the most important synthesizer and theorist before him, the American-born Benjamin Franklin.

* * *

Assessments of the peoples within worlds that Europeans categorized as “new” had taken initial form in relation to the Americas, with a mounting sense that the modern empires located there were qualitatively different from ancient empires, notably Rome’s, and that these new worlds therefore constituted sites of natural experiments in the differential capacity for various populations to utilize natural resources and to increase their numbers, or else fail to do so. Because of this perception of a new quality for the population dynamics of these new worlds, there had also been a serious question of their relation to the story of humanity’s origins as given in Christian Scripture, an emphasis that made especially clear that analysis of population was always an interrogation of the linked qualities of nature and human nature—specifically, of whether there ever could be redemption in the material world.

Natural theology interpreted the material world, including human beings, according to God’s will and divine plan. That plan introduced an important and long-lived trope, the breeding pair. European Christians were aware that the Book of Genesis had commanded a primordial dyad, Eve and Adam, to “increase and multiply,” eventually to “fill the Earth” as part of their divine mandate to exert dominion over nature. Humanity’s scriptural parents heard that admonition while still in Eden, though they would not actually fulfil their duties until they had sinned, were expelled from paradise, and apportioned painful and gender-specific obligations. “In sorrow,” God warned the apple-eating Eve (and her daughters), “thou shalt bring forth children.” Meanwhile, “cursed is the ground for thy sake,” God told Adam: “in the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread,” torn from the ground through daily toil. God would repeat the command to “increase and multiply” to Noah and his family after they survived the Deluge. The sons of Noah were presumed to have repopulated the world after God had drowned Adam and Eve’s other descendants. Exactly which of Noah’s sons had settled in what parts of the world fueled debate, especially the critical question of where Ham (or Cham) had gone after being cursed for looking upon his father’s nakedness. Ham and his descendents were doomed to be the hewers of wood and drawers of water for anyone who could extract such labor from them.1

Scripture had thus provided Christians with a global genealogy, though one that designated human nature as fallen, postlapsarian. The population imaginary that survives even into the twenty-first century, of the fateful impact one breeding pair might have for the entire globe, does not always bear a religious cast, but it definitely did for the Reverend Malthus and his contemporary readers. The original sin of a divinely created pair of humans had ordained that producing children and feeding them would be painful human obligations, equally unlikely (it seemed) to create a surplus either of people or of food. A subsequent set of sins and a punitive deluge had restarted the process of human generation and divided the globe among different lineages described as unequal, some destined to labor for others. The latter point became notorious as justification for the enslavement of sub-Saharan Africans, on the assumption that Ham’s seed, Canaan, had settled in Africa.2

The European discovery of the Americas nevertheless challenged the scriptural explanation of how the Earth had been peopled. As evidence accumulated that the lands Columbus described and explored after 1492 were not, as he claimed, parts of Asia but new worlds entirely, it became difficult to explain how these places had acquired human inhabitants. Which of Noah’s lineages had ventured that far, and why had God not explained them to the Christian faithful, as He had done for all parts of the “old” world? The idea of a separate creation of human beings, polygenism, was technically heretical. Another part of Scripture made that clear: God “hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth, and hath determined the times before appointed, and the bounds of their habitation.” Native Americans had to come from the same stock as Europeans—but how? In some ways, that the primordial breeding pair had dispersed progeny so far away compounded the wonder of human procreation, but the Americas also confounded Christian faith in the idea of a unified human lineage and destiny.3

For that reason, the Americas could be represented either as another Eden, a newly revealed reminder of God’s creative beneficence and possible repository of human innocence, or else as a demonic counterfactual, the long-hidden realm of the devil and ultimate proof of the fallen state of humanity. There would be a rich tradition of associating American Indians with the scriptural past, even with paradise: Columbus was not unique in believing that Eden was located in the lands he had first explored. His descriptions of native Caribs as “guileless,” moreover, set off a long convention of regarding Indians as primordially innocent, living sweetly naked in free-giving natural worlds, as if released from Eve and Adam’s original sin. But equally commonly, the natives of this new world were depicted as Satan’s prey and pawns. Suspicion that the peoples of the new world were cannibals was one of the most powerful of prejudices about them. Their presumed anthropophagy indicated both an inversion of European social norms and a desperate appetite unappeased by American foodstuffs, whether due to natural want or social depravity or both.4

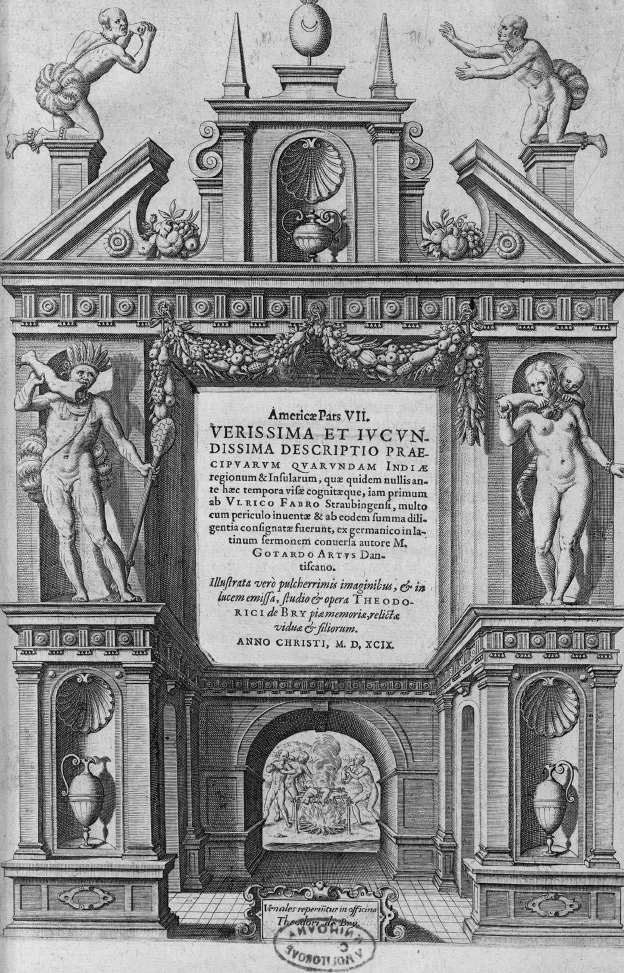

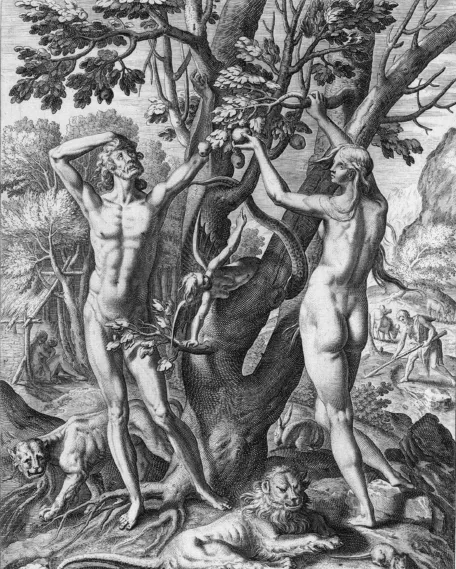

Theodor De Bry’s massive and influential Grands Voyages: Americae (1590–1634), for example, reinforced both interpretations. The frontispiece to the seventh part of this compendium on European reconnaissance of the new world displays the title flanked by an Indian man and woman, each gnawing a severed human body part; an infant tied to the woman’s back reaches hungrily toward his mother’s awful meal. This male-female dyad only reproduces human beings by consuming them, with no net gain. Their postlapsarian state is echoed in another illustration, this within the first part of De Bry’s work, in a portrayal of the Fall and expulsion from paradise. Adam and Eve are in the foreground, just about to taste fruit from the tree of knowledge, and their fallen selves are in the background, performing their divinely mandated tasks. Eve nurses an infant Cain in a primitive hut while Adam scores the ground with a primitive hoe. Through the visual twinning of the two illustrations, the peopling of the world is connected to the peoples of the new world, with Edenic and satanic implications depicted in ironic juxtaposition, a new problem for the Christian faithful.5

All the same, from 1492 and through the seventeenth century at the least, a central principle of natural theology remained in place: God had created a world uniquely suited to its human inhabitants, howsoever many of them there might be. Interpretation of the Americas was important, therefore, in the globalization of that argument from design, a test of Christians’ faith in the idea of plenitude, which Scripture had promised. Although several new world landmasses were still missing from European globes and world maps, the still-expanding extent of South and North America already showed just how much land existed. That raised the question of how fully it might be populated. Were the inhabitants of the new world fulfilling the mandate to increase and multiply, to subdue the Earth? If not, how many more people could fit into their territories, once these were supplied with dutifully procreating European migrants equipped with intensive and commercially oriented forms of agriculture?

Figure 1.1. The new world’s cannibal parents. Theodor de Bry, Grands Voyages, part VII (Frankfurt, 1599). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Figure 1.2. Global parents, Adam and Eve, in new world context. Theodor de Bry, Grands Voyages, part I (Frankfurt, 1590). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

* * *

Before 1500, Europeans typically regarded population growth as a welcome development, if not a moral obligation. Despite recurring premodern fears about food shortages and concomitant sociopolitical instability, these were regarded as local problems. Ghost acres were important to nations or empires precisely as solutions to these localized difficulties. But incipient concepts of the labor value of property stressed that land was useless without people. Dramatic population decline, as with episodes of famine or plague, for that reason threatened the social order. And the larger argument from design and belief in plenitude for the moment held firm: God would not have created a globe inadequate to the terms of his command that humans should endeavor to fill it up.6

Greater fears were expressed about the failure to thrive than about any possibility of overrunning natural resources. Leaders of Protestant nations, including England (later Britain), contrasted their pious fulfillment of the duty to increase and multiply against the Catholics who (the antipapist stereotype went) locked their fertile sons and daughters in monasteries. All the same, Scripture had seemed to warn human rulers that only God should take numerical stock of their peoples: God had punished King David for following Satan’s temptation “to number Israel.” Together, these dictates indicated that sexual reproduction was a divine mandate, so sacred that secular rulers should not involve themselves overmuch in the result. It is notable that Malthus, a clergyman, was to profoundly ignore both these tenets, instead criticizing population increase as documented by censuses that, like King David’s, dared to number the nations. For those innovations, he would be beholden to Renaissance theories about population and the power of states.7

During the sixteenth century, reason-of-state arguments for the benefits of a large population began to augment the religious duty to multiply. According to these political texts, any nation, as a territorial unit, was worthless without population. That almost commonsensical warning was then elaborated as a strategy of statecraft. Traditional reason-of-state arguments stressed static measures of political health, as with steady harvests, production of commercial goods, and maintenance of population, three signs of vigor in the body politic. Through their own personal bodily industry, individual humans generated wealth and revenue for the state. Men filled out armies and navies; women nurtured children who would continue those patriotic tasks in future; all worked to create subsistence and foster commerce. Still, overpopulation was recognized as a problem. Niccolò Machiavelli, not least, warned that overcrowding would eventually weaken a nation, only to be corrected by the natural occurrence of “[in]undations, pestilences, and famines”:

… for nature, as in simple bodies, when there is gatherd together enough superfluous matter, moves many times of it self, and makes a purgation, which is the preservation of that bodie; so it falls out in this mixt body of mankinde, that when all countries are stuffed with inhabitants, that they can neither live there, nor go other where, because all places are already possessed and replenish’d, and when the subtilty and wickedness of man is grown to that fulness it can attain to, it holds with reason, that of force the world be purged by one of these three waies.

It was a dire warning, an indication that competent rulers ought to monitor how extensive their populations were and how fast they might be growing.8

To that end, in his Les Six livres de la République (Six Books of the Commonwealth, 1576), French political philosopher Jean Bodin denied that to take a census was to commit a sin. David had been punished not for numbering his people but for counting his warriors only, omitting the priestly tribes. He had lacked faith in God’s favor to Israel, which required the priesthood. The moral, Bodin argued, was that earthly rulers ought to know their whole populations, with censuses taken as often as they might benefit a commonwealth. Bodin identified another troubling question about populations, ancient or modern: did slaves count? He said yes, slaves were in fact citizens, however inferior ones, an answer that would continue to perplex rulers of composite populations, especially those acquired by means of imperial expansion, as in the Americas.9

Starting with the Jesuit-trained writer Giovanni Botero, reason-of-state arguments stressed not only stability but growth. In his Delle cause della grandezza delle città (On the Causes of the Greatness of Cities) of 1588, Botero launched an important defense of large, dense human populations. Human fecundity was the ultimate source of power: one young couple in Mesopotamia (the presumed site of Eden) had produced all the people in the world, even “to the countries we call the New World.” Against the prevailing assumption that a great nation needed a large territory, Botero countered that “the multitude and number of the inhabitants and their power” mattered far more. The bigger the population, the greater the nation and its concomitant military and economic powers—more people allowed intensive and extensive growth, the former necessary for the latter, an important piece of advice for princes. This was an Italian perspective, by which people from a small but densely populated territory criticized the easy assumption that Spain and France were becoming powerful as national (and global) presences because they had greater territory. The assumption that geographic extent did not mean everything would, likewise, prove attractive to the English, denizens of a small but ambitious nation and later pioneers in population analysis.10

Botero was careful to specify how climate and human customs affected population, two criteria that would continue to be debated well into the modern period. He accepted prevailing environmental descriptions of human populations, distinguishing between hotter and colder climates as preconditions for human health and power. In the end, however, he stressed the significance of natural resources, which attracted people who would turn those resources into wealth, which then continued to attract (and sustain) population. Likewise, he believed that marital customs, and the treatment of women and children, were critical to a state’s fostering of population. He believed that monogamy was the most effective form of marriage—most Christian theorists did—because polygamy denigrated women and their reproductive capa...