![]()

1 | MEDITERRANEAN PASSAGES: RETROSPECT |

I want very much to finish my study of the Mediterranean.… I have infinite longing to see and feel these ancient wonders (my work thirsts for their contact).… The opportunity to continue my search will be of the most profound importance to my work.

—CY TWOMBLY (1955)1

The best witness to the Mediterranean’s age-old past is the sea itself. This has to be said and said again; and the sea has to be seen and seen again.… A moment’s concentration or daydreaming, and that past comes back to life.

—FERNAND BRAUDEL2

IN OCTOBER 1952, funded by a fellowship from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Twombly traveled to Rome and then from Italy to Morocco. Here he rejoined Robert Rauschenberg, who had left Rome earlier to find work in the port city of Casablanca. Together they traveled by bus to Southern Morocco, Marrakesh, and the Atlas Mountains, then north to Tangier, visiting the composer and writer Paul Bowles in Spanish-Moroccan Tetuán at the end of the year.3 During his time in Morocco, Twombly visited the triumphal arches and basilica of North Africa’s best-preserved Roman site, Volubilis; worked on an archeological dig; and made drawings for what became his North African Sketchbook.4 A later (unsuccessful) application for a travel fellowship conveys his sense of unfinished business and his “infinite longing to see and feel these ancient wonders” again. Twombly’s reference to “the land bordering this ancient sea” implies a Braudelian view of the Mediterranean imaginary—a temporal geography at once seen and reseen, imagined and brought back to life.

Reporting on the “wonderful Roman cities” of North Africa to Leslie Cheek, the director of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Twombly wrote:

I’ve learned so much from the Arabs. My painting has changed a great deal. I have hundreds of sketches to use for paintings. Moving so much I haven’t been able to actually paint. I’ve made 6 or 8 large tapestries out of bright material which the natives use for clothing—I plan to use them in my show in Rome next mo.—I can’t begin to say how Africa has affected my work (for the better, I hope).5

Exactly what Twombly learned from “the Arabs” or how French colonial North Africa affected his work (“for the better”) he does not say. Pressure was mounting at the time for Moroccan independence, still three years off. But there is scanty evidence of Twombly’s response to the contemporary political ferment or the tensions caused by Morocco’s rapid modernization.6 Nor does he seem to have been aware of the nascent Moroccan Modernist movement in painting. Still, reorienting him in time and space—“a northerner in the Mediterranean, but more blood and guts”—offers another perspective on his self-proclaimed mediterranité (“I’m a Mediterranean painter”).7 Even before he set out on his travels, Twombly had developed an interest in “primitive” art while studying in New York at the Art Students League, and later at Black Mountain College. He was fascinated by classical and Middle Eastern antiquity, and this trip was the first of many to North Africa and the Middle East. Twombly could not have foreseen how far his thirst for the “ancient wonders” of the Mediterranean would be fulfilled by later travels to North Africa as well as Greece and Asia Minor.8

Bowles would have made an informative guide for Twombly and Rauschenberg when they joined him and his partner, the young magical-surrealist painter Ahmed Yacoubi, in Spanish Tetuán.9 The author of a recent best-selling novel, The Sheltering Sky (1949), Bowles—a veteran of the literary, music, and theater scene of New York—was attuned to the nascent independence movement.10 He was also a gifted travel-writer and ethnomusicologist, keenly interested in Morocco’s traditional musical instruments (including the elusive Riffian Zamar), as well as in its vocal music and dance. He later set out to preserve what was left of Morocco’s musical tradition during the immediately post-Independence period, often in the face of official indifference or outright hostility. His evocative descriptions of the Moroccan landscape in “The Rif, to Music” (1960) and “The Road to Tassemsit” (1963)—offshoots of a Rockefeller-sponsored project to record the indigenous folk music of Morocco’s remote villages in the Rif and Middle Atlas Mountains—provide a glimpse of Twombly’s and Rauschenberg’s travels a decade earlier. Is it a coincidence that a photograph taken by Rauschenberg of Twombly at the window in their Roman pensione shows him strumming on an African bowl lyre?—perhaps a flea-market find, or a Moroccan souvenir.11

Bowles’s travel essay, “The Road to Tassemsit,” contains a litany of Moroccan place-names, along with a vivid description of the landscape through which Twombly and Rauschenberg had traveled by bus:

After Taroudant—Tiznit, Tanout, Tirmi, Tifermit. Great hot dust-colored valleys among the naked mountains, dotted with leafless argan trees as gray as puffs of smoke. Sometimes a dry stream twists among the boulders at the bottom of the valley, and there is a peppering of locust-ravaged date palms whose branches look like the ribs of a broken umbrella. Or hanging to the flank of a mountain a thousand feet below the road is a terraced village, visible only as an abstract design of flat roofs, some the color of the earth of which they are built, and some bright yellow with the corn that is spread out to dry in the sun.

Along with the ubiquitous argan trees, Bowles goes on to describe the arid, inhospitable terrain of the High Atlas Mountains, with their massive boulders, gorges, and fortress houses:

The mountains are vast humps of solid granite, their sides strewn with gigantic boulders; at sunset the black line of their crests is deckle-edged in silhouette against the flaming sky. Seen from a height, the troughs between the heights are like long gray lakes, the only places in the landscape where there is at least a covering of what might pass for loose earth. Above the level surface of this detritus in the valleys rise the smooth expanses of solid rock.12

Along with the stunted gray argan trees and castellated rocks and ravines of the Atlas Mountains, Twombly and Rauschenberg would have seen the dusty earth-colored villages, locust-ravaged date-palms, and prickly cacti of lower altitudes.13

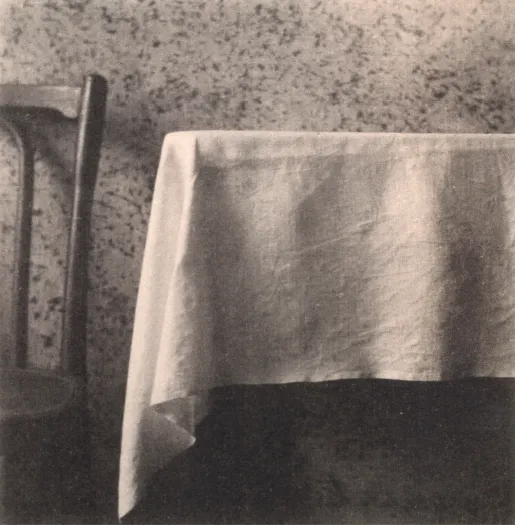

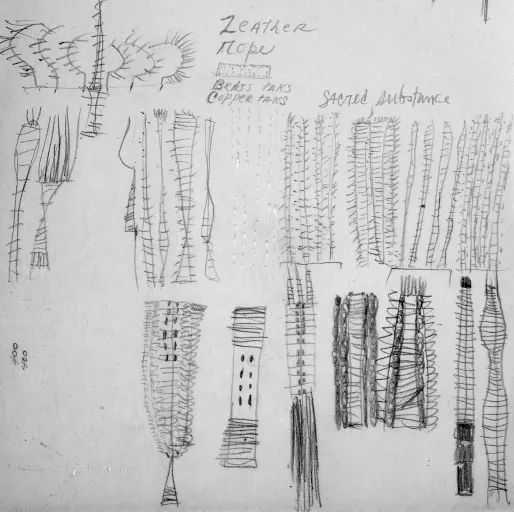

A visual record of the Moroccan trip survives in photographs, as well as in the paintings Twombly completed on his return to New York. Twombly portrayed Rauschenberg in Tetuán, leaning against a hat-stand with a raincoat on his shoulder, like Salvador Dali in his cape.14 He also photographed a tranquil series of meditative still lives: creased tablecloths on a restaurant table—each fold and wrinkle standing out against the mottled wall.15 (See figure 1.1.) A photograph taken by Rauschenberg poses Twombly moodily contemplating the gnarled trunk and thorny branches of a twisted tree (an argan tree, minus the goats?) with a pile of debris in the foreground.16 After his return from Morocco, Twombly completed the thirty-two drawings bound into his North African Sketchbook (dated “Rome, 1953”), a repetitive series of biomorphic shapes in conté crayon on cheap typewriter paper. During the early spring of 1953, he also worked on sketches of sub-Saharan artifacts and African fetishes and phallic objects in the Pigorini Ethnographic Museum, meticulously noting their colors, textures, and materials (nails, rope, leather, brass, tin, feathers, dried grass, and “sacred substance”).17 (See figure 1.2.)

1.1. Cy Twombly, Table, Chair and Cloth, 1952. Tetuán. Photograph. © Fondazione Nicola Del Roscio. Courtesy Archives Fondazione Nicola Del Roscio.

Conditions of travel during 1952–53 precluded painting, Twombly reported to Leslie Cheek. Instead, his travels inspired drawings of abstract, vertically arranged shapes—striated blades, lopsided containers, irregular rhomboids, outlines of obscurely organic tumescent growths that provided a visual language for the paintings and sculptures he made on his return to New York.18 Some of the drawings in the North African Sketchbook include scribbled designs that resemble the knotted and woven objects made by Rauschenberg, combining vegetal shapes with multistranded segments.19 The detailed drawings derived from studying objects in the Pigorini Ethnographic Museum were apparently intended as sketches for sculptures inspired by African artifacts—tied or spiked objects covered in nails; primitive weapons and fertility objects; rows of bristling cones like phallic cacti on legs.20 Meanwhile, Rauschenberg embarked on the hanging constructions he called Feticci Personali, exhibited in Rome and Florence alongside the colorful “tapestries” mentioned in Twombly’s letter to Cheek—wall-hangings with geometrical designs, constructed from Moroccan fabric. Twombly photographed Rauschenberg at work in their hotel room on the assemblages of knotted and looped rope, sticks and bones, tassels and small dangling ornaments (presumably brought back from Morocco) that became Rauschenberg’s tied and woven rope-works.21 Magical and fetishistic significance was interwoven with these objects.

1.2. Cy Twombly, Untitled [North African Sketchbook], XII, detail, 1953. Rome. Pencil on typewriter paper, 8⅝ × 11 in. (22 × 28 cm). Cy Twombly Foundation. © Cy Twombly Foundation. Photo Giorgio Benni.

Rauschenberg, for his part, mischievously posed Twombly, with sketchbook, against the vast disembodied hand of the past (“Cy + relics,” Rome, 1952), and recorded the Capitoline Museum’s collection of antique fragments as a melancholy assemblage of abandoned body-parts.22 (See figure 1.3.) But he was drawn as much to the poverty-stricken detritus of Rome’s post-war flea markets—and perhaps to the indigenous materials in Moroccan street markets—as he was to fragments of antique statuary.23 He had eyes for the ordinary and the overlooked, and for the latent histories of everyday things. His work thrived on “found” objects and improvised materials. For him, “All material has history. All material has its own history built into it.”24 In cont...