![]()

PART I

Duplicity and the Evolution of American Capitalism

They look upon fraud as a greater crime than theft, and therefore seldom fail to punish it with death; for they allege, that care and vigilance, with a very common understanding, may preserve a man’s goods from thieves, but honesty has no defence against superior cunning; and, since it is necessary that there should be a perpetual intercourse of buying and selling, and dealing upon credit, where fraud is permitted and connived at, or has no law to punish it, the honest dealer is always undone, and the knave gets the advantage. I remember, when I was once interceding with the emperor for a criminal who had wronged his master of a great sum of money, which he had received by order and ran away with; and happening to tell his majesty, by way of extenuation, that it was only a breach of trust, the emperor thought it monstrous in me to offer as a defence the greatest aggravation of the crime; and truly I had little to say in return, farther than the common answer, that different nations had different customs; for, I confess, I was heartily ashamed.

Jonathan Swift on the laws and customs of Lilliput,

Gulliver’s Travels (1726)

Corruption, embezzlement, fraud, these are all characteristics which exist everywhere. It is regrettably the way human nature functions, whether we like it or not. What successful economies do is keep it to a minimum. No one has ever eliminated any of that stuff.

Alan Greenspan, interview on Amy Goodman’s

Democracy Now!, Sept. 24, 2007

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Enduring Dilemmas of Antifraud Regulation

In the late fall of 1894, an up-and-coming Midwesterner gained a sharp lesson about the growing reach of the United States government. For eight years, this former railroad station manager had nurtured a succession of mailorder businesses in Chicago and then Minneapolis. Through experiments with national print advertising and wholesale catalogue distribution, he discovered an instinctive knack for mail-order marketing. Cultivating a folksy style, he combined alluring descriptions of goods, aggressive expansion, sharp discounts, and all manner of promotional hullabaloo. Within a few years, he gained endorsements from leading banks and public officials across the Midwest. Farm families responded so vigorously to his engaging sales pitches that his firm struggled to fill the orders that cascaded in with every day’s post. By December 1894, this ambitious thirty-one-year-old employed over one hundred persons and had moved his main operations back to Chicago, to be closer to the manufacturers whose goods he required to meet his obligations. Then, just two weeks before Christmas, the United States Post Office threatened this mercantile impresario with the equivalent of a commercial death sentence. On December 11, the postmaster general issued a fraud order against his firm. The recipient of this administrative notice was Richard W. Sears, the creator of the “Dream Books” that came to rest on hundreds of thousands of kitchen tables across rural America, and the driving force behind Sears, Roebuck & Co. in its first two decades.

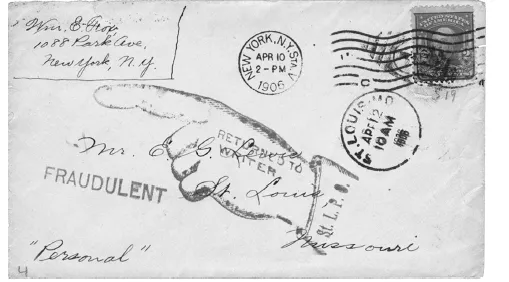

After the issuance of this order, anyone sending the firm correspondence would receive it back with a mark of public shame affixed, like the one in Figure 1.1. The same fate befell any mail sent out by an individual or firm under a fraud order. This administrative sanction represented a far greater commercial peril than civil lawsuits alleging deceptive business practices, or even criminal fraud proceedings, for it threatened to destroy consumer confidence. A fraud order proclaimed that the American state had adjudged a firm’s business practices to be illegitimate. For most mail-order concerns, such a declaration augured crippling losses even if customers’ trust somehow survived the rebuke, because it halted commercial correspondence. As we shall see (and as Sears, Roebuck’s extraordinary growth in the decades after December 1894 would suggest), Richard Sears found a way to make the fraud order go away. But his encounter with postal regulators reflected several interrelated problems that US businesses, policymakers, and citizens have confronted since the advent of modern capitalism—how should Americans define fraud, how much should they worry about it, and how should they structure institutional responses to it?

Figure 1.1: “FRAUDULENT” stamp on a 1906 letter returned to sender because of a postal fraud order. Reproduced with the permission of the Smithsonian National Postal Museum, Washington, DC.

This book retraces how Americans wrestled with these questions for the better part of a century before Richard Sears’s confrontation with the Post Office and for more than a hundred years after it. Throughout those two centuries, Americans of all socioeconomic groups had to navigate the challenges posed by lying promoters and cheating retailers. From generation to generation, the upward swings of the modern business cycle have encouraged investment scams and creative corporate accounting that press at legal and ethical bounds. After the bursting of economic bubbles, journalists, academics, and governmental officials dissect the preconditions for widespread malfeasance in the nation’s commercial and financial firms. In periods of both boom and bust, some enterprises have tried to attract business through misleading or false claims.

Our own generation has confronted several acute episodes of commercial deceit. Millions of individuals have experienced identity theft. The internet has facilitated thousands of marketing scams. Few investors avoided losses from the accounting misrepresentations associated with a string of colossal corporate bankruptcies, such as those of Enron and WorldCom. During and after the global financial meltdown of 2007–08, the business pages chronicled tales of prevarication and corruption at the heart of the American financial system. Deception became endemic within the chain of financing for the residential mortgage market. Manipulation became standard operating procedure in several markets, from the setting of benchmark interest and currency rates to commodities trading to the techniques of high-frequency stock trading.

Some economic deception is, of course, endemic to all modern capitalist societies. Throughout the world, business transactions depend on trust in far-flung counterparties across lengthening divides of space, beyond the social constraints of family, neighborhood, and religious community. The complexity of economic relations has created openings for those firms willing to take advantage of the enduring psychological vulnerabilities that behavioral economists have shown to be common to most investors and consumers. (Chapter Two of this book links the consistent psychological structure of economic deceit to these cognitive and emotional susceptibilities.) As a result, industrialized and industrializing societies on every continent have confronted the problem of how to handle financial and commercial misrepresentation.

Nonetheless, business fraud has occupied a large public footprint in the United States. Many of the world’s most ambitious and expensive frauds have occurred in America; so too have some of the most far-reaching and innovative responses to financial and commercial deceit. From the American Revolution onward, the country’s lionization of entrepreneurial freedom has given aid and comfort to the perpetrators of duplicitous business schemes. Enterprising risk-takers have enjoyed leeway from the arbiters of social norms, the makers of socioeconomic policy, and the practical operation of law, even when enthusiasm encouraged shading the truth or cutting legal corners.

The result has been latitude for processes of economic innovation in the United States, whether based on technological invention, new forms of organization, or the reimagination of the sorts of goods and services that might be offered for sale. But openness to innovation has always meant openness to creative deception. With every technological wonder, with every newfangled financial instrument or mode of organizing business ventures, with every beckoning new market, came bounteous prospects for dissemblers, operators, and downright swindlers. American popular culture, moreover, has retained a soft spot for charismatic grafters and oily-tongued salesmen, evincing admiration for their audacity, ingenuity, and capacity to land on their feet. Social commentators have often paired this appreciation with disapproval of the suckers who proved incapable of resisting pitches that were too good to be true.

And yet, the prevalence of economic deception has also always prompted anxieties about the dangers it posed to the health of American markets, about the possibility that unchecked duplicity might unleash “self-destructive tendencies” in economic life.1 These concerns have generated recurring antifraud campaigns within the American business community, the American state, and the quasi-public domains between the two. American elites, it turns out, have abhorred regulatory vacuums about business fraud, especially at moments in which its social and economic costs have prompted wider public anxieties about the legitimacy of capitalist institutions. Since the early twentieth century, such efforts have been amplified, and sometimes challenged, by antifraud initiatives with more popular roots.

The chapters that follow explore American ambivalence about economic deceit from the early nineteenth century to the present. Since the first years of the American Republic, fraud has posed enduring commercial, political, and legal conundrums. American business owners, investors, consumers, elected officials, jurists, public servants, lawyers, accountants, journalists, and social activists have all tried to resolve dilemmas about how to cope with the problems of commercial and financial diddling, and thus how to constitute key features of capitalist marketplaces. How much freedom should firms have in trying to lure investors to part with their savings, or entice consumers to purchase their goods or services? What sorts of redress should be available if businesses overstep prevailing boundaries, venturing too far away from expectations of candor in their assertions and promises? The perennial issue, whether through common-law adjudication, informal standard-setting, statutory reform, or administrative rule-making, has been how to differentiate illicit chicanery from enthusiastic puffery. Making this distinction has never been easy, either to set overarching policy or guide day-to-day administration and enforcement, as it raises contentious disputes about economic justice and the appropriate boundaries of commercial liberty.

Since the consolidation of independence during the War of 1812, the regulation of American business fraud has gone through four phases. After the two introductory chapters, the four remaining sections of this book grapple with each of these distinctive eras of policymaking and law. For each period, I explore prevailing views about the nature of fraud and the threats that it posed to the commonweal, the emergence of new modes of regulatory governance to cope with those threats, the impacts of those policies, and the critiques that they provoked, which shaped the historical transitions from one era of policy-making to the next.

Part II, “A Nineteenth-Century World of Caveat Emptor,” explores the relationship between antifraud law and business culture from the early nineteenth century into the 1880s. Well after the Civil War, the practical law of business fraud made it difficult to sustain many civil and criminal allegations of deceit. Reflecting a broader ethos of individualism and commercial permissiveness, this legal environment gave economic actors strong incentives to cast skeptical eyes on the firms and individuals with whom they conducted business. It also encouraged robust public discourse about prevalent misrepresentations and swindles, as journalists and editors found strong demand for coverage of business fraud and advice about how to avoid becoming a fraud victim.

Part III, “Professionalization, Moralism, and the Elite Assault on Deception,” explores a series of legal and institutional challenges to caveat emptor that began in the mid-nineteenth century and accelerated in the Progressive era. Calls for greater regulatory paternalism came from many quarters—businessmen seeking to entrench their economic positions; professionals looking to solidify their social standing; social reformers and their political allies in both major parties, who argued that government had a duty to protect many social groups (the aged, the ill-educated and poor, recent immigrants, women, children) who were vulnerable to gross imposition; and individuals from all of these groups who, at some moments, viewed business fraud as a menace to economic and even social order. The resulting coalitions produced a cluster of antifraud initiatives targeting specific markets, such as commodities grading, the marketing of securities, mail-order retailing, and advertising, as well as growing organization of these efforts on a national basis.

Part IV, “The Call for Investor and Consumer Protection,” examines the more ambitious and cohesive assaults on business fraud that policymakers fashioned during the New Deal and in the three decades following World War II. Triggered at first by the enormity of the Great Depression and the ensuing recalibration of government authority, these endeavors moved formal policy toward a stance of caveat venditor—let the seller beware—and relied more heavily on the national government. After 1960, a waxing consumer movement pushed elected officials to impose a yet wider array of disclosure requirements on businesses, and to expand the means by which disgruntled consumers and investors could seek redress through the legal system. Although this expanding web of antifraud regulation fell short of its architects’ aspirations, these policies did circumscribe the scale and societal impact of business fraud.

Part V, “The Market Strikes Back,” traces the partial resurgence of caveat emptor since the mid-1970s, as policymakers became convinced that economic growth required a much lighter regulatory touch. The resulting legal and bureaucratic shifts opened the door for a dramatic expansion in large-scale frauds, committed not just by marginal firms, but by some of the most important corporations in the global economy. It is possible that since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, antifraud regulation in the United States has entered a fifth phase, marked by revived skepticism about the reputational concerns of large corporations and renewed faith in the exercise of governmental power.

Throughout the book, I use fraud as a way to investigate the evolution of business-state relations and regulatory policy. Contemporary discussions of economic regulation often frame it in binary terms—there is “the market,” on the one hand, and the state’s “regulatory bureaucracy,” on the other, with the latter constraining the former in the hopes of redressing some unfortunate byproduct of market activity. But this framing mischaracterizes institutional realities. The efforts of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Americans to deal with the issue of economic misrepresentation show how markets and regulation have always been interconnected. Capitalist production, finance, and exchange depend on complex webs of regulatory policy. From the earliest phases of modern capitalism, regulation has defined property rights and guided contractual relationships by furnishing legal defaults. It has created modes of governance and stipulated social hierarchies for economic units—from the family farm and plantation to the sole proprietorship, partnership, corporation, and holding company, to the cooperative and the labor union. It has set standards for available products and services and demarcated the range of permissible business practices. Law and administrative regulation, in other words, have never stood apart f...